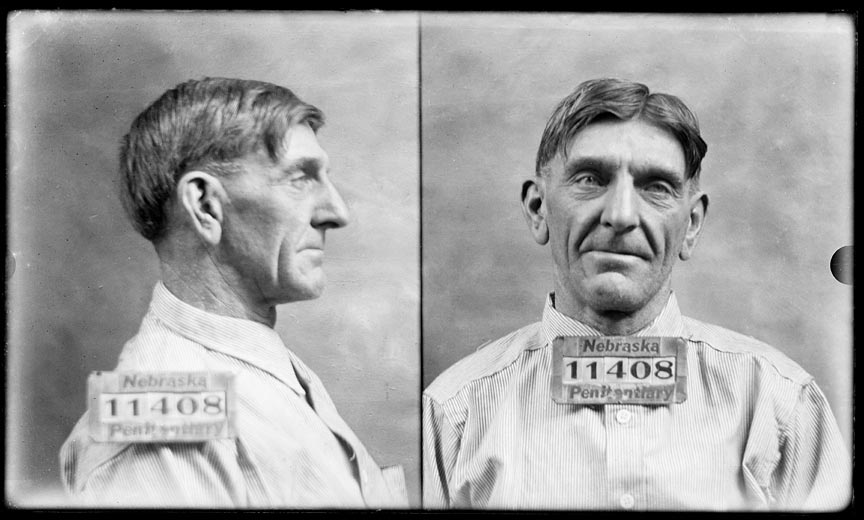

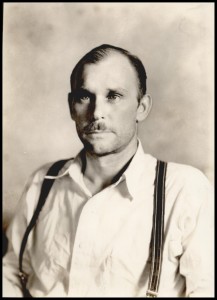

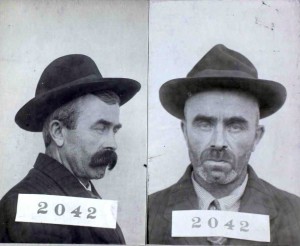

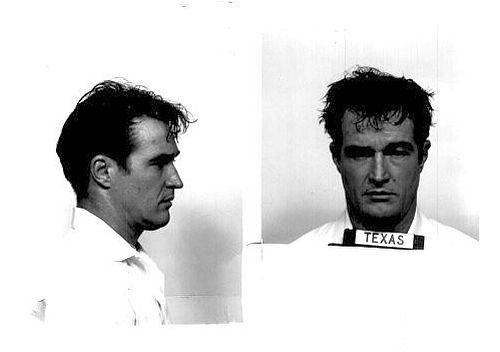

Mug Shot Monday! Thomas Barefoot, 1978

Home | Mug Shot Monday, Short Feature Story | Mug Shot Monday! Thomas Barefoot, 1978

Thomas Barefoot, executed in 1984 for the 1978 murder of Harker Heights, Texas, Police Officer Carl Levin.

.

On August 7, 1978, Harker Heights Police Officer Carl Levin located an arson suspect entering a vacant house in the small community located southeast of Killeen, Texas. When Officer Levin stopped the individual and asked for identification, the man pulled out a .25 caliber pistol and shot the thirty-one-year-old Levin in the head, killing him.

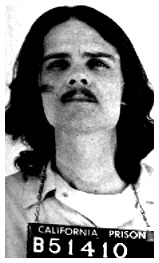

The suspect then escaped the area but was captured two days later at a Houston bus station. A .25 caliber pistol was found on whom they soon identified as Thomas Andrew Barefoot, a thirty-seven-year-old fugitive from New Mexico where he was wanted for raping a three-year-old girl.

Barefoot was hauled back to Bell County, Texas, where he was charged with first-degree murder. During their investigation, local law enforcement learned that two former roommates of Barefoot said he planned to kill a Harker Heights police officer because one of them, not Officer Levin, had roughed him up during a public intoxication arrest on June 6.

In addition to the New Mexico charges, Barefoot had a long criminal history and had served prison time in Louisiana and Oklahoma. His rap sheet shows the Louisiana native had been arrested in the past for aggravated assault, hit and run, lewd molestation, attempted rape, armed robbery, and several other drug and gun charges.

After a three day trial in November 1978, Barefoot was convicted of capital murder and the jury recommended the death sentence.

During his time on Texas death row at the Ellis Unit of the Huntsville prison, Barefoot received stays of execution in 1980, 1981, and twice in 1983. These delays led Barefoot to believe they came from God who was keeping him alive because he was innocent (his claim).

He maintained this strong belief as he and his supporters approached a new and final execution date of October 30, 1984. As they date neared, he “repeatedly said God would intervene and spare his life.”

In the final days, a prison spokesman passed along to reporters Barefoot’s beliefs. “He still experiences hope that a stay will come through. He still talks strongly about religion.”

Before he was led from the Ellis Unit death row to a van that would take him to the death chamber thirteen miles away at the Walls Unit, Barefoot told fellow prisoners not to worry. “I’ll see you later,” he told them. “I’ll be back.”

During the last twenty-four hours of his life, Barefoot was allowed to talk to family members by telephone, visit with family members for ninety-minutes in person, smoke cigarettes, and eat a favored meal of soup with crackers, chili with beans, steamed rice, seasoned mustard greens, hot spice beets and ice tea.

Carl Levin, who left behind a widow, received none of those special considerations.

Shortly after midnight on October 30, Barefoot was strapped to a gurney and allowed to give a final statement in which he lectured Levin’s wife.

“I hope that one day we can look back on the evil that we’re doing right now like the witches we burned at the stake. I want everybody to know that I hold nothing against them. I forgive them all. I hope everybody I’ve done anything to will forgive me. I’ve been praying all day for Carl Levin’s wife to drive the bitterness from her heart because that bitterness that’s in her heart will send her to Hell just as surely as any other sin. I’m sorry for everything I’ve ever done to anybody. I hope they’ll forgive me. Sharon, tell all my friends goodbye. You know who they are: Charles Bass, David Powell…”

Barefoot never said anything after “Powell.” He coughed and then was silent as the lethal chemicals began working.

Carl Levin would have been thirty-seven-years-old when Barefoot was executed. A Harker Heights city park was named in his honor.

—###—

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, November 30th, 2015 under Mug Shot Monday, Short Feature Story.

Tags: 1970s, cop killer, Execution, Texas

Comments: none