The Saga of Mona Wilson: Innocent Woman Serves Ten Years for Murder

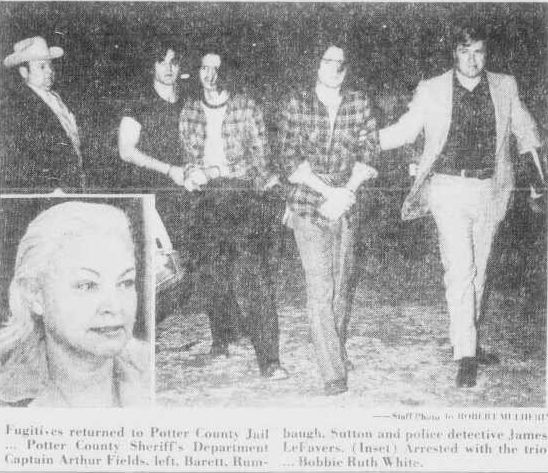

Home | Short Feature Story | The Saga of Mona Wilson: Innocent Woman Serves Ten Years for MurderMona Wilson’s 1927 Mug Shot for the women’s prison in York, Nebraska

In 1927, thirty-one-year-old Mona Wilson lived with her husband of two years on her parents’ farm in rural Sheridan County, Nebraska. She was a loyal daughter who helped them on their rented farm and had little interest in the outside world. Mona and her husband, Herman, lived in a small house on the property while her father and mother, William “Dan” and Olive Loomis lived in a larger home.

On July 16, 1927, Mona Wilson and her parents felt sick and her father sent her to the town doctor, Dr. Albert Molzahn, in Hay Springs, twenty-two miles away from their farm. The doctor wrote a prescription for milk of magnesia and calomel tablets, which Mona then filled at the local pharmacy. She also bought empty capsules to put the medicine in.

Calomel is Mercurous chloride and was used as a purgative and anti-bacterial medicine during the 1800s. In simple terms, it is a mercury-based poison and deadly in large or continuous doses. The deadly effects of calomel on patients were known one-hundred years before Dr. Molzahn prescribed it. Dr. Albert Molzahn was properly educated, graduating medical school from George Washington University in Washington DC circa 1910 to 1912. It is unclear why the doctor was still prescribing calomel in 1927.

Over the night, fifty-nine-year-old Olive Loomis got worse, and in the morning Mona’s father sent her to a neighbor’s house to call for help. By the time the doctor arrived, her mother had already died. Without doing an autopsy, or conducting any tests, Dr. Molzahn declared that Olive Loomis died from strychnine poisoning. A half-empty bottle of strychnine was found in the dresser drawer in Mona’s house, next to the empty capsules she had purchased the day before. This surprised Mona because a full bottle of strychnine was kept in the china cabinet in her father’s home. She claimed she never put the half-empty bottle of strychnine in her own dresser-drawer, and had never used it.

A naïve Mona was arrested and then coerced into a confession with the belief that it would help her husband who was also arrested—even though he was in another part of the county when his mother-in-law died. Her guilty plea led to a thirty year sentence which was later overturned and a new trial ordered. During that second trial, her defense attorney arguing Mona Wilson was mentally deranged because, in part, she had epileptic seizures. The jury found her guilty and sentenced her to life in prison. The state supreme court upheld this decision.

It is unclear how the doctor concluded so quickly, and without testing, that Olive Loomis died from strychnine poisoning. Her husband, “Dan,” who also said he was sick from the poisoning but managed to recover, blamed Mona’s husband, Herman, whom he loathed. He also despised his daughter for marrying him. When Dr. Molzahn arrived that morning to find Olive Loomis dead, Dan loudly accused his son-in-law. This led to a search of Mona and Herman’s home, where the strychnine tablets were conveniently located. These same strychnine tablets had been purchased years before to poison squirrels, and were kept in her parents’ china cabinet in their house.

A year or two after his wife died, William “Dan” Loomis married a twenty-year-old woman (Ida Adams) when he was sixty-years-old. He was never investigated as a possible suspect in his wife’s death. The police only considered Mona and her husband, Herman, who was not even on the farm that day. He had found work on a farm in another part of the remote, rural county.

Since no autopsy was performed, it could never be determined if Olive Loomis did die from strychnine poisoning, or if she died from the mercury chloride.

The following article was published one month before Mona Wilson’s parole hearing in 1937 which took place at the women’s prison in York, Nebraska. By then, she had served ten years for the death of her mother whom she swore she did not poison.

Tells a Complicated Story of Death by Poison – Strange Farm Killing in 1927 May Not be Woman’s Crime – February 15, 1937, edition of The Lincoln Star, page 12.

There are people who would tell you as they have told the board of pardons that Mona Loomis Wilson is not guilty of murder. They would tell you that the state has held her for ten years for a crime she did not commit.

They would tell you that Mona Loomis as a child was a good girl, that she would not have killed anyone—least of all her mother; that she was a good wife to Herman Wilson, more than faithful to admit a crime she did not do when told he had “spilled enough” to send him to the chair. She probably would tell you that herself.

Hers is one of the twenty-six women the parole board will hear when it meets March 10, 1937. It is one of those crimes which unfolds like a detective story you read for fun. But a jury sent Mona Wilson to prison for life.

Mona Wilson’s story will take you back to the summer of 1927, to a Sheridan county farm near Marple (Nebraska). There, she lived with her husband in a tiny house in the same farmyard with the larger home of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. William ‘Dan’ Loomis.

One July Day.

One July day, Don Loomis and Herman Wilson had words. Afterward Herman told his 31-year-old wife he was going to “hire out” as a “hand,” and maybe he would rent a farm and then he and Mona could move away from the home place.

Herman Wilson did hire out and Mona lived with her parents but she didn’t forsake the tiny house she and Herman had—she slept there. July 16, 1927 was a Saturday and in that night Mona and her parents were taken sick. “I felt well enough the next morning,” Mrs. Wilson relates, “to go out and milk the cows.” When she came back to the house from this task, Dan Loomis told her to go to town and have the “doc” send something out.

Events came in quick succession after that. She drove to town, saw the doctor at his house. The doctor telephoned a prescription to the drug store and Mrs. Wilson drove there to get it. “The boy who filled the prescription,” she states (in her parole application), “was not a registered pharmacist.”

She maintains she bought empty capsules from “the drug store boy,” to fill with the medicine the doctor had prescribed. Back at the farm, she and her parents all took several doses of the medicine, she says. That night Mrs. Wilson went to her house to sleep.

Mrs. Loomis Dies

“It was hot,” she declares, “and I heard father when he called—the doors were all open.” He told her to go to the nearest neighbors for help, telephone for a doctor—that her mother was worse.

She did. The neighbors returned with her. Mrs. Loomis died before the doctor arrived. When the doctor came, he wanted to see the capsules.

“Father said they were in a candy sack on the dresser.” Mrs. Wilson says. “But nothing of the kind was ever found.”

“It was decided mother died from strychnine poisoning. My father insisted my husband was to blame for it.”

“The empty capsules I had bought I took home and put in my dresser drawer. There was a full, unopened bottle of strychnine on the [property]. It was kept in the china closet in the house occupied by my father and mother. I had bought two bottles about two years before to poison ground squirrels and only used one bottle. The one in the house was the other bottle.

Strychnine Found

“When the officers searched our house they found a part of a bottle of strychnine in my dresser drawer with the empty capsules. The full bottle was gone from the china closet in my parents’ house.” Mrs. Wilson goes on to explain that her husband had written that he would be home on that eventful Sunday. When she went [to the doctor and to the pharmacy] she left a note on the table in her house telling [her husband] where she was.

“They found the note as I left it,” she states. “With what father had told them and that note, they thought he (Herman, her husband) had something to do with mother’s death so on the morning of July 19, he and I were arrested.”

Mrs. Wilson was taken to a private hospital in Hay Springs. Herman was placed in the Rushville jail. She relates how officers were to take her to her mother’s funeral, but “waited to get there just after the funeral was over.”

Later, officers told her, she declares, “my husband had told them enough to send him to the electric chair. I had always been taught to believe the officers were always fair, so I never once thought that one of them would lie to me in an effort to make me tell what they wanted me to.”

Sites A Confession

Because she thought her husband innocent, Mrs. Wilson says she ordered the county attorney to draw “any kind of a confession he wanted so long as he left my husband out of it and I would sign it.”

Pleading guilty, she was sentenced to 30 years but the state supreme court ordered that the case had to tried before a jury. It took two years for this procedure—two prison years.

Attributing her conviction to the confession, Mrs. Wilson adds “I realize all this looks very bad for me but I really don’t know how it happened. I can only say my mother was my best friend on earth, that she was always very good to me, and I loved her as well as anyone loves their mother.”

Is Trusted Inmate

During the years which have crept by, Mrs. Wilson has become one of the trusted inmates of the York reformatory. She superintends the dairy farm there. She has charge of the visitors’ gate. Officials at the reformatory recommend her (for parole). One such letter to the board said. “I have never found it in my heart to believe her guilty.”

Her closer friends are stronger than that in their letters regarding the case.

Should the board release Mrs. Wilson. Herman Wilson will take her to his Elmwood home. Reformatory attaches say he has visited her frequently during the ten years.

Epilogue

Mona M. Wilson was paroled that spring. The 1940 US Census shows that Mona, 44, was still married to her husband Herman, 57, and they lived in Lincoln, the state capital. She worked as a maid and he worked as a house painter. Herman died in 1964 and Mona died in 1980. They are buried at Ash Hollow Cemetery, (a pioneer cemetery that is one of the most famous cemeteries in the state), in Garden County near Lewellen, Nebraska.

William Loomis married a twenty-year-old woman (Ida Adams) in 1928 or 1929, when he was sixty-years-old. His father-in-law was four years younger than he was. The 1930 census shows they all lived together in Elm Grove, Kansas. In 1940, the couple were living in Box Butte County, adjacent to Sheridan County, in Nebraska. At that time, William was seventy-one-years-old, and his wife, Ida, was twenty-eight-years-old. They had a four-month old daughter, Delores Ann. William Loomis died in 1958 at the age of ninety. Ida remarried Lyle Zimmerman in South Dakota in 1977. She died in 1992.

A poem written in 1825 warning doctors about calomel.

Since Calomel’s become their boast,

How many patients have they lost,

How many thousands they make ill,

Of poison, with their calomel.

—-###—-

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, February 24th, 2016 under Short Feature Story.

Tags: 1920s, Injustice, Nebraska, Women

Comments: none