UPDATE TO THIS STORY:

An important update to this story announced on August 5, 2020, is posted at the end of the article.

– – – # # # – – –

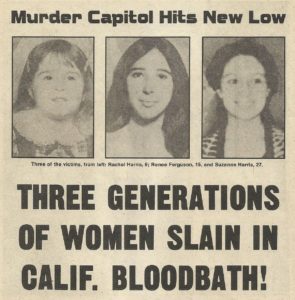

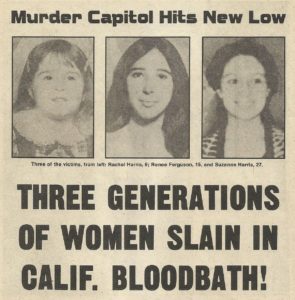

Four Females Slaughtered to Protect Underage ‘Love’ Affair

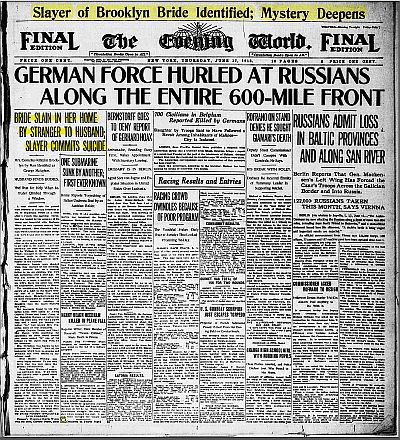

A 1978 crime magazine article highlights the gravity of the crime with a bold headline.

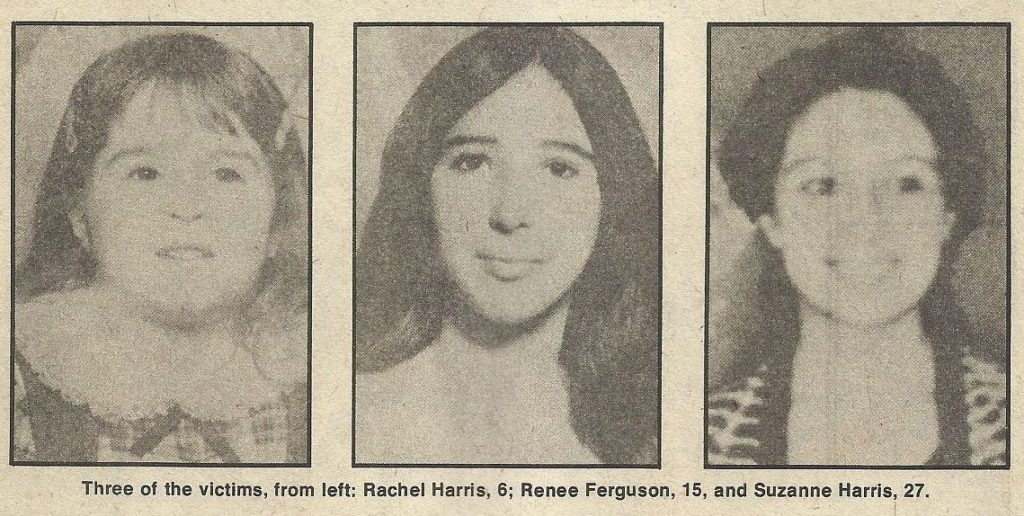

On the morning of August 11, 1977, a Seaside, California, police officer kicked down the door to a small duplex and found four females spanning three generations of the Smith family dead from too many stab wounds to count.

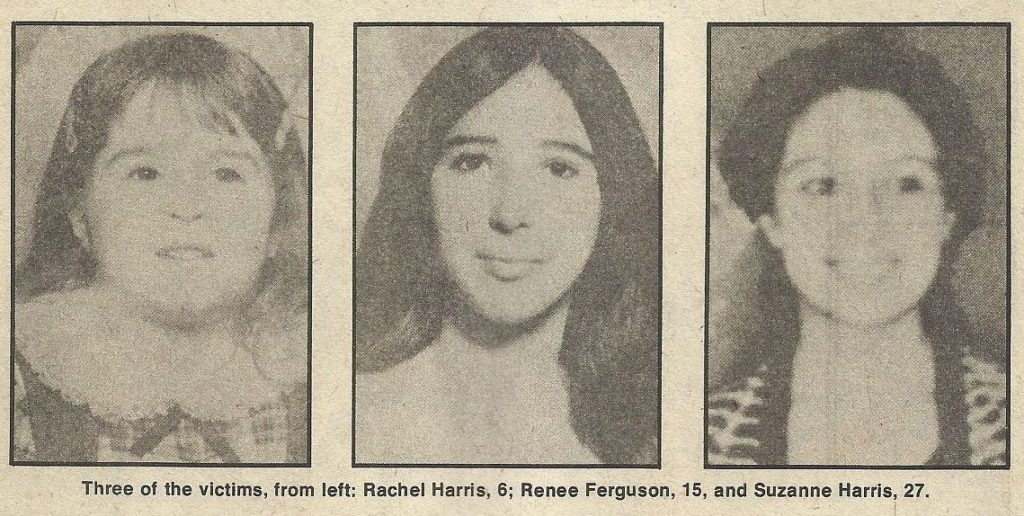

Looking into the kitchen, he could see Josephine Smith, the white-haired grandmother, lying dead next to her twenty-seven-year-old daughter, Suzanne Harris, who was lying dead next to her six-year-old daughter, Rachel Harris. In the bedroom, Renee Ferguson, another fifteen-year-old Smith family granddaughter and niece to Suzanne, was found dead, lying across the bed with her hands tied behind her back.

All four females had not been seen since attending church on Tuesday night, August 9. After the service, Grandma Smith promised the Assembly of God Church pastor they would return the following evening for his evangelical seminar. They never came. It wasn’t like Grandma Smith not to appear when she said she would. He thought about checking on them, but his attention was directed elsewhere.

That Wednesday morning, both Suzanne Harris and Renee Ferguson were supposed to be at work; Suzanne at an electrical firm, and Renee to her summer job she had gotten through the youth job corp. Neither one of them showed-up and Suzanne’s car remained under the carport, exactly where it had been parked the night before.

Later that Wednesday night, a friend of Renee’s mother asked a neighbor acquainted with the family to check on them the following morning when he went to work. At 5:30 a.m. that Thursday, August 11, no one answered the front door, but as he was walking away, he noticed a light on in the bedroom, peered through the window, and saw Renee face down on a blood-soaked bed with her hands tied behind her back. Approximately ten minutes later, the officer was kicking down the door to the worst crime scene of his career.

Inside the home, detectives found a house of human slaughter that looked like something out a low-budget, teenage slasher film—the kind targeted for young people eager for an emotional thrill.

Inside the home, detectives found a house of human slaughter that looked like something out a low-budget, teenage slasher film—the kind targeted for young people eager for an emotional thrill.

An autopsy later showed that each victim had been stabbed between nineteen and forty-five times. The wounds were made with a knife so long that almost all of them would have been fatal. Even with three victims lying clustered together on a linoleum kitchen floor, every surface inside the small residence seemed untouched by gore.

Grandmother

Josephine Smith

“I walked in and saw blood all over and the officer told me to get out,” the neighbor later told reporters. “I don’t ever want to see anything like that ever again. It about made me sick.”

They may have found a lot of blood, but it was what they didn’t find that would cause the investigation to last far longer than anyone in the community could stomach.

The windows and door were not broken.

There didn’t appear to be a struggle inside the home.

None of the victims were sexually assaulted.

Nothing valuable was taken from the home or from any of the victims.

In short, there were no clues, no suspects, and no motive.

But what they did have was a hell of a lot of blood. And down in that blood, they would later find foot prints that were only visible in a crime scene photograph. After careful study, they concluded there was one large shoe print, and another print, not as big, maybe a bare foot, but it was small. Who did that belong to? Rachel?

Although inexperienced with investigating a house full of dead women, murdered by some movie theater monster with an unseen-face, a long-knife, and a short-temper, the Seaside police force used every resource available to them. Their investigation was thorough and professional. They did what they were supposed to do. They interviewed everybody that knew the family. Twice. They interviewed 500 people before it was over. They searched for clues within a wide radius of the area. They investigated every tip and lead that came into a special hotline. They sent out bulletins and called in reinforcements from the state Bureau of Investigation.

But when the crime wasn’t solved fast enough, the fear of Seaside residents turned to anger and resentment against their own police force. Serving a community of just 23,000 people, they thought the force was too small for the kind of mass-murder that should have happened somewhere else.

After the bodies were discovered, they organized citizen brigades to patrol the streets on foot. Volunteers with CB radios cruised the back roads all-night in their vehicles, talking to each other in official sounding language about all clear this and suspicious looking that.

At the end of three weeks, they grew tired of playing cops and movie monster killers. Without a suspect in custody, the family members complained to the mayor and the media. Then, the media started asking loaded questions about the investigation being led by just three detectives on the Seaside police force.

The lack of trust by the public got so bad that the California Department of Justice had to investigate the investigation. Released on September 19, their evaluation asserted the performance of Seaside detectives “is complete and being conducted competently.” It further stated that no involvement by the state DOJ was necessary.

In short, the local police were doing their job and just needed a break in the case.

The break in the case came from an anonymous nineteen-year-old girl who called into a hotline to give them the name of the killer’s new girlfriend. The caller was the ex-girlfriend, and she was calling about getting her replacement arrested. Her name was Terrie Milligan, 14, and she was pregnant with the killer’s baby.

When they asked who he was, she scoffed out her surprise they weren’t hip to who the killer was.

She had to tell them: his name was Harold Arnold Bicknell. Except, she didn’t say it in a normal way, she spit it out of her mouth with sarcasm and ridicule wrapped around it.

“And who is Harold Bicknell?” the detective asked the caller.

“You don’t even know that?” she snapped. “I thought you said you were a detective investigating those murders.”

Harold Bicknell was the nineteen-year-old grandson of Josephine Smith; nephew to Suzanne; cousin to both Rachel and Renee; the Harold Arnold Bicknell who sang in the church choir and volunteered for the citizen patrol for one day; the same Harold Bicknell who joined the Navy two days after the murder. And the same Harold Bicknell who had a fourteen-year-old girlfriend that replaced her, the girl on the telephone, who was really calling to get her rival in trouble.

The movie that had ended as a teenager slasher film began as a teenage love-triangle for the plot.

The detective who took the call investigated Harold Arnold Bicknell by questioning his friends. Those who knew something, talked.

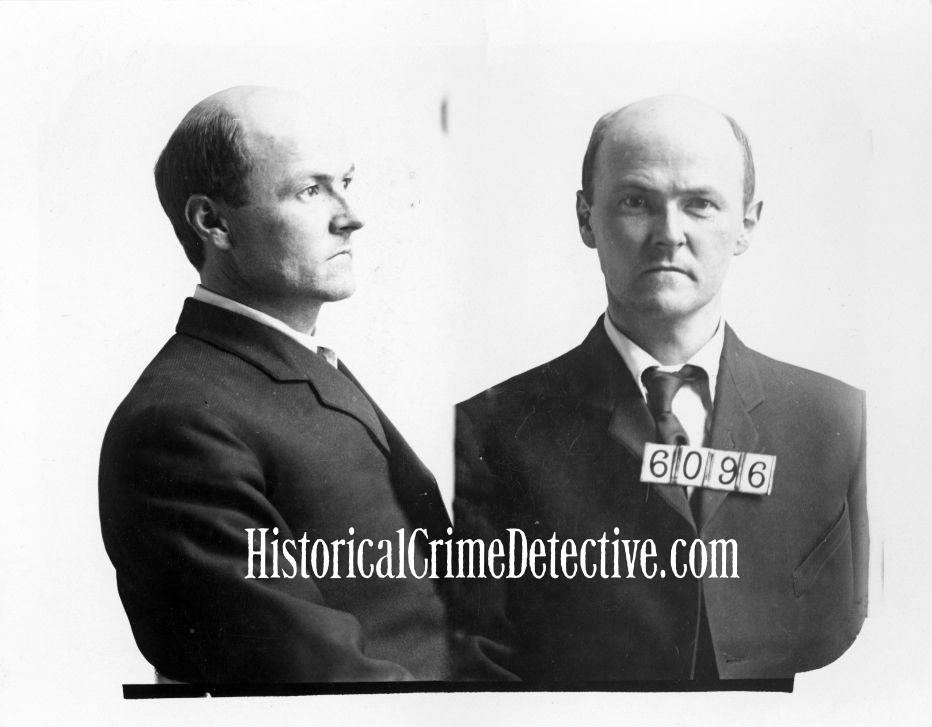

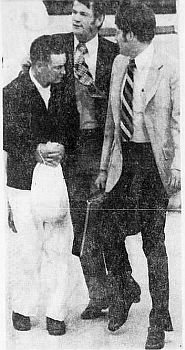

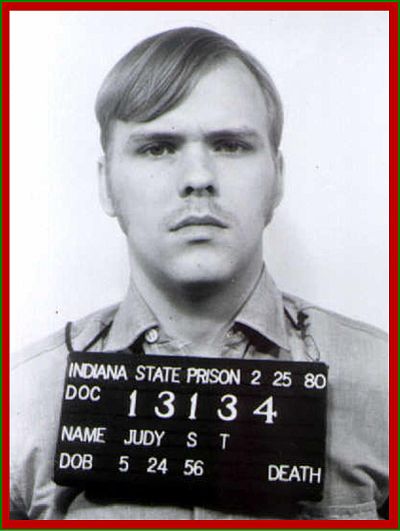

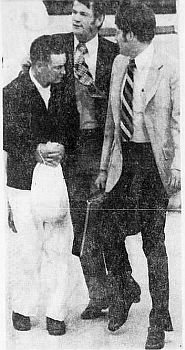

Bicknell is escorted off the plane that brought him back to Monterrey County.

On October 26, Bicknell was arrested at the San Diego Naval Training Center and brought back to Monterrey County. He later made a partial confession to the crime on tape. His fourteen-year-old girlfriend, Terri Marie Milligan, was also arrested and charged as a juvenile for her involvement in the murders. In late November, another young girl, fifteen-year-old Karen Kirby, was arrested and charged with murder. The district attorney’s office was hush-hush on Milligan and Kirby’s exact involvement. All that was known about Kirby was that she was a friend to victim Renee and her sister Rayleen. She was also an acquaintance of Bicknell and Milligan, but didn’t know them that well.

In February of 1978, investigators revealed they had a surprise witness who was in the duplex on the night of the murders. Not only were Milligan, and her friend, Karen Kirby, there during the slaughter, but so was victim Renee’s sister, Rayleen Ferguson.

The mind is a funny thing and Rayleen’s mind had blocked out the trauma it witnessed that night. It was too much to process in minutes or hours or days. Instead, it was like a dream in which all the elements of her memory of that night were elusive, their presence sensed just around the next corner in her mind. Over time, her memory solidified the horrific moments of that night she saw, and by November, Rayleen met with investigators and the district attorney to tell them what she remembered.

That’s when Karen Kirby was arrested.

During a court hearing in February 1978, Rayleen testified she was standing outside the kitchen when the attack started after Renee and Bicknell began arguing.

“I heard screaming,” she said, adding that she saw knives swinging and blood and was then struck on the back on the head and knocked unconscious. (She also may have passed out and hit her head.)

She said she woke up the next morning in Karen Kirby’s bedroom and told the fifteen-year-old girl she had had a bad dream.

“She said, ‘I don’t want to hear about it,’” Ferguson told the judge.

Ferguson also testified she once tried to tell Bicknell about the dream and he agreed and said, “Yes, it does seem like a dream.”

WITH RAYLEEN TESTIFYING AGAINST BICKNELL, and his confession on tape, it was a trial that should have ended in days, not three weeks. Harold, who had pleaded not guilty, said he could not recall killing anybody, and disavowed his taped confession.

Testifying on his own behalf, he said he went over there late that night to confront his cousin Renee. She was going to spill the beans to his long-time girlfriend (the girl who called the detective) about his groping and grunting with his underage girlfriend.

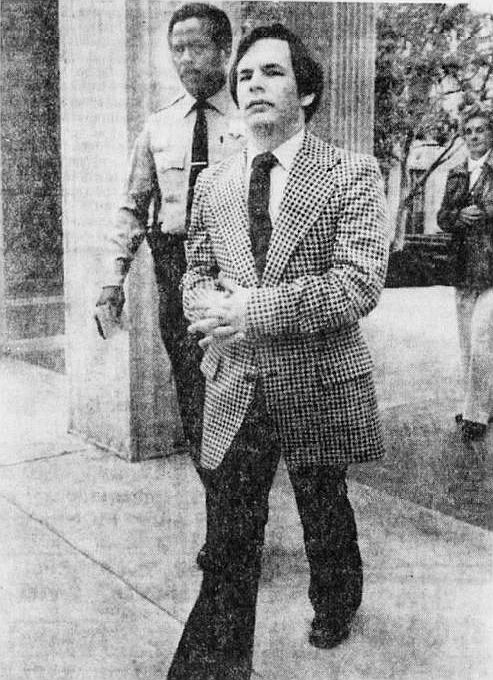

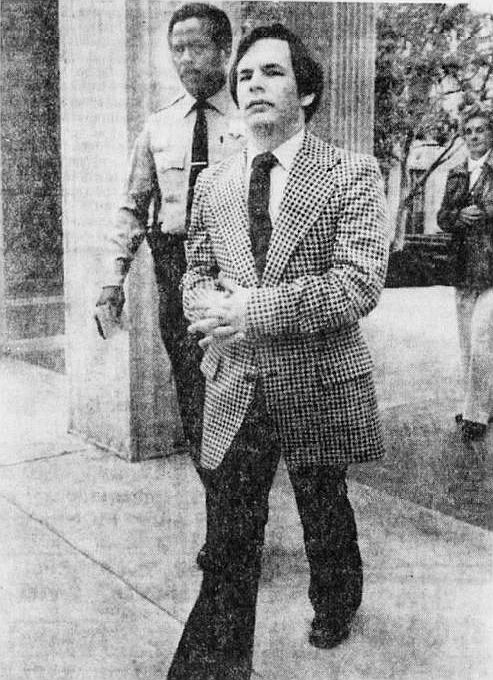

Bicknell is escorted back to the courtroom to hear the verdict.

From the witness stand, Bicknell, talking in the third-person because he had several personalities, stated that he killed for the noblest reason of all.

“When I look back, I see that he was fighting to protect love,” one of his personalities declared in court. Apparently, it was one of the good personalities because that one didn’t like the other one –the stab four members of his family over one-hundred times– personality.

“When I see how much damage I wrought, I abhor that man,” the high school dropout said with some dramatic flair.

Then, although he couldn’t recall killing anyone when he first began to testify, one of his personalities later confessed to jurors that he killed the three younger females. He thoroughly denied killing Grandma, and blamed Karen Kirby and Terrie Milligan. He would never have killed Grandma, it had to have been the other girls, he said repeatedly.

The jury also abhorred the short young man who had wrought so many lives. He was found guilty on April 21. One month later, he was ordered to serve four life sentences—to run concurrently: which really meant one life sentence; which didn’t really mean his entire life because life without parole wasn’t an option until the 1980s; and because it was the 1970s, when prison sentences were ridiculously lenient, his four consecutive life sentences meant that he would be eligible for parole in seven years.

Fortunately, the California Board of Parole Hearings didn’t believe in lenient sentences for lovesick mass-murderers. Harold Arnold Bicknell is still serving his life sentence at Salinas Valley State Prison in Soledad. He is fifty-eight-years-old.

In June 1975, Terri Milligan was convicted in juvenile court of three counts of first-degree murder, and one count of second degree murder. Karen Kirby was convicted of being an accessory, but found not guilty of murder. Just like their involvement in the murders that night, their sentences were not made public.

—###—

UPDATES – 2020, and 2021. Bicknell’s Parole Ultimately Blocked Because of his Denial he was the Perpetrator.

August 5, 2020: After serving forty-three years in California prisons, Harold Arnold Bicknell, inmate B94325, was “granted parole” by the California Parole Board during a July 30, 2020, weekly board meeting. After hearing the emotion-heavy objections to his release by the victims’ family, which is also his family, and reading letters from more family members opposed to the release, the two board panel of commissioners granted the sixty-two year-old a “suitable for parole” recommendation based on his clean record in state prison, his youth at the time, and an abusive childhood as part of the reasons for his release.

Guidelines to the parole board’s process benefited Bicknell under their Youth, and Elderly, considerations. The youth guideline includes “most inmates who were under the age of twenty-six when they committed the offense, and the Elderly program which applies to inmates who are at least sixty-years-old and have served at least twenty-five years behind bars.

It’s important to note that in California, “granted suitable parole,” doesn’t necessarily mean, “granted parole.” The July 30 “granted suitable for parole” is actually Bicknell’s second; the first came more than a year earlier in February, 2019. In June of that year, Governor Newsom over-turned the board’s decision after several family members wrote or called to protest his release.

August 21, 2021: According to a CBS-affiliated station in San Francisco, Harold Bicknell will not be leaving prison anytime soon “…after a state prison board rescinded its decision to issue him parole in the wake of public outrage and emotional pleas from the victims family members.”

In July 2020, the state parole board “granted” Bicknell “suitable for parole” but this decision was appealed to Governor Newsom by the district attorney for Monterrey County (where the murders occurred).

Newsom ordered a new parole board hearing that was held in July of 2021 and during that meeting, the state parole board rescinded it’s earlier decision. In a statement released by the district attorney’s office, the board determined “…that Mr. Bicknell is currently an unreasonable risk of danger to the public because he denied he was the perpetrator, which was implausible, and he failed to address factors leading up to or contributing to the crime.”

Article Link

—–###—–