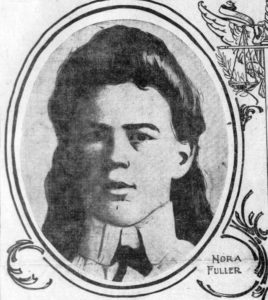

The Mysterious Murder of 15 year-old Nora Fuller, 1902

Home | Feature Stories | The Mysterious Murder of 15 year-old Nora Fuller, 1902Introduction:

On January 11, 1902, fifteen-year-old Nora Fuller disappeared after she left her home. She told her single mother of three that she was going to meet with a man about a job as a nanny after she found his advertisement in the local newspaper. She didn’t come home that night or the next, and the search for Nora Fuller began. Her nude body was found one month later in an empty apartment.

The careful planning and attention to detail by her cunning killer is what makes this case so intriguing. Added to the mystery is that Nora may have been secretly meeting with a much older man, confiding to one friend that he was her boyfriend.

In a story that was on going, with front-page coverage in San Francisco newspapers between January and March 1902, the city was captivated by the mysterious murder of Nora Fuller. This extreme level of publicity put enormous pressure on the San Francisco Police Department to solve the case.

Beneath this introduction is a 3,000-word feature story written by retired San Francisco Police Captain Thomas A. Duke in his book, Celebrated Criminal Cases of America, published in 1910.

According to Duke’s story, the police were eventually able to identify a strong suspect, or so they believed at the time. Unfortunately, he left town before he could be arrested and was never seen or heard from again. What is most fascinating about Duke’s story is the long-running account of circumstantial evidence that police believed connected the murder to this man.

The pressure to solve the case also meant that dozens of other men who were rounded up and interrogated had their names published in the local newspapers as well. With the public’s fear and anger already inflamed by those same dailies, the lives of these men were effectively ruined.

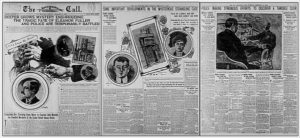

At the end of the story is a link to download a three-page .pdf file containing the front and two interior pages San Francisco Call published on February 11, 1902—three days after Nora’s nude body was discovered. Nearly every square inch of those three pages is devoted to the Fuller murder.

The information within those three pages may not match up with Duke’s account, who wrote it years later and had a more complete view of the crime.

The information within those three pages may not match up with Duke’s account, who wrote it years later and had a more complete view of the crime.

I have also added a link to an October 17, 2016, sfgate.com article.

I will add more links to this feature story, including links to more pdf files, in the near future.

The Nora Fuller Case

Eleanor Parline, better known as Nora Fuller, was born in China in 1886.

Eleanor Parline, better known as Nora Fuller, was born in China in 1886.

In 1890 her father was an engineer on the Steamer Tai Wo. One night he was sitting asleep in a steamer chair on the deck of the vessel while at sea. Shortly after he was seen in this position his services were required in the engine room, but when a helper was sent after him the chair was vacant, and Parline was never seen again. A year later Mrs. Parline married a man named W. W. Fuller, in San Francisco, but seven years later she obtained a divorce.

As she had four small children, Mrs. Fuller experienced much trouble in getting along. In 1902 she lived at 1747 Fulton Street. At that time Nora, who was then fifteen years of age, decided to quit school and seek employment.

On January 6 she wrote to a theatrical agency, and after stating that she had a fairly good soprano voice, asked for employment. Two days later the following advertisement appeared in the Chronicle and Examiner:

“Wanted—Young white girl to take care of baby; good home and good wages.”

At the foot of the advertisement was a note directing anyone answering to address the communication in care of the paper the advertisement was found in. Nora Fuller answered it, and on Saturday, January 11, she received the following postal:

“Miss Fuller: In answer to yours in response to my advertisement, kindly call at the Popular Restaurant, 55 Geary Street, and inquire for Mr. John Bennett, at 1 o’clock. If you can’t come at 1, come at 6. ‘ JOHN BENNETT.”

Mrs. Fuller sent Nora to the rendezvous, and the girl took the postal card with her. About one hour later Mrs. Fuller’s telephone bell rang, and her twelve-year-old son answered.

A nervous, irritable voice, which sounded some like Nora’s, told him that the speaker was at the home of Mr. Bennett, at 1500 Geary Street, and her employer wanted her to go to work at once. (It was subsequently learned that 1500 Geary Street was a vacant lot).

The boy called out the message to his mother, who instructed him to tell Nora to come home and go to work Monday. The boy repeated the message, and the person at the other end said: “All right;” but before any more could be said by the boy the receiver at the other end was hung up. Nora Fuller never came home. A few days later the distracted mother notified the police.

F. W. Krone, proprietor of the Popular Restaurant, was questioned and he stated that about 5:30 on the evening of January 11, a man who had been a patron of his place at different times during the past fifteen years, but whose name he had not up to that time heard, came to the counter and stated that he expected a young girl to inquire for John Bennett, and if she did to send her to the table where he was seated.

The girl did not appear, and Bennett, after waiting one-half hour, became restless and walked up and down the sidewalk in front of the restaurant for several moments. He then disappeared.

This man was described as being about forty years of age, five feet nine inches high, weighing about 170 pounds, wearing a brown mustache, well dressed and refined appearing.

A waiter employed at the Popular Restaurant, who frequently waited on “Bennett,” stated that the much-wanted man was a great lover of porterhouse steaks, but the fact that he only ate the tenderloin part of the steak earned for him the sobriquet of “Tenderloin.”

On January 16 lengthy articles were published in the papers in regard to the mysterious disappearance of the girl.

On January 8, [three days before Nora’s disappearance] a man giving the name of C. B. Hawkins called at Umbsen & Co.’s real estate office, and, addressing a clerk named C. S. Lahenier, inquired for particulars regarding a two-story frame building for rent at 2211 Sutter Street. The terms were satisfactory to Hawkins, but Lahenier asked the prospective tenant for references. He replied that he could give none, as he was a stranger in the city, but as he had a prepossessing appearance the clerk let him have the key after paying one month’s rent in advance. The man then signed the name “C. B. Hawkins” to a contract.

He stated that he was then stopping at the Golden West Hotel with his wife. The description of Hawkins was identically the same as the description of Bennett.

On the following day the real estate firm sent E. F. Bertrand, a locksmith and “handy man” in their employ, to the Sutter-Street house to clean it up.

Many days after this a collector for the firm named Fred Crawford reported that the house was still vacant—judging from outside appearances. He went to the Golden West Hotel to inquire for Hawkins, but he was not known there.

On February 8 the month’s rent was up, and a collector and inspector named H. E. Dean was sent to the house.

Using a pass key he entered, but finding no furniture on the lower floor, he went upstairs, where he found the door to a back room closed. This he opened, but as the shade was down the room was in semi-darkness. He discerned a bright-colored garment on the floor, but as he seemed to know by intuition that something was wrong, he hurriedly left the building, and meeting Officer Gill requested him to accompany him back to the house. The officer entered the room, and upon raising the shade found the dead body of a young girl lying as if asleep in a bed. On the bed were two new sheets, which had never been laundered, a blanket and quilt. An old chair was the only other furniture in the house. Neither food nor dishes could be found. Nor was there any means of heating or lighting the house, as the gas was not connected.

The girl’s clothing was in the bedroom, also her purse, which contained no money, but a card with the following inscription thereon:

“Mr. M. A. Severbrinik, of Port Arthur.”

(It was subsequently learned that this man sailed for China on the Peking three hours before Nora Fuller left home on January 11.)

On the floor was the butt of a cigar, and on the mantle-piece in the front room was an almost empty whiskey bottle. There were no toilet articles in the house except one towel.

Many letters were found addressed to Mrs. C. B. Hawkins, 2211 Sutter Street. They were from furniture houses and contained either advertisements or solicitations for trade. A circular letter addressed to Mrs. Hawkins and bearing a postmark of January 21, 11 p. m., or ten days after the dis-appearance of Nora Fuller, had been opened by someone and then placed in the girl’s jacket, which was found in the room. Mrs. Fuller identified the clothing as belonging to her daughter, and subsequently identified the body as the remains of Nora. No trace was ever found of the postal card Nora received from Bennett.

Dr. Charles Morgan, the city toxicologist, examined the stomach and found no traces of drugs or poisons. Save for an apple, which the deceased had evidently eaten about one or two hours before death, the stomach was empty.

There was a slight congestion of the stomach, possibly due to partaking of some alcoholic drink when the stomach was not accustomed to it. Mrs. Fuller stated that Nora ate an apple shortly before she left home on January 11.

Dr. Bacigalupi, the autopsy surgeon, found two black marks on the throat, one on each side of the larynx, and as there was a slight congestion of the lungs, he concluded that death was due to strangulation. But the child had been other-wise assaulted and her body frightfully mutilated, evidently by a degenerate. Captain of Detectives John Seymour took charge of the case.

B.T. Schell, a salesman at J. C. Cavanaugh’s furniture store, located at 848 Mission Street, stated that at 5 p. m., January 9, a man of the same description as “Hawkins” or “Bennett,” and wearing a high silk hat, called and said that he wanted to furnish a room temporarily. He purchased two second-hand pillows, a pair of blankets, a comforter and top mattress. He insisted that the goods be delivered at night or not at all. This Schell promised to do. The customer then wanted to know what assurance he had that the salesman would not substitute another mattress, and Schell suggested that he put his initials on the mattress as a means of identification. Acting on this suggestion Hawkins used a large heavy pencil and wrote the letters “C. B. H.” on the mattress. After leaving word to deliver the articles that night to 2211 Sutter Street the man departed.

Lawrence C. Gillen, the delivery boy for this firm, stated that he had to work overtime in order to take the articles to the Sutter Street house that night.

When he arrived the house was in darkness. He rang the bell and a man came to the door, and from what he could see with the lights from the street lamps he was of the same description as the man who made the purchases, and he wore a silk hat. Gillen asked him to light up so he could see, but he said, “Never mind, leave the things in the hail.”

Richard Fitzgerald, a salesman employed at the Standard Furniture Company, 745 Mission Street, stated that a man of “Bennett’s” description bought a bed and an old chair from him on January 10, and that he engaged an expressman, Tom Tobin, to deliver the same to 2211 Sutter Street.

Tobin stated that this man was present when he arrived, and requested him to set up the bed in the room where it was found. This man he described as being of Bennett’s ‘appearance.

It is probable that the sheets, towel and pillow cases were purchased at Mrs. Mahoney’s dry goods store, 92 Third Street, which was just around the corner from the Standard Furniture Company. These articles were carried away by the purchaser.

On the floor of the room where the girl’s body was found was a small piece of the Denver Post of January 9, upon which was a mailing label addressed to the office of the Railroad Employees’ Journal, 210 Parrott building.

When this paper arrived at the Parrott building it was given by Exchange Editor Scott to a Mr. Hurlburt, a delegate from Denver to a railroadmen’s convention then in session in the assembly room in the Parrott building. After glancing at it he threw it on a large table, and some other delegate picked it up and took it to Dennett’s restaurant, where he left it on the dining table. The steward of the restaurant, Mr. Helbish, picked it up, and after taking it to the counter began to read it, believing it was the San Francisco Post. He laid it down, and Miss Drysdale, the cashier, glanced over it. She laid it down, and how it got to 2211 Sutter Street remains a mystery.

A seventeen-year-old girl named Madge Graham met Nora Fuller in June, 1901, and they became very friendly. Madge boarded at Nora’s house for a while until her guardian, Attorney Edward Stearns, requested her to move away, because a lawyer named Hugh Grant was a frequent visitor at the Fuller home.

She claimed that Nora Fuller frequently spoke to her of having a friend named Bennett, also she believed that the advertisement was a trick concocted by Nora and “Bennett” to deceive Mrs. Fuller.

She furthermore stated that Nora often telephoned to some man, and that one day Nora requested her to tell Mrs. Fuller that she and Nora were going to the theater that night. Madge did as requested, but she stated that instead of going with her, Nora went with some man. It was also claimed that someone gave Nora complimentary press tickets to the theaters.

A. Menke, who conducted a grocery at Golden Gate and Central Avenues, stated that Nora Fuller frequently used his telephone to call up someone at a hotel, although she had a telephone in her own home a few blocks away.

Theodore Kytka, the handwriting expert, made an examination of the original slips filled out by “Bennett” for his advertisement for a young girl, and also the signature of “C. B. Hawkins” to the contract when he rented the house, and found both were written by the same person.

On February 19 the Coroner’s jury rendered the following verdict:

“That the said Nora Fuller, aged fifteen, nativity China, residence 1747 Fulton Street, came to her death at 2211 Sutter Street in the City and County of San Francisco, through asphyxiation by strangling on a day subsequent to January 11 and before February 4, 1902, at the hands of parties unknown. Furthermore we believe that she died within twenty-four hours after 12 m., January 11. In view of the heinousness of the crime, we recommend that the Governor offer a reward of $5,000 for the discovery and apprehension of the criminal.

“ACHILLE ROSS, Foreman.”

Believing that the person who committed this crime might have changed his address and sent a written notification to that effect to the postal authorities, Theodore Kytka examined 32,000 notifications of changes of address. Of this number he found three signatures that bore considerable resemblance to the Bennett-Hawkins style of penmanship, and one of these three was almost identically the same.

This proved to be the signature of a man in Kansas City, Mo., and Captain Seymour went east to make a personal investigation. It was found, however, that the man had nothing to do with the crime.

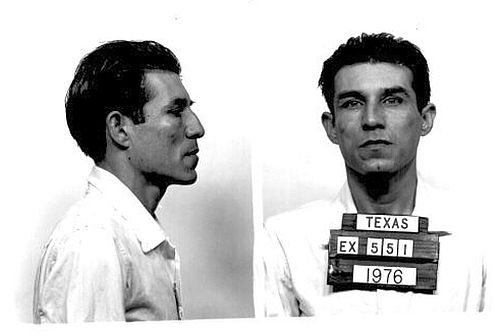

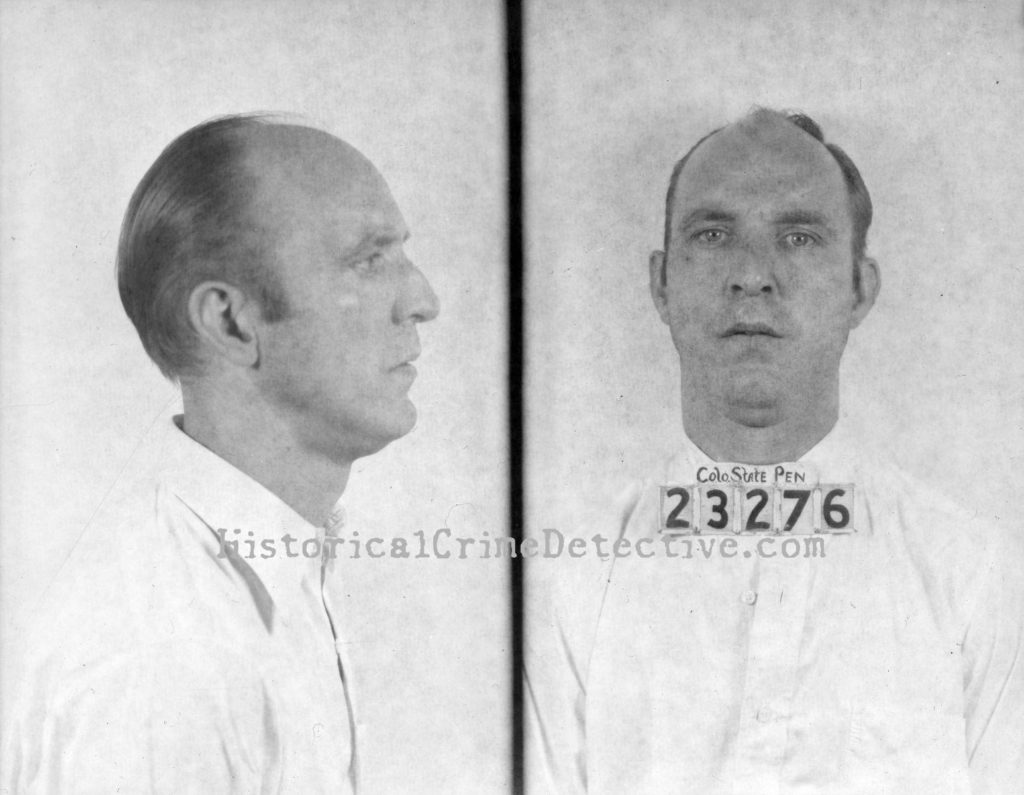

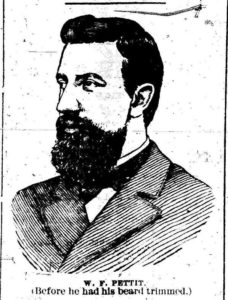

On January 16, five days after the disappearance of Nora Fuller, but three weeks before her fate was known, the papers of San Francisco gave considerable space to the mysterious case. Two days later a gentleman connected with a local paper notified the police department that a clerk in their employ named Charles B. Hadley had disappeared. It was afterward said that he was short in his accounts with his employers.

Detective Charles Cody was detailed to locate the man, and he found that he had lived at 647 Ellis Street with a girl born and raised in San Francisco, who had assumed the name of Ollie Blasier, because of her infatuation for a notorious character known as “Kid” Blasier.

No trace of Hadley was found. Finally the body of Nora Fuller was discovered, and photographs of the signature of “C. B. Hawkins” on the contract with Umbsen & Co., and the “C. B. H.” on the mattress, were published in all the papers.

The Blasier woman had a photograph of Hadley in her room, upon the back of which he had written his name, “C. B. Hadley.” Seeing the great similarity in the handwriting she delivered this to Detective Cody, who in turn delivered it to Theodore Kytka for investigation.

Kytka determined at once that the person who wrote “C. B. Hadley” on the photograph also wrote “C. B. H.” on the mattress, and “C. B. Hawkins” on the contract.

While Hadley had the same general physique as “Hawkins,” it was known that he was always clean shaven. Miss Blaiser stated, however, that she had seen Hadley wear a false brown mustache about the house, and it was subsequently learned that he purchased one at a Japanese store on Larkin Street.

In addition to this, Chief of Police Langley, of Victoria, B. C., made an affidavit to the effect that a Mr. Marsden, a storekeeper in Victoria, B. C., had stated that he had been a companion of Hadley’s, and that while out on a “lark” he had seen Hadley wear a false mustache. Miss Blasier made a further statement substantially as follows:

“I now recall that after the disappearance of Nora Fuller Hadley made a practice of getting up early in the morning and taking the morning paper to the toilet to read.

“On the day of his final disappearance he followed this practice, and after he left the house I found the morning paper in the toilet, and I noticed a long article about the disappearance of Nora Fuller. It was evident that his mind was greatly disturbed on this morning.

“The next day I was making up my laundry, and at the very bottom of the pile of soiled clothing I found some of his garments which had blood on them. I burned them and also his plug hat.

“It is well known that Hadley is partial to porterhouse steaks and that he eats only the tenderloin.

“On the evening of January 16, Hadley telephoned to me that he would not be home. I confess that I suspect he committed this murder.”

Theodore Kytka obtained Hadley’s photograph and altered it by giving him the appearance of wearing a mustache and plug hat. This was shown to different persons who had dealings with “Hawkins,” with the following results:

Tobin, the expressman, said it looked very much like him; Lahenier, the real estate man, said it bore a marked resemblance. Ray Zertanna, who had seen Nora in the park with a man, stated that the picture was a good likeness of this man. Schell, who suggested that “Hawkins” place his initials on the mattress, said it was an exact likeness of Hawkins. Fred Krone, the restaurant man, who had the conversation with “Bennett” on the evening Nora left home, said it was not a likeness of Bennett.

Hadley left his money in a certain bank in this city, where it remains even now.

An investigation was then made as to his past, and it developed that he was an habitue of the tenderloin district, and that he was on the road to degeneracy. His true name was Charlie Start, and his respected mother resided in Chicago.

On May 6, 1889, Superintendent of Police Brackett, of Minneapolis, issued a circular letter offering $100 reward for the arrest of Charles Start for embezzlement.

About two years before the murder of Nora Fuller, Hadley enticed a fifteen-year-old girl into a room and outraged her. He then purchased diamonds and jewelry from a certain large jewelry store in San Francisco and gave them to the girl, who is now a respectable married woman residing in the neighborhood of San Francisco.

The country was flooded with circulars accusing Hadley of this murder and calling for his apprehension, but he was never located.

Many believe that he committed suicide.

Links:

Download 3 page .pdf file of February 11, 1902, San Francisco Call

Read sfgate.com October 17, 2016, article about the case.

—###—

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, November 10th, 2016 under Feature Stories.

Tags: 1900-1919, California, Juvenile, Murder, Mystery, Sex Crimes, unsolved

Comments: none