Vintage Detective Story: Mrs. Evelyn Romadka’s Scandalous Downfall, 1907

Home | Short Feature Story | Vintage Detective Story: Mrs. Evelyn Romadka’s Scandalous Downfall, 1907Story Summary:

The high-society wife of a millionaire trunk manufacturer undergoes an unspecified operation, which alters her personality (or so it is claimed). In 1907 she runs away to Chicago where she falls in love with a black man. To keep him happy, she works as a maid for a string of wealthy Chicago families. While in their employ, she steals expensive items from their homes and brings the goods back to her beau who fences them. She is eventually caught, sent to prison, her husband divorces her, and takes their child. In a later incident, she is proclaimed “Queen of the Vampire Women” of Chicago.

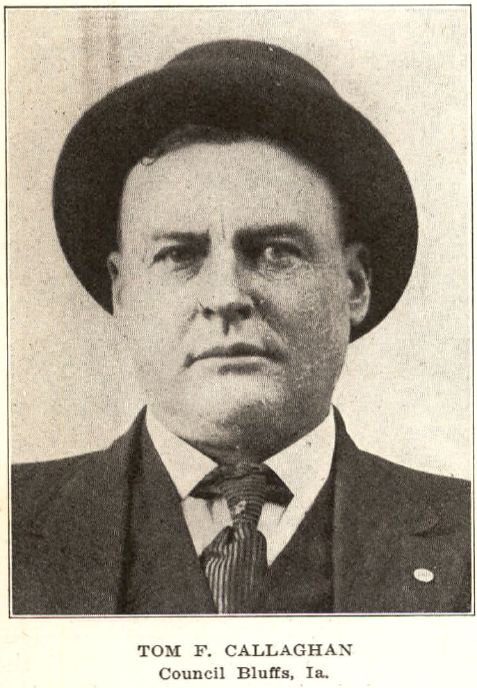

Story written by Lieutenant James V. Larkin, Detective Bureau, Chicago Police Department, and Dalton O’Sullivan, Private Detective, and Author of Enemies of the Underworld, 1917.

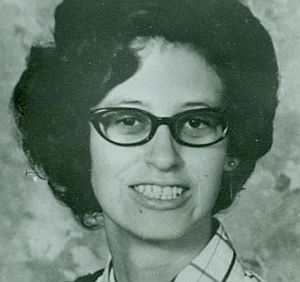

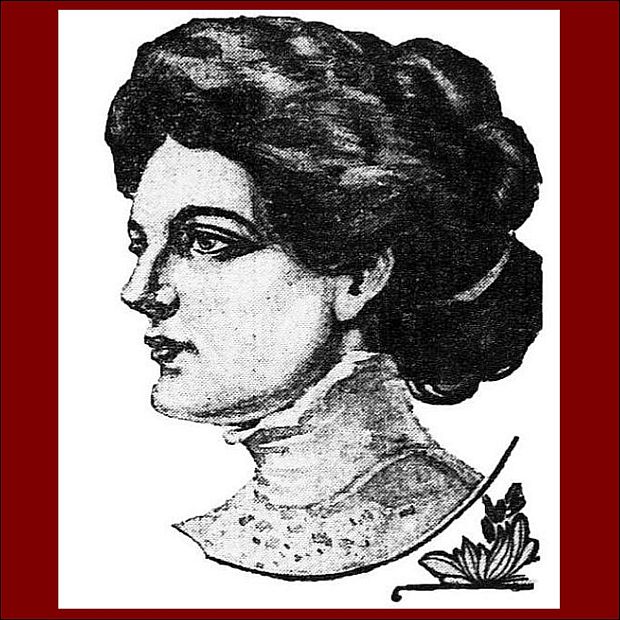

A most remarkable case of dual personality was revealed in the arrest and confession of Mrs. Evelyn Caine Romadka, beautiful wife of Charles Romadka, millionaire trunk manufacturer of Milwaukee, Wis.

Her arrest and conviction was the result of a clever bit of detective work on the part of Lieut. James V. Larkin, of the Chicago detective bureau. Many startling revelations were made at the trial and it developed, that this amazing woman, despite the fact that she possessed an abundance of wealth, had actually burglarized a number of homes in Chicago and had stolen more than $25,000 worth of jewelry.

The Romadka case became notorious in police annals. It revealed the existence of one of those peculiar cases where a person steals, whose only motive, perhaps, for committing theft, is the excitement attendant upon the experience itself; habits developing in a person of abnormal mental faculties.

Prior to her marriage Mrs. Romadka was Miss Evelyn Caine, a pretty school teacher in a small town in the northern woods of Wisconsin. One day Romadka, while on a hunting expedition, happened to meet the little country schoolteacher on her way to school. An innocent little flirtation finally resulted in a love match.

Romadka returned to Milwaukee to inform his parents of his decision to marry the girl. There was much parental objection, principally because of a difference in religious views. Young Romadka finally prevailed upon his family to accept the woman of his choice, and a short time later, he returned home with his bride.

The young couple lived happily for a short time. About a year later a child was born. The young wife fell dangerously ill. An operation was necessary. The best physicians and specialists in the country were summoned. Mrs. Romadka survived but she apparently did not recover fully from the shock of the operation.

One day, she disappeared, and was next heard of in Chicago, where she stopped at the Victoria Hotel. It was learned later that she devoted much time to the meetings of a secret organization.

She studied the ad columns in the newspapers and in this manner obtained positions as a maid in the homes of wealthy Chicago families. She would remain in one place long enough to ascertain where the family jewels were kept and then make away with them.

After continuing these operations for some time, her arrest and conviction followed a robbery at the home of C. E. Beck, 5520 South Park Avenue, Chicago. Mr. and Mrs. Beck were absent from home on Labor Day, and had neglected to lock the front door. It so happened that in leaving the house, the couple was seen by Mrs. Romadka.

She boldly entered the house shortly after the couple disappeared and ransacked every room in the place. In one of the bedrooms, she found a large alligator skin pocketbook, which contained more than a thousand dollars’ worth of jewels.

When Mr. and Mrs. Beck returned home later, they discovered the robbery and immediately notified the police. Lieutenant Larkin was furnished with a complete description of the stolen pocketbook and the jewelry it contained.

A short time after that Lieutenant Larkin stepped into the Baltimore Inn, one of the fashionable cafes in Chicago, and while dining there, he happened to notice a well-dressed woman at a nearby table, in company with a prominent Chicago businessman.

It was not the woman that attracted Lieutenant Larkin’s attention so much as it was the leather pocketbook the woman carried and which she had placed in full view on the table. Its description tallied exactly with the one Mrs. Beck reported had been stolen.

Lieutenant Larkin immediately began an investigation. When the woman left the café, the officer followed. He made some rather sensational discoveries. He learned that the woman, whom he suspected was a Mrs. Romadka, prominent member of society of Milwaukee, and reputed to be quite wealthy.

The police officer learned, somewhat to his consternation at first, that Mrs. Romadka was much given to strange whims and fancies. Among other things, she apparently delighted in posing as a poor maid and seeking employment in the homes of the wealthy, only to remain at a place a few days and then disappear.

All these deductions only strengthened his first impression that in this woman he had discovered one responsible for a number of mysterious robberies in Chicago. She was finally arrested (October 16, 1907) and taken to police headquarters where she was questioned.

Her husband was notified and he hastened to Chicago. No one appeared to be more surprised than the husband to learn that his wife had been working as a maid in the homes of several Chicago people, and his surprise knew no bounds when he was told his wife had been accused of burglary.

At first, the woman declared the leather pocketbook and jewels, found in her possession and identified as having been stolen from the Beck home, were given to her by her husband. Later, she confessed having committed the robbery, together with many other thefts in Chicago.

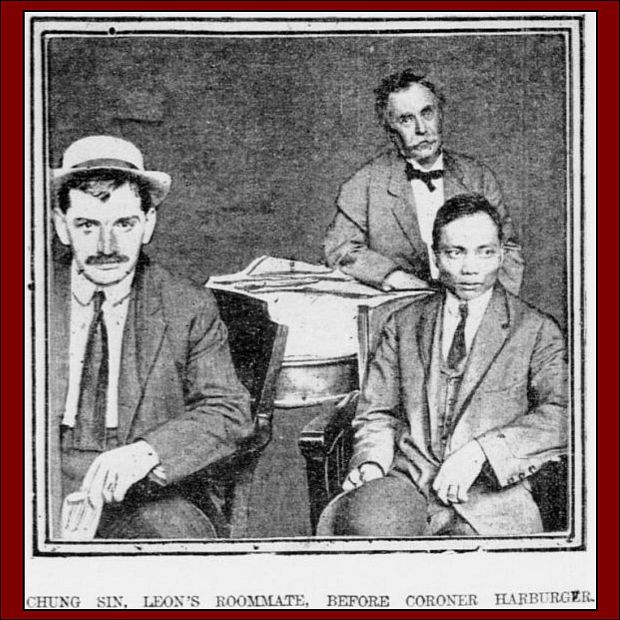

Her confession involved William Jones, a black man in Chicago, with whom the Milwaukee millionaire’s wife had evidently become infatuated. She admitted having stolen jewels and articles of value in order that she could make presents to this lover of hers.

Another piece of clever detective work was necessary to effect the capture of her lover, whom the pretty young wife of the millionaire trunk manufacturer frankly declared she loved and preferred to the man she had lawfully wed.

In making her confession, Mrs. Romadka’s love for William Jones (another source lists his name as Albert Jones) proved even greater than her desire to prevent the shame and humiliation, which her arrest brought upon her husband and his family in Milwaukee.

She told the police she could not recall the name of her African-American lover. At all events, she refused to divulge any information concerning this man that would aid the police in bringing about his arrest.

The police were anxious to capture him, for in his arrest the police hoped to be able to recover some of the jewelry the woman admitted having stolen. Mrs. Romadka was ordered locked up.

Lieutenant Larkin then visited the apartment Mrs. Romadka had occupied and made a thorough search in every room. He found nothing there that appeared to be an aid in determining the name and address of the colored man whom he sought.

The police officer did find, however, tucked in a desk drawer in the living room, a small slip of paper containing several telephone numbers. He traced each of these numbers and finally discovered that one telephone number brought him to the home of her paramour.

When the officer called, he was told by a white woman, who said she was the black man’s wife, and that the man he sought was absent. The wife said she did not know where he had gone or when he would return.

Lieutenant Larkin managed to find quarters near this house and succeeded in rigging up an extension telephone connecting directly with the wire leading to the man’s home. He waited for results and in a short time a call came.

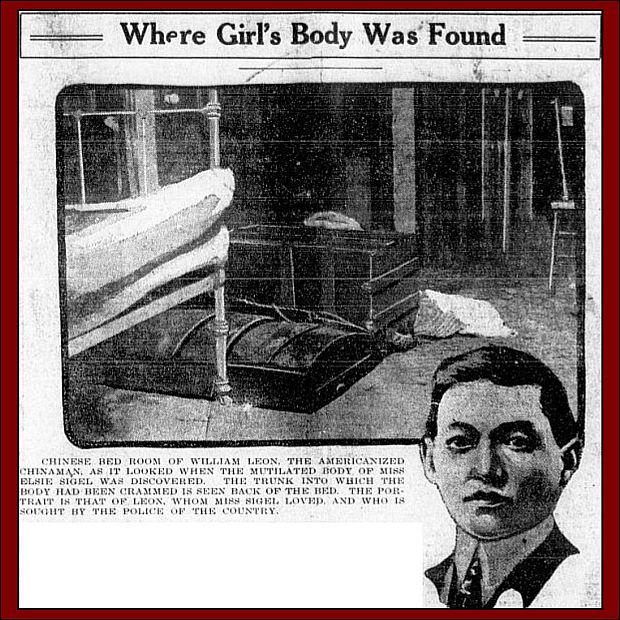

He heard the woman at one end of the wire advise the man at the other end of the wire that detectives had called at the house and that he had better remain away for a time. Lieutenant Larkin also heard the man instruct the woman to destroy a certain trunk in a bedroom in the second floor, and to secrete the contents.

This was enough. The detectives hastened to the man’s home and confiscated the trunk. It was taken immediately to police headquarters and opened. Many of the articles Mrs. Romadka admitted stealing from the homes of wealthy Chicago people were found in the trunk.

Lieutenant Larkin also learned from whence the man had telephoned and located the man at this address. His arrest followed immediately. Later, the man admitted he had taught Mrs. Romadka to rob homes and turn the loot over to him. He converted all the stolen articles into cash whenever possible.

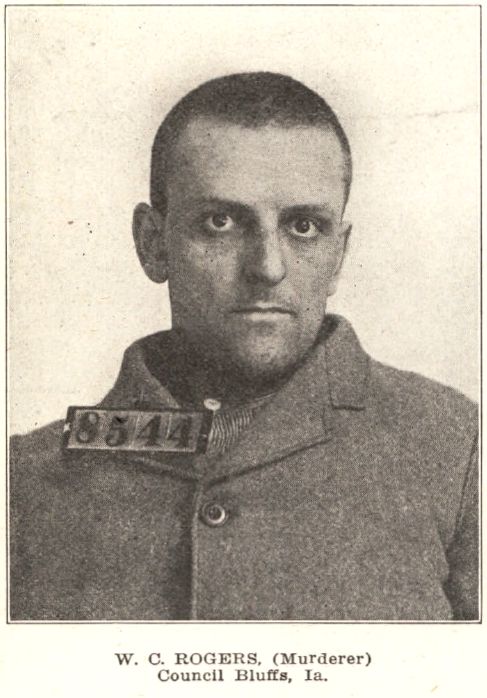

He boasted of having an evil influence over the woman, and told the police she had been but a tool in his hands to do with as he pleased. When confronted with her “negro master,” the woman fainted. Mrs. Romadka was convicted of burglary and the man was found guilty of receiving stolen property.

They were both sentenced to long terms in prison. This ended one of the most sensational cases ever brought to the attention of the police and at the time it attracted nation-wide publicity in the press.

Epilogue: Charles Romadka divorced his wife in 1908 and gained sole custody of their daughter. Because of the scandal caused by his wife, his family shut-off all contact with him and tried to oust him from the company.

Epilogue: Charles Romadka divorced his wife in 1908 and gained sole custody of their daughter. Because of the scandal caused by his wife, his family shut-off all contact with him and tried to oust him from the company.

Evelyn Romadka was released from Joliet Prison on January 5, 1910. In July 1911, police in Chicago were searching for Evelyn in connection with the theft of nearly $1,000 from several bar hopping companions. Two of them, a Kansas City millionaire in town for business and pleasure, along with his date—a local good-time girl, told police that a woman they had partied, “Mrs. Graves,” with slipped “sleeping powder” into their drinks several hours into the festivities.

After they passed out, the woman stole $860 in cash and a diamond stickpin from the Kansas City millionaire, and $80 from his female companion, a woman once known in Denver as the “Pink Pajama girl.”

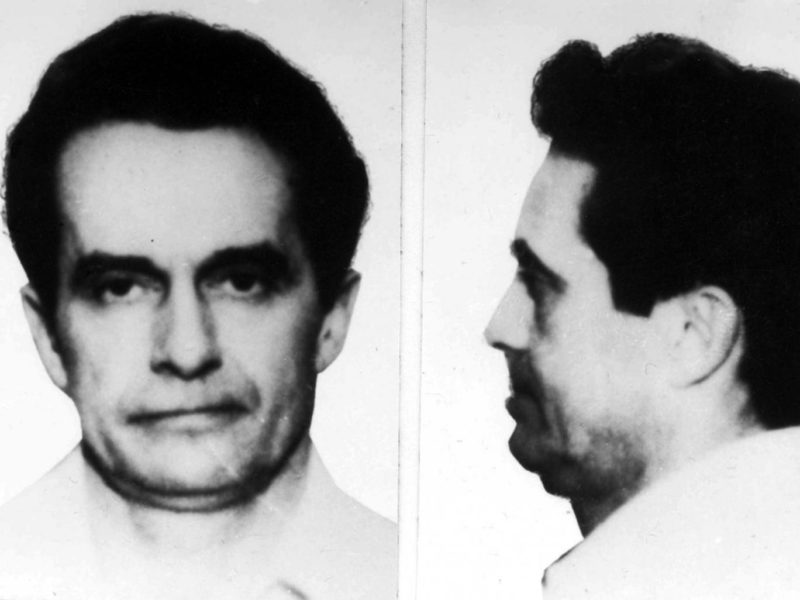

Police learned her true identity after Evelyn’s photograph was identified by the victims from a police mugshot book.

In a sensational new story published the day after the theft was reported, the Chicago Examiner proclaimed Evelyn was actually the leader of a gang of eight “Vampire Women,” who preyed on wealthy male travelers to Chicago. It was her idea, they said, to use sleeping powders to drug the unsuspecting men and steal their money.

The Kansas City millionaire left town before he could swear out a warrant against Evelyn. Although he promised to return to do so, he never did.

Evelyn Romadka apparently left Chicago after this incident. At this time, I could not find any further information about her life or death.

In 1912, The Romadka Brothers Trunk Manufacturing Company of Milwaukee filed for bankruptcy. Her ex-husband had remarried by then, and was working as a turnstile operator at a summer park for $10 a week.

1911 theft story from the Chicago Examiner

1911 theft story from the Chicago Inter-Ocean

—###—

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, September 22nd, 2017 under Short Feature Story.

Tags: 1900-1919, Love Triangle, Petty Crimes, Vintage Detective Stories, Women

Comments: none