Posted from: “Full Pardon Asked For One Who Paid For another Man’s Crime,” The Sunday News and Tribune, Jefferson City, MO, Nov. 2, 1947

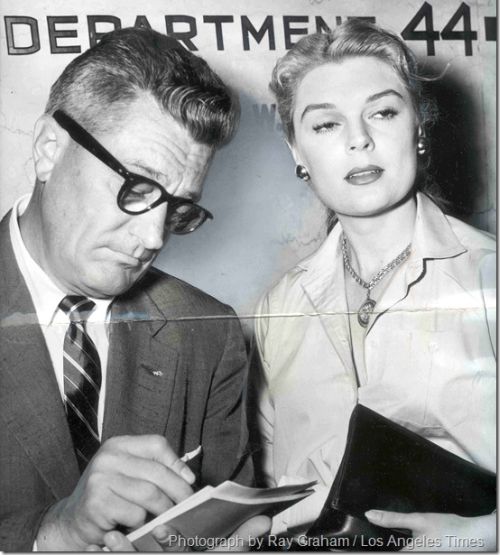

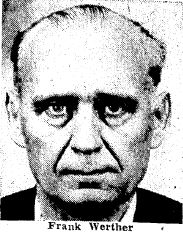

Attorneys for Frank Werther, 47, who served nearly 15 years in the Missouri state penitentiary here and state mental hospitals after conviction of a crime he did not commit, are preparing an application for a full pardon which will shortly be placed before Gov. Phil M. Donnelly for consideration, it has been learned here.

Attorneys for Frank Werther, 47, who served nearly 15 years in the Missouri state penitentiary here and state mental hospitals after conviction of a crime he did not commit, are preparing an application for a full pardon which will shortly be placed before Gov. Phil M. Donnelly for consideration, it has been learned here.

The account of a miscarriage of justice in the Frank Werther case, in which an innocent man was kicked around for 15 long years, reads like something out of a fiction magazine.

On a cold, dark and rainy night early in the fall of 1932, the Frisco railway agent at Neosho, Missouri, sat hunched over his telegraph keys, pounding out train orders and relaying rnesisages for the operation of the many fast trains that thunder incessantly up and down that main line of a great railway.

It was the night trick for this wire operator, named Moore, and it was an especially busy night. His wife, to keep him company, had come to the station with him, and sat over by the glowing stove, listening silently to the clatter of the wires.

Suddenly the door connecting the office with the waiting room was pushed open, and a medium sized man, a complete stranger to Mr. and Mrs. Moore, strode into the room.

Calmly he walked over by the stove, but suddenly he pulled a mean-looking six-shooter, backed the agent and his wife into a corner and announced: “This is a stickup. Give me all the money in that cash drawer, and out of that safe.”

Takes Station Money

There was no help for it, and Moore, taking a good look at the stranger, raked the bills and change out of the drawer under the ticket window, walked over to the safe, reached in. and pulled out the money sack containing a fair amount of currency.

The stranger backed out, keeping them covered, rushed through the door, and was gone in the darkness. Mr. and Mrs. Moore, of course, getting over fright, immediately called the police and the sheriff’s office and, in a matter of minutes, the officers were at the depot.

But their quarry had fled. Careful search of the entire depot, and the railroad yards, produced no thug. No strangers could be found uptown, not in the restaurants, nor the pool halls. Methodically they’ started checking the rooming houses. In one, down on McCord Street, they found a suspicious-looking, suspicious-acting sort of character.

In response to their questions, he stammered and stuttered.

“Yes,” he’d just gotten in Neosho that night. “Yes,” his muddy shoes had Neosho mud on them. “No,” he hadn’t robbed the depot. “No,” he hadn’t stuck up anybody. “Yes,” he had some: money—and he did have; about’ $700—but it was mostly in postal, savings certificates.

Despite his protestations that he had just arrived in Neosho: that night, and was a laborer looking for work, he was lodged in the county jail. The next morning, Mr. and Mrs. Moore came down to the jail, and after studying the suspect for a while declared he was the man. “I’d remember that face anywhere,” said Mrs. Moore. Their identification was positive.

L. D. Rice, then the prosecuting attorney, now a prominent lawyer at Neosho, immediately filed charges against the: suspect, who said his name was Frank Werther, that he was 32 Years old, and that his home was at Winfield, Kans.

He employed three lawyers: Frank Lee, once a congressman from that district; Charles Prettyman, now a retired Neosho attorney; and Phil Graves, still, practicing in Neosho.

In the course of time, with Werther still in jail, his attorneys entered a plea of not guilty for him, and eventually secured a change of venue for his trial. It was set for hearing in Cassville, in that same judicial district, the county seat of Barry County.

Just before his trial his brothers came down from Kansas to see about it. Werther’s funds were exhausted, through lawyer fees, court costs and other expenses. They hired another lawyer. A R. Dunn, now Magistrate Judge in Newton County, to see what he could do. Dunn got into the case too late to do much good. The jury at Cassville found the man guilty of robbing the agent at the Frisco depot in Neosho at pistol point.

Dunn tried to get a new trial, but failed. The prosecuting attorney, elected by the people to see that justice was done by due course of law, felt that the man was guilty. He was supported in his belief by “Cap” Ruark, a special prosecutor who was helping him in that particular case.

Werther was sentenced to serve 10 years in the state penitentiary, following the jury’s conviction. He was received at Jefferson City [Missouri State Prison] on Dec. 5, 1932, prison records show.

Time marched on. Several months later, a special agent for the Kansas City Southern railway, in the line of investigating robberies from freight cars, came up on a hijacker in the railway yards at Harrison, Arkansas. In the gunfight that followed, the robber was critically wounded. Taken to the hospital

He lingered between life and death for several clays, gradually becoming worse. Finally, his condition grew so bad that he, himself, knew that he was going to die. The doctors had known it for some days.

Robber Admits Job

Lying on his iron hospital bed the robber thought back over his trail of crime, which had led him down through Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. Indeed, he had served time for some of his deeds. But, knowing the end was near, he called for the railroad’s special agent who had shot him.

“I want to tell you some things,” he said. “I robbed (so-and-so) over in Kansas. I held up a filling station at Joplin. I held up the Frisco depot in Neosho–”

“When was the Neosho job?” the officer inquired.

“One cold night in the early Fall,” he answered.

“Did you know another man was sentenced to the pen for that job?” the officer asked.

“No, I didn’t,” the dying man said. “But I did that job. Look in my grip over there under the dresser, and you’ll find the money sack that I took from that depot agent that night,” he said.

Sure enough, there was the money sack, with the words Frisco on it in big black type. And the details of the holdup, as he described them, were exactly as Moore and his wife had related them. No doubt about it—he did the job; but another man was serving time for it.

The officers of the county were contacted. They went to Moore and his wife, showed them the picture of the desperado who died in Arkansas, and they said he was the man. They completely repudiated their former identification of the man who was in the pen.

Then Attorney Dunn directed his attention to Jefferson City. He went up to the penitentiary, and uncovered a strange trail of events.

Werther, confined since December of ’32 for a crime he had not committed, had developed signs of increasing melancholy, and depression and finally his condition mentally had become so grave that he was transferred to the state hospital for the insane at Nevada, Mo. This occurred on May 8, 1933.

He remained at Nevada until June 25. 1934, for a year and a month, but became steadily worse, and was transferred to the asylum at Fulton. There he remained.

Attorney Dunn contacted his brothers in Kansas. They came out and canvassed the situation. The Governor and the parole board agreed to pardon the man. But his mental condition was still bad. Perhaps he was better off at Fulton than anywhere else—until, at least, his mind cleared up. So there he stayed.

Gradually, the beneficial results of the training, and care and understanding he received at Fulton, led to a slow return of the man’s normal sense. He was getting better.

On September 24, 1946, he was adjudged cured of any mental illness, and was remanded back to the penitentiary at Jefferson City.

Efforts were then set up in his behalf, but it was not until July 22 of this year (1947), almost 15 years from the time he entered the prison under a miscarriage of jus tice, that he was activated to parole.

Prison officials describe Frank Werther as a mild-mannered, inoffensive, laborer-type sort of person. He was, and is a protestant, and had a ninth-grade education.

Today, Frank Werther, it is reported has a good job, and is making good on it, at Wichita, Kan. His brothers still live down around Winfield.

Judge Dunn still interested in his behalf, advises that he is making plans to ask Governor Donnelly to issue Frank Werther a pardon, a full and complete restoration of citizenship for a man who was guilty only of being in a strange town, on a dark and lonely night, with muddy shoes encountered in tramping around looking for work, and with about $700 in his pockets.

“There was always a doubt in my mind about that case,” remarked Attorney Rice, recently, asked about the incident. “But the officers seemed to have the evidence, and it looked like he might have been the man who robbed the depot, although we never did find a gun on him, or in his room.”

Mr. Rice later joined in signing the application for pardon, as soon as he had learned of the confession made by the thug in Arkansas. And other lawyers in Neosho, including the district judge, also helped in the appeal for clemency.

Frank Werther, through a combination of circumstances had served about 15 years for a crime he did not commit, and had suffered more than ordinary tortures.

—###—

.