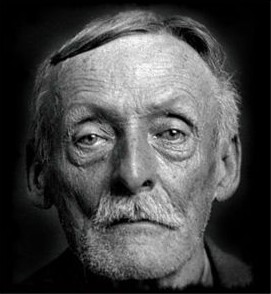

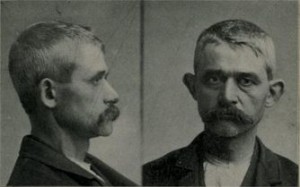

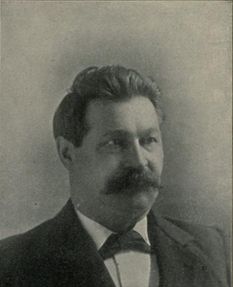

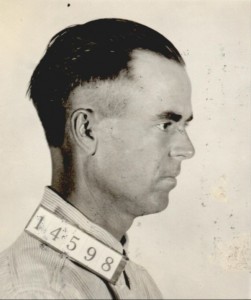

Chicago sausage maker Adolph Luetgert In the latter part of April, 1897, Adolph Luetgert, a powerfully built, coarse appearing man, who conducted a sausage factory at the corner of Hermitage Avenue and Diversey Boulevard, in Chicago, failed in business. He had been married twice. By his first wife he had a grown son named Arnold, and by his second wife, Louise, he had two boys named Elmer and Louis. The family lived on Hermitage Avenue, next door to the factory, and a young woman named Mary Seimmering was employed as a servant in their house.

On May 1, Mrs. Luetgert suddenly disappeared, but her husband was apparently unconcerned regarding her absence and advanced the theory that she had committed suicide because of his failure in business.

On May 4, Deidrich Bicknesse, Mrs. Luetgert’s brother, called to see her, and Luetgert informed him that she had been missing for three days, but admitted that he had not notified the police of the singular incident nor had he taken any steps to locate her.

Bicknesse, observing Luetgert’s utter indifference, had the police notified and Captain Herman Schuettler instituted an investigation.

The press gave much publicity to the mysterious disappearance and the police began a general search, even going to the extent of dragging the river for a considerable distance, but nothing was discovered.

Finally Captain Schuettler decided to confine his investigation to the factory in general but to a large vat therein in particular, and a rapid solution of the mystery followed.

In the sediment in the bottom of the vat, two gold rings, one having the initials “L. L.” engraved inside, a tooth, and two corset steels were found.

The rings were positively identified as the property of Mrs. Louise Luetgert, and in the yard where the bones from the animals were thrown, a part of a skull and other pieces of human bones were found.

It was learned that during the period between May 2 and May 17 Luetgert made many efforts to gain an entrance to the factory, but was always refused admission by the sheriff’s deputies who were in charge.

On May 18, Luetgert was arrested and four days later was indicted by the grand jury.

He attempted to gain his freedom on a writ of habeas corpus but failed.

On August 7, the prosecution obtained a corpse, and placing it in the identical vat where Mrs. Luetgert’s body was destroyed, boiled it in caustic potash for two hours. At the expiration of that time, nothing remained of the fleshy parts of the body but a fluid and all of the bones, except the larger ones, were completely destroyed.

This proved that their theory was correct.

On August 24, Luetgert’s trial began before Judge Tuthill. The attorney for Luetgert claimed that he had also made a test with a corpse, but that the boiling process did not dissolve it. The contention of the defense was that no crime had been committed and that Mrs. Luetgert was not dead, but was remaining in seclusion. A letter was received by Alderman Schlake signed by “Loisa Luetgert,” in which the missing woman was represented as saying that she was then living with friends in Chicago, but it was shown that the handwriting in no manner resembled that of the missing woman and the missive was evidently sent for the purpose of con¬fusing the authorities.

Nicholas Faber and Emma and Gottliebe Schimpke testified that they saw Luetgert enter his factory about 10 p. m. on the night of May 1 with a woman about the size of Mrs. Luetgert.

Frank Bialk, a watchman in the factory, which had been shut down since the failure, testified that on this night, Luetgert instructed him to bring down two barrels of caustic potash and place them in the boiler room, and that Luetgert then poured the contents of both barrels in one of the vats. The watchman was instructed to keep up steam all night and at 10 p. m. he was sent by Luetgert to the drug store after some nerve medicine.

When he returned, Luetgert was in the room where the vats were located and had the door locked.

Bialk furthermore testified that he resided at the home of Police Officer Klinger and that on May 6 Luetgert called on him. After concealing the officer under the bed in Bialk’s room, Luetgert was admitted to the room and in suppressed excitement asked if the officers had discovered anything at the factory. Bialk answered “No,” and Luetgert, with a show of relief, remarked: “That’s good.”

He then admonished the watchman to tell the police nothing and promised that when the factory re-opened, good positions would be provided for Bialk and his son.

Frank Odorfsky, an employee of the factory, who assisted Luetgert to put the caustic potash in the vat; testified that in all his experience in the factory he had never seen caustic potash used there before.

Mrs. Agatha Tosch, whose husband conducted a saloon opposite the factory, testified that she saw smoke coming from the factory chimney on the night of May 1, although the factory was supposed to have been shut down at the time.

She also stated that Luetgert visited her on the following day and requested her to say nothing about the smoke as it would get him in trouble.

Chas. Hengst stated that he was passing the factory about 10 p. m. on May 1, and heard a noise similar to that made by a person screaming.

Chemist Carl Voelker testified that there was no occasion for caustic potash in a sausage factory.

Mrs. Christina Feldt, a widow with whom the defendant had at one time been infatuated, testified that Luetgert often expressed his hatred for his wife and intimated that he would get rid of her.

Dr. Chas. Gibson and Professor De la Fontaine testified that the masses of soft substance which had presumably boiled over the vat was flesh that had undergone burning by potash.

Particles removed from the drain pipes leading from the vat were then produced and proven to be portions of human bones.

Luetgert handled these exhibits in the most cold-blooded manner, and demonstrated that he was devoid of all feeling.

Professor George Dorsey of the Field Columbian Museum, testified that one of the bones found in the pile of animal bones was the upper portion of the left thigh bone of a woman.

During the trial, Chas. Winthers of 250 Orleans Street, was arrested for attempting to intimidate Mrs. Tosch, the witness who saw the smoke coming from the chimney in the sausage factory on the night of May 1.

Captain Schuettler testified regarding the indifference exhibited by Luetgert as to the fate of his wife, and as to the result of his official investigations.

The defense began on September 24, and several persons testified that since May 1 they had at different places seen a woman who resembled Mrs. Luetgert.

It was the theory of the prosecution that Luetgert, tiring of his second wife, was anxious to get her out of the way so that he might marry Mary Seimmering, the family servant. On September 25, this girl testified for the defense and described Luetgert’s “kind treatment” toward his wife.

She denied having been on intimate terms with Luetgert, although members of the grand jury were subsequently produced who swore that she had told them of her improper relations with the defendant.

The defense then produced a number of experts for the purpose of offsetting the testimony given by experts for the prosecution.

William Charles, Luetgert’s business partner, testified that the caustic potash was bought for the purpose of making soft soap, as they intended to clean the factory prior to turning it over to an English syndicate.

To rebut this testimony, Deputy Sheriff Frank Moan swore that when he took possession of the place there were over 100 boxes of soap in stock, thus showing that there was sufficient on hand for cleaning purposes.

On October 18, the case was submitted to the jury and after deliberating for sixty-six hours they failed to agree, nine favoring a conviction and three voting in favor of an acquittal.

On November 29, 1897, the second trial began and Luetgert made an appeal to the public for financial assistance, but few people responded.

On January 19, 1898, the defendant took the stand in his own behalf for the first time and the police experienced great difficulty in handling the crowd.

The trial resulted in a conviction and on May 5 Luetgert was sent to the Joliet State prison for life.

At 6 a. m. on the morning of July 27, 1899, Luetgert left his cell and returned shortly afterward with his breakfast in a pail, but just as he was about to eat it, he dropped dead from heart disease.

After his death, Frank Pratt, a member of the Chicago bar, stated that he visited Joliet in February, 1898, to consult a client named Chris Merry, and being somewhat of a palmist he asked Luetgert if he wanted his “hand read.”

The latter consented and Pratt told Luetgert that he possessed a violent temper and at times was not responsible for his actions. Pratt stated that Luetgert then virtually admitted that he killed his wife when he was possessed of the devil. Pratt is quoted as saying that he regarded this admission as a professional secret and therefore did not feel at liberty to divulge it until after the death of Luetgert.

It is said that Luetgert also made similar admissions to a fellow prisoner.

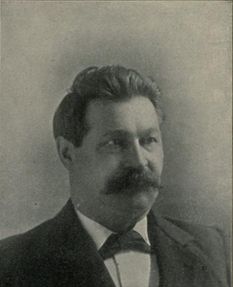

This story comes from the book: “Celebrated Criminal Cases of America,” by Thomas Samuel Duke, The James H. Barry Company, 1910.

—###—