Blame it on the Teacher, 1964

Home | Rediscovered Crime News | Blame it on the Teacher, 1964Summary: Student with poor grades murders one woman, injures two others including his English Tutor.

Story 1: “Tucson Youth Goes Wild, Kills Woman,” by Dominic Crolla, Tucson Daily Citizen, May 16, 1964 pages 1 and 6.

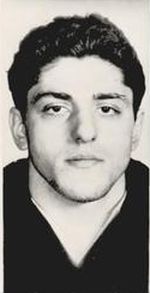

A bitter argument over his poor marks in English triggered a wild rampage early today by an enraged 16-year-old Tucson High School student which ended in the death of a woman and beatings of two other persons.

The youth, Peter B. Damskey, 3663 N. Cactus Blvd. [Tucson, Arizona], was taken into custody by sheriff’s deputies at his home where they found him peacefully asleep about a half hour after the bloody melee.

Lying near his home were the victims—the dead woman, Mrs. Margaret Agnes Eckstrom, about 50, with a butcher knife protruding from the right side of her neck; her unconscious husband, Carl, a painting contractor, and Miss Barrie Ryan, 28, a University of Arizona English instructor.

Damskey, who has been turned over to juvenile authorities, was being tutored privately in English by Miss Ryan. Both she and Carl Eckstrom are in satisfactory condition at Tucson Medical Center. Miss Ryan suffered bruises on the face and Eckstrom is being treated for facial and head cuts.

According to Sheriff Weldon V. Burr, the youth also tried to set fire to Miss Ryan’s house, at 2707 Clay Alley. Burr said the youth’s father, George B. Damskey, owner of Damskey’s Cigar Store, 131 N. Stone Ave., had told him his son had been a patient for two years at the Tucson Child Guidance Clinic.

The Eckstroms’ home is at 3625 Clay Alley. They are neighbors of the Damskeys and Miss Ryan. And they became involved when they saw the Ryan house on fire.

Sheriff’s Deputies Kenneth Chronister and Reggie Russell and Capt. James McDonald were told the Eckstroms found Miss Ryan lying outside the house unconscious.

While Mrs. Eckstrom ran back to her home to call for an ambulance and the sheriff, her husband attempted to put the fire out.

Damskey was interrogated for some two hours after being taken into custody, at which time, according to Burr, he gave this account of what had happened.

He said he had gone over to see his tutor at about 1:30 a.m. to discuss his English marks with her. She ordered him out, but he wouldn’t leave. A struggle developed, during which he shoved her and punched her with his fists.

She ran out of the door screaming, but he tackled her, tried to stifle her screams for help, and then punched her four or five more times on the face. Burr said that Damskey had stated that he then took a “stick,” later changing the description to a “club.” and then beat her unconscious.

After that, the sheriff said, the boy tried to set fire to the house by turning on the gas in the oven, and shoving a silken scarf or paper inside.

The gas ignited from the pilot,” said Deputy Russell. He managed to set fire to the drapes, some piano music and his English lesson papers.

The youth said that when Carl Eckstrom arrived he said: “You’re a Boy Scout, get this fire out.” And they both turned a garden hose on the flames and put the fire out.

Once the fire was under control, Eckstrom grabbed Damskey by the shoulders and shook him several times. The youth, whose father told Burr he had taken karate lessons, broke loose and punched Carl Eckstrom to the ground, knocking him unconscious with a blow across the face with a glass coffee pot.

The youth then went to the Eckstrom home which was locked. Mrs. Eckstrom was inside, trying to call for help as Damskey, using his elbow, smashed a glass panel in the kitchen door and gained entry to the house.

Mrs. Eckstrom grabbed a butcher knife and ran out of the front of the door. Damskey ran after her. Shortly before he caught up with her, she turned and faced him, the knife held high in her right hand, the blade pointing downward.

Damskey told Burr he feinted and she plunged down with the knife, missing him. He said he grabbed her wrist, forced her to the ground, and then twisted her wrist, her hand still holding the knife, back toward her neck.

“I twisted her wrist and drove the knife into her neck once, maybe twice,” he told the sheriff.

Burr said later there were two “good” fingerprints on the knife, but they had not yet been identified.

Damskey told the sheriff he had not handled the knife at all. According to Burr, the youth then went back to his home, got into his pajamas, hung his bloodied clothes in a closet, and then went to bed, apparently putting out of his mind completely the savage attacks.

The youth, described as about 5 feet 5 inches, slender but having heavy hands, told the sheriff’s deputies he went “mad” while arguing with Miss Ryan.

The youth’s report that Miss Ryan was awake when he went to her home conflicted with her statement that she was awakened by Damskey.

Damskey told deputies his son wanted to major in sciences, but poor marks in English apparently were holding him back. That was why he started taking lessons from Miss Ryan.

“In trying to determine his ‘likes and dislikes’ we learned that he was quite a student of the Nazis and the Third Reich. He apparently had studied the Second World War very closely, concentrating on battles the Nazis had won and lost,” Burr said.

It was through this close interest in the Nazis that sheriff’s deputies were able to extract the whole story from him. Burr said he was impressed when Cronister started speaking to him in German and demonstrated knowledge of the German’s and their battles.

Paul Charters, assistant chief probation officer here, said he had no knowledge “of any referral” on the youth before. He added that Damskey will be given psychiatric and psychological tests Monday, “although the boy has had these tests before.”

Three Years Later…

Story 2: Judge Rules Damskey Fit for Sentencing, Tucson Daily Citizen, Dec. 12, 1967, page 12.

Superior Court Judge Robert 0. Roylston ruled today that confessed teen-age slayer Peter B. Damskey is mentally fit to be sentenced for the May 16, 1969, butcher-knife murder of Mrs. Margaret Eckstrom, 50. Roylston set sentencing for 9 a.m. Dec. 22, at which time a bearing will be held concerning the nature and length of sentence.

Damskey, 19, could receive 10 years to life in prison, but his attorneys are expected to ask that he be granted probation on the condition that he go to a private mental institution.

Roylston ruled Damskey legally sane after listening to the testimony of Drs. Robert Cutts and Gabriel Cata. Both recommended that the youth be confined to a mental hospital. Cutts said Damskey is “crafty.” The doctor added: “He presents a good facade, but, in my opinion, Peter is still a sick boy.”

Cata testified that the defendant “intellectually” knows the difference between “right and wrong.” He said that “emotions” could interfere with Damskey s judgment, however.

Cata said that during an interview, Damskey talked about “going to school next year . . . which is quite unrealistic.”

The youth pleaded guilty to Mrs. Eckstrom’s murder and was committed to the Arizona State Hospital in Phoenix. He was recently released as being in “a state of complete remission.”

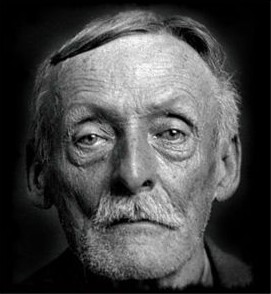

Story 3: Young Slayer Dies of Coronary Illness, Tucson Daily Citizen, Oct. 23, 1974

Peter B. Damskey, who was serving a 25 year-to-life sentence for the 1964 butcher-knife slaying here of a 50-year-old woman neighbor in an incident that began with an argument over poor grades, has died at the Safford Prison Farm.

State Department of Corrections spokesmen said Damskey, who was 16 at the time of the killing, died of coronary insufficiency and coronary arterial sclerosis. He also suffered from Hodgkin’s disease.

Damskey, who was 26, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in the May 16, 1964, stabbing death of the neighbor, Mrs. Margaret Eckstrom.

A Tucson High School student at the time of the slaying, Damskey was arrested by sheriff’s deputies following a bitter argument over his poor grades in English.

The argument left Mrs. Eckstrom dead — felled by a butcher knife wound to the neck — and her husband, Carl, and another neighbor, Miss Barrie Ryan, a University of Arizona English Instructor, severely beaten. Miss Ryan had been tutoring Damskey in -English.

Formal sentencing was delayed while he was confined to the Arizona State Hospital for about three years after the slaying. In 1967, Damskey was declared sane, sentenced and transferred to the Arizona State Prison.

Three years ago, Pima County Superior Court Judge Robert 0. Roylstun ordered that the original 25-year-to-life term be predated to the’ day in 1964 he confessed to the murder of Mrs. Eckstrom.

The re-sentencing voided the 1967 sentencing date, and would have made him eligible for parole earlier. In an interview last year, Damskey said he expected to be paroled in 1979 or 1980.

Before his transfer from the Arizona State Prison at Florence to the Safford facility, Damskey was active in prison sports and worked as a activity coordinator.

—-###—-

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, June 25th, 2014 under Rediscovered Crime News.

Tags: 1960s, Arizona, bizarre, Juvenile, Murder

Comments: none