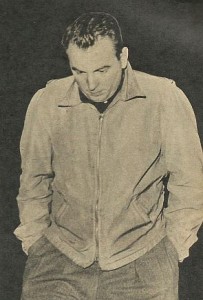

Savage Killer Timothy McCorquodale, 1974

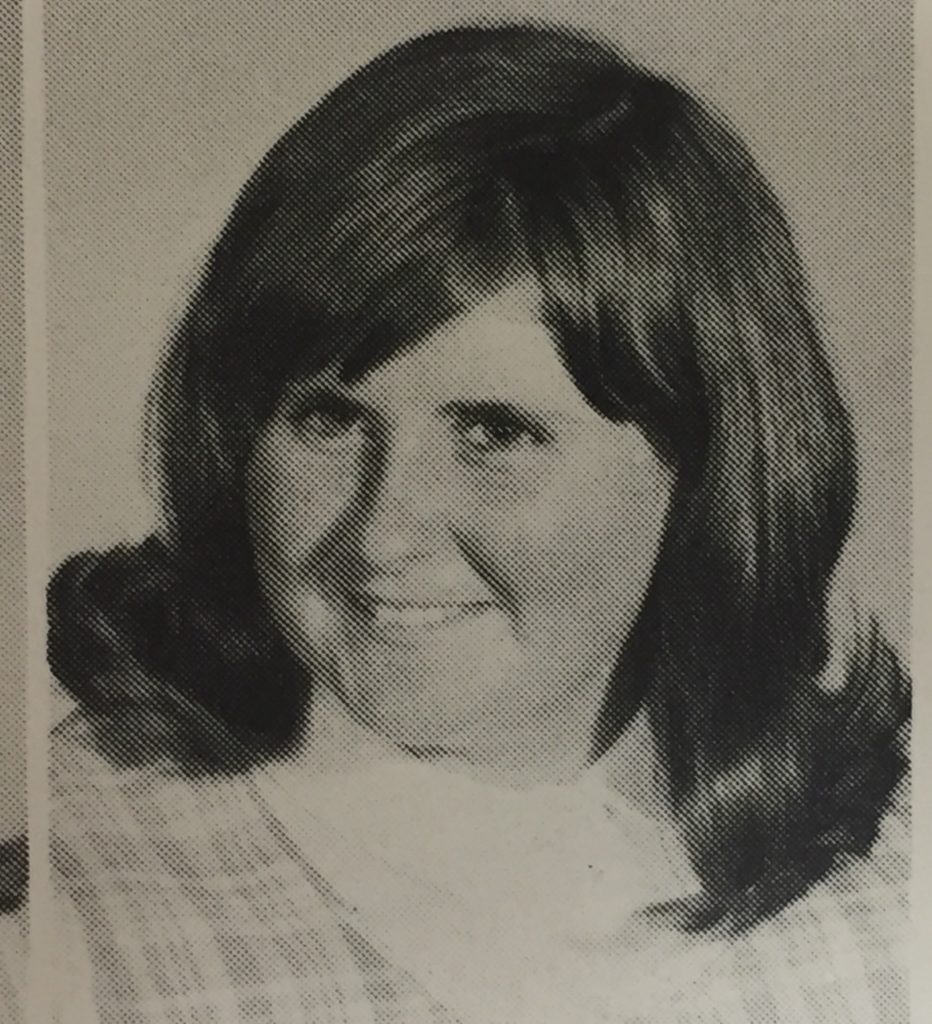

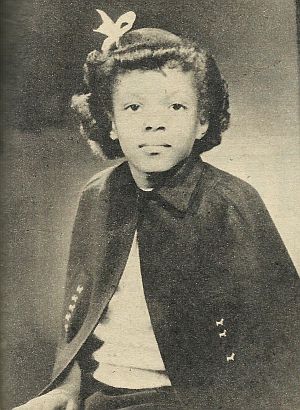

Home | Feature Stories | Savage Killer Timothy McCorquodale, 1974In Memoriam. Donna Marie Dixon, 1956 to 1974

Although it has been more than forty-years now, the memory of Donna Marie Dixon has not been erased by time. Her existence, her time with us in this world, lives on in the memory of four of her friends who wish to honor her, remember her, and pass along their love in the following statement. It is written by her friend Pam, who is mentioned in the story below, as well as Lauren, Susie, and Rick.

“Donna Marie Dixon was a sweet loving girl. Her loves in life were food, you ate what mama fixed, favorite food was food! Her favorite song was “Stairway to Heaven,” flowers were mums, birds were cardinals and her goal in life was to work with animals. Pam, her best friend, moved back to Newport News after the crime. Imagine how traumatic to be asked to identify you friend but don’t even recognize her. There is not a day that goes by that she doesn’t think about Donna Marie Dixon. She wants the world to know that “Leroy” or “Lee” does exist and she saw him get into the cab with Wes, Bonnie and Donna. We are looking for some pictures of Donna to add to the web and hopefully someone out there knows new information about this case. We need justice for Donna, gone way to soon….RIP”

Since the story below was published, it has become the most popular one on this blog. It has even generated interest into learning the identity of Timothy McCorquodale’s accomplice with the newly created thread, “Who was Leroy?” on the subreddit, Unresolved Mysteries, at reddit.com. According to Donna’s friends, an Atlanta detective is looking into the old files in this case in order to learn the true identity of “Leroy.”

Updated: June 30, 2016

Story by Jason Lucky Morrow

January 17, 1974,

Clayton County, Georgia,

outskirts of Atlanta

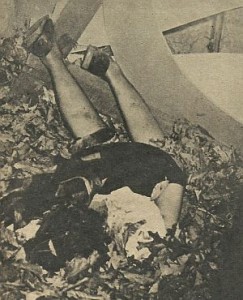

TO THE CLAYTON COUNTY police officer on routine patrol, the white object near the shoulder of Slate Road and Highway 42[1] looked like a bag of trash. Illegal dumping was a fairly common occurrence in his line of work and he stopped to check it out. When the officer walked around to the side of the road and shined his flashlight, the large pale object had legs, arms, breasts and a head.

Sometimes, flashlight beams reveal things we don’t want to see and this time was no exception. Looking down, the lawman was appalled to see that the young, shapely girl looked as if she had been tortured to death. Unsure if whether the nude female was alive or not, the policeman stood closer. If she was alive, he needed to render immediate aid but when he touched her cold skin, he knew.

The officer radioed backed to headquarters for assistance and immediately began securing the scene. It was truly a horrific sight. The girl’s face looked like a distorted mass of barely recognizable features. Her nose was flattened and she was covered in purplish bruises with severe swelling that pushed everything out of position.

It got worse as he shined his flashlight over her body. Long, thin welts on her thighs indicated she had been whipped. Small round scorch marks over her torso and breasts indicated the tell-tale signs of cigarette burns. Hot red candle wax had been poured on her stomach, inner thighs and between her legs. When thrown out of the car, the body fell on its side with its arms and legs protruding out in abnormal directions—an indication they had been smashed and broken either before or after death.

Whoever murdered this poor girl was no master criminal. Before his colleagues even arrived, the officer found a good tire track by the road just waiting for a plaster-of-Paris cast. Next to the girl was a blood-stained portion of a cardboard box with black tape wrapped around it and what looked like fibers, possibly carpet fibers, adhered to the tape.

Despite their mistakes, her killer or killers had done one thing right; removed her clothes and stole her identification. But there was more than one way to identify a corpse and an ambulance carried the girl’s broken body to the Fulton County medical examiner’s office in nearby Atlanta where her fingerprints may indicate who she was. In a worst case scenario, the M.E. could make a dental impression.

Although Atlanta and the suburbs which surround it have grown exponentially since 1974, it was much smaller then. But to those who lived there at the time, the city had grown fast in the few decades leading up to 1974. As part of that rapid growth, hippies, motorcycle gangs, runaways and hustlers were all attracted to a mid-town Atlanta district known as the “The Peachtree Strip.”

The Strip, as it was more commonly called, was a sleazy area of run-down motels, darkened strip-clubs, dangerous bars, and cheap apartment houses. Since there were no local missing person reports of a five-foot four-inch girl with brunette hair weighing close to 140 pounds, Clayton County investigators worked off the assumption that she was one of Atlanta’s many runaways.

“Literally, thousands of runaway teenagers find a home among the dubious denizens of ‘The Strip.’ It was the thinking of detectives that the female victim might have come from among their number,” a crime magazine reported the following year. “It is nearly impossible to walk in the streets for the clusters of the unwashed and non-working, most of them young, and most of them looking for a victim or a handout.”

On Saturday, two days after the gruesome discovery, a confidential informant working for Sheriff Earl Lee of nearby Douglas County provided investigators with two names possibly tied to the woman’s death. One was a young woman in her twenties known as “Bonnie,” while the other was a man known as “Wes” or “West,” also in his twenties. Both subjects were known to frequent ‘The Strip.’ For Sheriff Lee, his informant was as solid as they come and had always provided them with good tips in the past. If he said to look for a “Bonnie” and “West,” that’s what they needed to do.

With a solid lead pointing to the rundown Strip, a special squad of Atlanta homicide investigators was formed to probe possible connections to an area they knew well. They began a slow, building by building, person by person canvas of the Strip and it didn’t take long for them to find people who knew the victim. The Strip may have had its share of petty thieves, drug-dealers, pimps and hustlers, but when it came to murder, detectives knew someone would eventually talk.

And that’s exactly what happened. Talking to a young couple inside a bar one afternoon, a teenage girl told detectives the victim was a friend of hers who had hitchhiked to Atlanta after running away from her parent’s home in Newport News, Virginia. Her name was Donna Marie Dixon and she was just seventeen years-old.

The young girl was asked to identify her friend at the morgue but she was unable to recognize Donna’s battered face. The victim’s parents were then contacted in Newport News and the sad information was passed on to her step-father who broke the news to her mother. When they came to retrieve their daughter’s body later that next week, Donna’s parents made a positive identification. By then, however, police would already know for certain it was young Donna Marie Dixon.

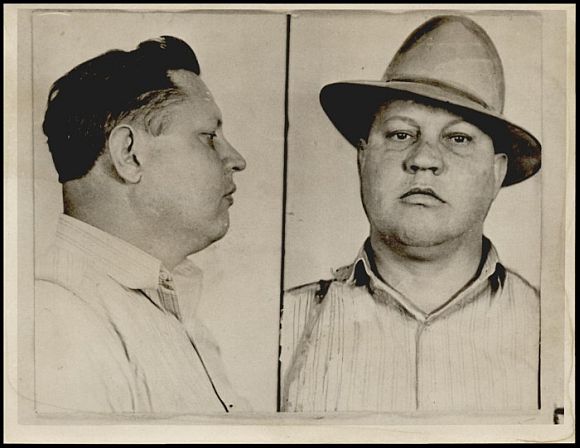

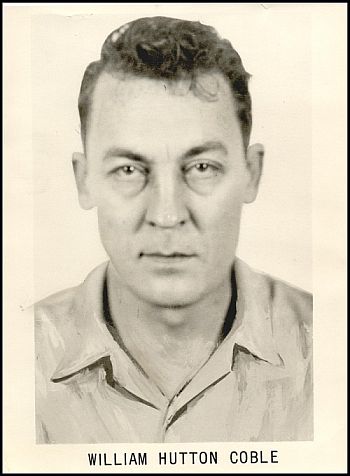

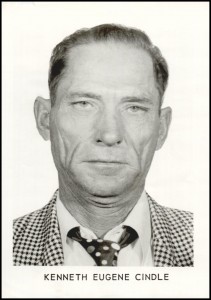

As it turns out, there were a lot of “Bonnies” associated with the Strip, but the small-time criminals, who often knew more than police, could associate the name “Bonnie” with the name “West” who turned out to be Wes McCorquodale, a tall, baby-faced twenty-one-year-old from Alma, Georgia who had a slight-build and a full head of stringy blond hair that covered his ears. During the colder months, McCorquodale would often wear the same coat which was described to detectives. The two subjects lived in an apartment on Moreland Avenue in southeast Atlanta, the same direction from The Strip which led to the spot where the victim was dumped.

As the two Atlanta detectives left the bar where they had learned their suspects’ names, they got in their car and were about to start for the apartment complex when they noticed a slightly-built young man with blonde, stringy-hair wearing the same color coat they were told to look for. After they slowly got out of the car and approached the him, they identified themselves and demanded to know his name.

It was Timothy Wesley McCorquodale.

During his interrogation at headquarters, McCorquodale told detectives “Bonnie” was his girlfriend, Bonnie Succraw Johnson. He gave police her address and place of work where she was picked up and brought in for questioning.

Although McCorquodale quickly waived his right to counsel and gave a full confession, the statement from his girlfriend, Bonnie, was the one used during his trial. The two lived together in an apartment in the 700 block for Moreland Avenue which they shared with her three-year old daughter by another man, and a female roommate named Linda Deering, who was eight months pregnant. Both Linda and Bonnie were given immunity in exchange for their statements which were some of the most sickening, cold-blooded and shockingly horrific documents ever presented in a Georgia courtroom.

During the early morning hours of January 17, Bonnie said she left the bar where she worked and met up with her boyfriend at another nightspot. Inside, McCorquodale was with Donna Marie Dixon where he was accusing her of stealing $50 from his acquaintance, “Leroy.” Despite the runaway’s repeated and steadfast denials, Bonnie’s boyfriend couldn’t seem to let it go and she tried to calm him down. Bonnie then took Donna into the ladies room where she did a full search of the plump girl which turned up nothing. Undeterred, McCorquodale then insisted Donna gave the money to a black man he saw her talking with and assumed was her pimp.

Outside the nightclub, McCorquodale let loose a barrage of racist insults over her assumed association with a black man. Then, McCorquodale, Donna Dixon, “Leroy,” and Bonnie caught a taxi which they took back to Bonnie’s apartment. Inside, McCorquodale’s obsession over the girl’s supposed theft of $50 intensified with heavy-handed questions that implied her guilt.

As the girl sat there sobbing, issuing quiet denials, McCorquodale changed tactics and pretended to soothe her feelings. As his left hand gently stroked the back of her head, Bonnie said she saw her boyfriend’s face change and she knew what was going to happen next; McCorquodale drew back his fist and smashed Donna in the face. After that, McCorquodale and Leroy began to slap, punch and hit the girl as they got her down to the floor.

Because of all the noise, the young couple’s roommate, Linda, woke from the back bedroom where she was sleeping with Bonnie’s three year-old daughter. Together, Bonnie and Linda watched and did nothing as McCorquodale and “Leroy” tortured the poor girl over the next couple of hours. First, they tied her wrists with Bonnie’s nylons, and then they started slapping and punching her, while denigrating her for associating with a black man and not “staying with her own kind.”

To keep her screams from reaching the neighbors, they put a washcloth in her mouth and secured it with electrical tape. McCorquodale then pulled off his leather belt that included a large, Western style buckle, and began whipping the girl with it.

Then, they ripped off her clothes.

Now that the young victim was nude, gagged, and bound, the torture began to escalate with cigarette burns, and hot wax from a red candle that was dropped on her stomach and private parts. The two men then took turns raping her orally, vaginally and anally. Afterward, the girl’s genitals were mutilated with chemicals and scissors.

As Bonnie told her story in a calm manner, the detectives were sickened by what they heard. After the rape and mutilation, Donna’s torturers took a break and released the girl to go wash up in the bathroom. By now, the three year-old had awakened and was put back to bed with a story that Timothy and Bonnie were helping a kitten who had a broken-leg. Linda would later claim she remained in the bedroom with the little girl and didn’t see what happened next.

In the living room, McCorquodale and Leroy discussed killing Donna Dixon. Timothy told his girlfriend to get a rope and she gave him a thin length of clothesline she recently purchased to hang in the bathroom.

After being coaxed out of the bathroom, and then a closet where she hid, McCorquodale pounced on her from behind and began to strangle her. At this point, Bonnie said, she told Leroy to get her boyfriend off of the victim or else he was going to kill her. It took both of them to pull McCorquodale off the dying girl.

As they looked down at her, the unconscious girl began to go into convulsions and her eyelids fluttered open and shut—indicating to her torturers she was still alive, but barely. It would have been the perfect time to call an ambulance but Bonnie, Linda and Leroy submitted to Wesley who was intent on destroying Donna’s innocent life. “Still tense with maniacal cruelty, the wiry McCorquodale threw himself upon her again, straddled her body, and choked her to death.” As he did so, he apparently slammed her head up and down and up and down, which eventually broke her neck.

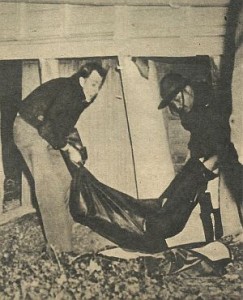

Now the foursome had a real problem, getting rid of the body. To get Donna’s battered corpse out of the apartment, they found a cardboard trunk which once contained the toys and clothes of Bonnie’s little daughter To get his victim inside the small box, McCorquodale had to stomp down on her arms and legs to break her bones. When witness Linda Deering later told police what it sounded like, she said “it was like you had taken a big stick and jumped on it, a cracking sound.”

McCorquodale voluntarily gave a written statement to police that was similar to Bonnie’s, but included information on how he had gotten rid of the body and some of the evidence. The day after the murder, McCorquodale and his girlfriend took a bus back to The Strip where he found a friend with a van who agreed to help him dump a box of trash by the side of the road. McCorquodale fiercely claimed his friend did not know what was in the box until they dumped it and refused to give police the man’s name. Because he was the decent type, McCorquodale claimed he got rid of it by the side of the road “so that it could found.”

As hard as they tried, police could not learn the identity of “Leroy” who was new to The Strip and whose last name was unknown. Bonnie and Linda did not know his last name and police could find no one on the street who even knew who he was. It was assumed that after the murder, “Leroy” left town and he was never caught.

Back at the apartment on Moreland Avenue, police found the victim’s blood in the carpet and on the tiles in the closet where she tried to hide. In the dumpsters, they found two white trash bags that contained her clothing, jewelry, purse and an address book with her parents Newport News address written inside.

On February 6 McCorquodale was indicted for first-degree murder and his trial took place in April in an Atlanta courtroom. His defense attorney eagerly tried to plead his client guilty, but Judge Osgood William would not accept saying he “could not, under any circumstances, sentence someone to death.”

To relieve himself of this burden, Judge Williams said he was rejecting McCorquodale’s guilty plea and forced the case to a jury trial where his punishment would be determined by twelve men and women. In spite of his unwillingness to sentence a man to death, Judge Williams noted that if McCorquodale was sentenced to death, it would be more beneficial for the higher court to have trial transcripts, as well as a decision that came from a jury.

In his opening arguments, McCorquodale’s defense attorneys told the jurors, “We’ve been trying to plead guilty for two days. Ladies and gentleman, we’re guilty. It’s that simple. We don’t deny what the witnesses are going to say.”

And what the witnesses, investigators, and experts had to say was revolting.

“The jury of six men and six women grew paler and paler as they listened to the medical man testify,” Richard Devon wrote for his article in Official Detective Stories magazine. “In truth, the evidence was enough to turn the stomach of any normal person, and numerous spectators, sickened, left the court room. Much of the evidence is unprintable.”

During the trial, both his girlfriend Bonnie, and roommate Linda Deering testified against him. When he was questioning Bonnie about the victim’s strangulation with the clothesline cord, assistant district attorney Melvin England stopped the flow of sickening testimony to ask her a simple question.

“Back up, just a minute, let me ask you—at the time the defendant put the cord around Donna’s neck, did she say anything?” England inquired.

Just as calmly as she had testified all day, Bonnie told the court: “She said, ‘Oh my God, he’s going to kill me.’”

For a good part of the two day trial, the jurors were sickened by not just what the women said, but how they said it. They were calm and unemotional on the witness stand with no affect in their voice or body language. Later on, Bonnie told the jury of a cold blooded telephone call she received at work from Linda.

Dearing called Bonnie and informed her, “That the victim’s body was smelling up the apartment and to tell McCorquodale to come and get it.”

Dearing also had the unusual task of keeping Bonnie’s three year-old daughter away from the cardboard box that was shoved into a closet which had a cloth curtain instead of a door. It was the same closet Donna Dixon had tried to hide in.

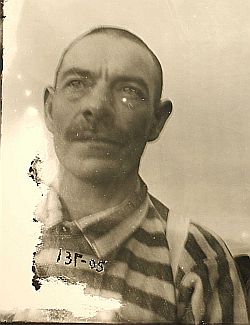

After a ninety-seven minute deliberation, Timothy Wesley McCorquodale was convicted on April 12 and sentenced to death. In December of 1974, the Georgia Supreme Court denied his appeal. However, McCorquodale, along with all other death row inmates, were granted an indefinite stay of execution by Governor and Presidential candidate, Jimmy Carter, as the death penalty issue was revisited by the United States Supreme Court in 1976.

By sheer luck or miracle, McCorquodale’s execution date was continually put off until the 1980s. In May of 1980, McCorquodale and three other Georgia death row inmates wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter with an offer to go on a military mission to rescue the fifty-two American hostages held by Iran at that time.

“All four of us have discussed this proposition and we would rather go to our graves fighting for our country than sitting here and rotting in this hell,” wrote famed mass-murder Carl Isaacs. Isaacs killed six members of the Ned Alday family in 1973.

Although their letter was published in newspapers, President Jimmy Carter never wrote back. For Isaacs, it was another one of his many publicity stunts. The three other prisoners that were to accompany him on their secret mission were Timothy McCorquodale, Troy Gregg, and Johnnie L. Johnson.

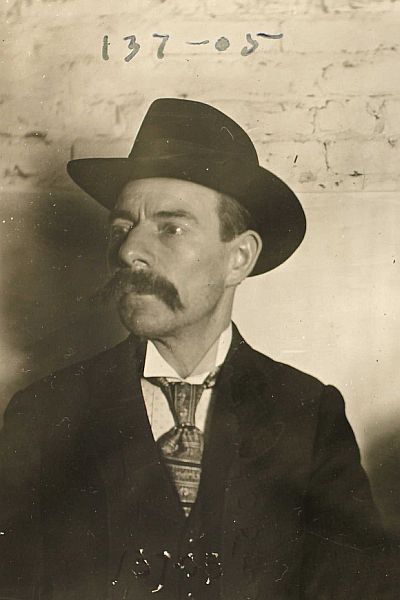

Two and one-half months later, on July 28, 1980, McCorquodale, Gregg, Johnson and David A. Jarrell escaped from a maximum security prison at Reidsville, Georgia. Using hack saw blades smuggled into prison with the approval of a corrupt guard, the four death row inmates sawed through the bottom bars of their cell doors. Then, at 6 a.m., they just walked out of the prison wearing re-tailored pajamas dyed black and made to look like guard uniforms. Although they were scrutinized at the main gate of the 2,100 inmate prison, the fake uniforms were enough for them to bluff their way through. The accessories and patches sewn into the phony uniforms came from the corrupt guard who had been selling drugs to prisoners.

One hour later, Gregg telephoned Albany Herald newspaperman, Charles Postell, and told him of their escape and said they were in Jacksonville, Florida. When Postell called deputy commissioner Col. William Lowe to inform him of the escape, Lowe later told reporters it was the first time he had heard about it.

“Their flight from fourth floor cells was so well executed that more than hour after Postell informed prison officials of the ‘news tip,’ the escape had not been confirmed,” the Associated Press reported.

Three of the prisoners were captured two days later inside of a rundown house near a lake in North Carolina following a six hour stand-off with police that included a helicopter hovering overhead. The house was owned by William “Chains” Flamont, a member of the motorcycle gang the ‘Outlaws.’ Flamont said he was friends with escapee Jarrell, and news reports at that time indicated McCorquodale may have been a member of the Outlaws when he murdered Donna Dixon. Also in the house at the time was James Cecil “Butch” Horne, a close friend of Flamont’s, who also may have been a member of the Outlaws.

Although police wouldn’t say what tipped them off, before the stand-off they retrieved Gregg’s body from a nearby reservoir. Flamont told police a fight erupted between the prisoners and Gregg was beaten to death. Later reports indicated McCorquodale was the key individual behind Gregg’s murder.

After the prisoners were returned, eleven individuals were indicted with helping the four death row inmates escape. This included McCorquodale’s mother and aunt who investigators said sent him the hacksaw blades concealed inside the handle of a portable radio. Investigators also reported McCorquodale’s mother, Toni Jo Hooper, and Aunt, Minnie Hunter, visited the prison the day before the escape and left a car with the keys inside waiting in the parking lot for the four to drive away in after their escape.

Besides a prison guard, authorities also indicted Charles Postell and his wife who they said purchased the hacksaw blades. Postell vigorously denied these charges with the declaration that Georgia authorities were trying to get revenge on him for publicly embarrassing him. The hardware store attendant, whom Georgia investigators claimed sold the hacksaw blades to Postell’s wife, could not remember the purchase.

“We are inclined to view it all as harassment and revenge,” Postell’s boss at the Albany-Herald told reporters on August 28, after his employee was released on $5,000 bond. “Certain law enforcement agencies got egg on their faces.”

The outcome of the eleven indictments is unclear from available newspaper archives. If the hacksaw blades were smuggled in a portable radio purchased by members of McCorquodale’s family, it would be completely unnecessary to have someone else purchase the hacksaw blades.

During a preliminary hearing for “Butche” Horne, another witness testified: “That McCorquodale knocked Gregg down and began stomping him. He said McCorquodale, who is six-foot three-inches tall and weighs about 300 pounds picked up his right foot and stomped down with all his weight several times on Gregg’s upper chest, throat and head.”

Butch Horne then pushed McCorquodale off and stomped on Gregg himself, the witness said in court. In spite of this testimony, officials chose not to charge McCorquodale or Horne with the murder of Gregg.

McCorquodale’s appeals dragged on for seven more years with the help of an attorney from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Besides alleged errors made during his 1974 trial, McCorquodale’s various appeals claimed that he told a state psychiatrist in 1976, who believed him, that he could not remember murdering Donna Dixon.

”I cannot believe that I would do them things,” he claimed during a session. ”I just don’t believe I could do it.”

In the year leading up to his execution, those who knew him said that Donna Dixon’s killer, now in his mid-thirties, underwent a religious transformation. In a last bid to stay alive, McCorquodale wrote a letter to the state pardon and parole board. The board chairman then told reporters “he does show considerable remorse for what he’s done.”

But it was too little, too late and Monday, Sept. 21, 1987 McCorquodale’s legal luck ran out and at 7 p.m. he was strapped into the state’s electric chair. In a 1990 article, newspaper reporter Amy Wallace recalled the time she witnessed McCorquodale’s execution.

Placing both his hands on the armrests, the six-foot-one-inch, 270-pound inmate hoisted himself into the electric chair that inmates had built out of sturdy Georgia pine.

As usual, there would be no single executioner. To spare any individual the job of killing, the state had divided each electrocution into dozens of tasks, and prison employees were asked to volunteer for just one. On this day, dozens of people would perform the many rituals that, altogether, would lead to McCorquodale’s death.

Earlier that afternoon, one guard had served him his last meal: boiled shrimp, crab legs, tossed salad with Thousand Island dressing and apple pie à la mode. Another prison official had tape-recorded a private statement that would be stored in the prison archives, and the prison barber had shaved McCorquodale’s head.

Now, six guards surrounded him. In a carefully choreographed procedure, they fastened ten leather straps around McCorquodale’s body, cinching them tight. The guards exited and a prison electrician attached two electrodes to wet sponges at the top of the inmate’s head and on his right ankle.

Before the leather hood was placed over his head, McCorquodale was asked if he had any last words. With a thumbs-up to his father, cousin, and two other family members, McCorquodale said, “Yes, I would like to tell my dad, and everybody with him, that I love them very much. Stay strong in Christ.”

At 7:23 p.m. Eastern time, thirty-five year-old Timothy Wesley McCorquodale was pronounced dead. Donna Marie Dixon would have been thirty-one years old.

[1] State Route 42 and Highway 23 now run concurrent with each other near Slate Road, Clayton County, GA.

Here is a link to an audio recording of his execution.

Bibliography

“State Murder Trial Continued Despite Plea,” United Press International, Pulaski Southwest-Times, Pulaski, VA, April 12, 1974, page two.

“Incredible Torture-Murder by a Southern Sex Sadist!” by Richard Devon, Official Detective Stories, August, 1975.

“Condemned Await Supreme Court: Re-evaluating the Death Penalty,” United Press International, The Argus, December 1, 1975, page two.

“3rd Man’s Execution Date Set,” Associated Press, Thomasville Times Enterprise, October 26, 1976, page ten.

“Gilmore Wins Plea for Execution; Pardons Board Orders Date Set,” John Nordheimer, New York Times, Dec. 1, 1976, page forty-nine.

“Inmates Volunteer for Hostage Rescue,” Associated Press, Logansport Pharos-Tribune, May 11, 1980, page two.

“Killers Flee GA. Prison,” Associated Press, Winchester Star, July 29, 1980, page one.

“4 Killers Flee,” Associated Press, The Daily Globe, July 30, 1980, page twenty-two.

“Fugitives Holed Up for Six Hours before Surrender,” Associated Press, Elyria Chronicle-Telegram, July 31, 1980, page one.

“Jury Indicts Three after Jail Escape,” Indiana Evening-Gazette, August 14, 1980, page three.

“Evidence Lacking for Murder Trial in Escapee’s Death,” Associated Press, The Sumter Daily-Item, August 26, 1980, page one.

“Editor Indicated on Escapes,” United Press International, Marshall Evening-Chronicle, August 28, 1980, page eight.

“Appeal Challenges Death Jury,” Associated Press, The Harrisonburg Daily News-Record, August 31, 1982, page nine.

“Slayer Executed in Georgia; High Court Rejects Appeals,” Associated Press, New York Times, September 22, 1987, page A24.

“Commentary: States Using Death Penalty Must Not Look Away,” Amy Wallace, Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1990.

—###—

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, August 27th, 2014 under Feature Stories.

Tags: 1970s, Execution, Georgia, Murder, Psychopath

Comments: 1