This story was written by NYPD detective Captain Henry Flattery, Retired, for Front Page Detective magazine, November, 1955. It was part of a collection of stories called, “Dumbells I have Known.” which poked fun at some stupid criminals. He was with the NYPD for thirty years and worked on many important cases from that time including the still famous Ruth Snyder – Judd Grey case. – At the bottom is a link to another nice feature story about the case.

Sometimes a man who murders in haste is smart enough to realize that all the signs are going to point to him, so he tries to cover up by planting misleading evidence or incriminating someone else. But time is always working against him and he invariably bungles the job. At best, he gains only a few extra hours of freedom. Here is a good example of that:

During World War II, there was a man we called the “Cupcake Killer.” He got an unexpected break when his victim inadvertently threw suspicion on another man. In spite of that, and in spite of the Cupcake Killer’s clever ruse to throw us off, he was arrested within 24 hours. He had killed in an angry frenzy and left a calling card.

On a cold winter night in 1942, Patrolman Joseph Doyle was walking past the Dutch Reformed Church in Queens when he saw a light flicker in the dark churchyard. For a moment he stared into the blackness, wondering if he could have been mistaken. Then the light flared again. Doyle jumped the fence. Instantly the light died and there was the sound of running footsteps up the gravel drive. Doyle searched the area with his flashlight but could find no one.

He went back to where he had first seen the beam of light. No windows were broken in the church. There was no indication that anyone had tried to break in. Then Doyle saw the woman. She was lying just off the path. A green scarf was tightly knotted around her throat, which had been viciously slashed. She was young and had been pretty once. Now she wasn’t.

Ten minutes later, the churchyard was filled with policemen. Searchlights were set up and the medical examiner began inspecting the body.

As I listened to Officer Doyle’s story, it struck me that the killer must have lit some matches after the woman was dead: he wouldn’t require any light to strangle her or cut her throat, and even if he did she’d be unlikely to hold still while he used his hands to light a match. That being the case, the killer must have been looking for something, her purse if he was a mugger, something that belonged to him if he wasn’t.

“Cover every inch of the yard,” I instructed my men. “I’m looking for a calling card.”

But, except for a bakery carton of cupcakes, nothing was turned up. There were no signs of a struggle.

The medical examiner made his report: “She probably died a few minutes before Doyle spotted her. Strangled with the scarf. Those cuts are funny. Not one big one but a whole series of little ones, as if the killer had used a small knife. And not a very sharp one at that. No matter. The scarf’s what killed her.”

By this time, a crowd had gathered outside the churchyard although it was almost 2 a.m. Hoping to get a lead on the dead woman’s identity, I asked them to file by and have a look at her. They did, but it brought no results.

Back at headquarters, I went through a pile of Missing Persons reports. There was nothing matching a description of our murder victim. It seemed to me that if the woman had been carrying a box of cupcakes, she might have a family. But if she had a family, why hadn’t they reported her missing?

Other things weren’t adding up, either. The case didn’t follow the pattern of the usual muggings. Muggers didn’t use scarves, they used their forearms. And they certainly didn’t hack away at their victims’ throats with a dull knife. They weren’t interested in killing, only in stealing. They’d kill if they had to, but they wouldn’t stop to cut someone’s throat after they’d gotten what they wanted by strangling.

No, it looked like our killer had planned on murdering the girl, then tried to cover up by making it look like a mugging. If that was so, whatever the killer was looking for in the darkness must have belonged to him—and must be important to us.

Now a clearer, more logical picture began shaping up. The girl had entered the churchyard with the killer. She knew him.

At 4:30 that morning, a patrolman found the victim’s purse five blocks from the churchyard. It matched her outfit and contained identification papers and a commutation ticket to Freeport, Long Island. We phoned Nassau County police, outlined the crime and asked for a check on a Carol Dugan of Freeport.

Meanwhile, another discovery had been made. In the churchyard, detectives had uncovered the calling card I was hoping for; a small, bone-handled knife. It still had blood on it.

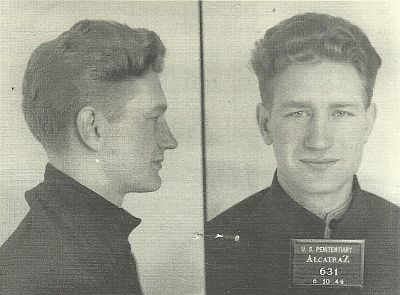

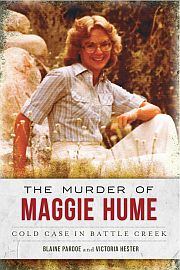

Victim Carol Duggan Tuttle

By morning, we had the report on the victim. Her name was Carol Dugan Tuttle. She worked in a large chain store not far from the church. Her husband was on his way to police headquarters.

Now things began to move quickly. Tuttle, obviously shaken by his wife’s death, answered all our questions forthrightly.

Why hadn’t he notified the police when his wife didn’t get home by, say, midnight?

“She stayed out late pretty often. I thought she’d missed the last train. I had to put the kids to bed. Then I went to bed myself.”

Did he know of anyone who might want to kill her?

“Yes. That is, someone tried to kill her a couple of weeks ago. She came home about six in the morning, all beat up and cut. She said a sailor named Wright, John or Joe Wright, who used to work in her place had done it. She promised me she wouldn’t fool around anymore.”

At a tavern near the churchyard, one of several we had been checking, we began unfolding the mystery of Carol’s last hours. She had been there the evening before, drinking with a man the bartender knew only as ‘Jim.’ The bartender remembered the box of cupcakes.

“Was Jim a sailor?”

“No, a civilian.”

A check of the store where Carol had worked turned up a youngster who knew Jim well: “He’s James Mallon. Used to work here. He and Carol were sweet on each other.”

“Do you know a John or Joe Wright?”

“No.”

By now, I was convinced that the killer had tried to throw us a curve ball by making the murder look like a mugging. The question that remained, therefore, was which of Carol Tuttle’s after-hours friends, Mallon or Wright, was our man. We tried Mallon first.

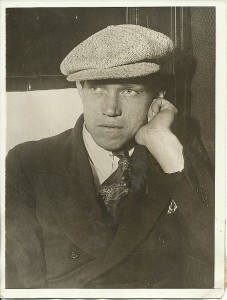

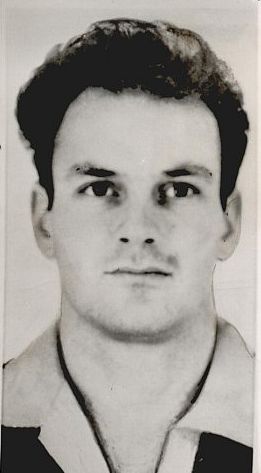

A tall, rawboned young man, he was shocked when we told him Carol was dead.

“But I was with her last night,” Mallon exclaimed.

“Yes, we know. Let’s hear about it.”

“Well, we went to this tavern where we always used to meet. We had a few drinks and talked. About midnight or a little after, we left. Carol went to the railroad station and I came home.”

“You didn’t walk through the churchyard with her?”

“No.”

“Do you know a sailor named Wright?”

“No.”

“What about Carol’s husband? Know him?”

Now Mallon looked even more shocked: “What do you mean, Carol’s husband? She’s not married. She was going to marry me.”

We took Mallon to headquarters, then began checking Carol’s friends in Freeport. We hit pay dirt with the first one, a girlfriend, who remembered the time Carol had been beaten.

“She came to my house before she went home that night,” the girl explained. “She said she was afraid to let her husband see her like that. I persuaded her it was best to face the music so she went home.”

“Did she tell you who did it?”

“She didn’t have to. I know this Jim Mallon she goes with. He has a terrible temper.”

“What about the sailor, Wright?”

The woman shook her head. “I don’t know of any sailor.”

James Mallon talking to a NYPD detective. He might be Cosmo Kramer’s father.

We went to work on Mallon but he insisted that he had left Carol shortly after midnight, that he had never known she had a husband and three children by a previous marriage. Then came the big break, a letter we found among Carol’s things. It was from Mallon and it read: “I know you are thinking of the children, but you don’t owe Harry anything.”

It was pretty clear now. Afraid to tell her husband about Mallon, Carol had invented the sailor named Wright—someone Tuttle could never check up on because he didn’t exist. As for Mallon, he was acting the injured innocent because if he could convince us that he didn’t know about Carol’s husband, he would have no motive for killing her. The letter made a liar out of him and a killer, as well. He had beaten Carol up because she wouldn’t leave her husband for him and he had murdered her for the same reason.

We were ready to play our ace. Calling in witness after witness, we showed them the little bone-handled knife we found in the churchyard and asked if they recognized it. Every one of them who knew Mallon identified it as the one he always carried on his key chain. Result: we had placed Mallon in the churchyard in contradiction to his statement; we knew what he was looking for when he lit the matches.

Caught dead to rights, Mallon finally confessed to Carol Tuttle’s murder and was given a 20 years to life sentence. He had gotten every break a killer could ask for: a phony suspect, a misleading motive and a chance to get away unseen. But he had stacked the cards too high against himself. He had killed in haste; he got plenty of opportunity to repent at leisure.

Further Reading: “Murder in the Church Yard,” by Edward Radin, Milwaukee Sentinel, July 10, 1955, pages 31 and 32.

—###—