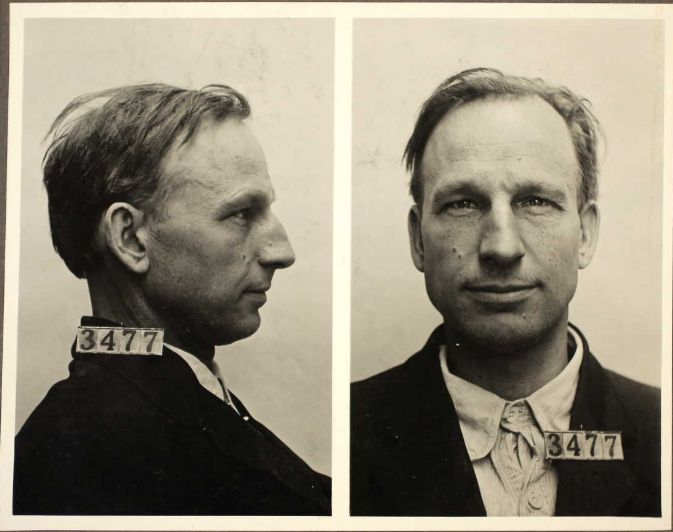

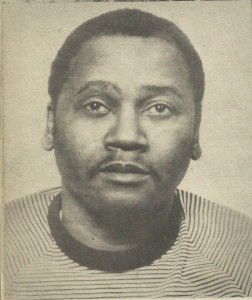

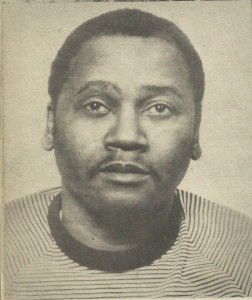

Serial Killer James Turner

James Turner is an almost entirely unknown suspected serial killer linked to the murders and ‘accidental deaths’ of seven friends, coworkers, and family members in which he was the beneficiary of their life insurance policies. He was active for a twelve-year period between 1963 and 1975, when he was arrested on January 22 for the machete murder of his twenty-year-old brother-in-law, Dwight Dee s, near Rochester, New York. He was indicted on February 27 in Monroe County Court and pleaded not guilty on March 3.

s, near Rochester, New York. He was indicted on February 27 in Monroe County Court and pleaded not guilty on March 3.

Below is just a brief article I put together about the murders he was a top suspect in. He was later convicted of murdering Dees and sentenced to twenty-five years at Attica prison in New York.

Victims

Victim One: Sometime in June 1964, a coworker of Turner’s from the Nabisco plant in Rochester disappeared and was never found. John Louis Brown’s $5,000 life insurance policy named Turner as the beneficiary. It is unclear if Turner collected on this policy since there was no body to prove that Brown was dead.

Two: On November 19, 1968, Frank Scialdone, eighteen-year-old coworker of Turner’s at the General Motors plant in Rochester, was found murdered. The boy’s family members reported that James Turner was going to co-sign a car loan for Scialdone, who was set to buy a life insurance policy to cover the loan in case he died. However, Scialdone was found with a bullet hole in the back of his head before he could take out the policy. On the day he was killed, relatives say he had $400 on him which he was going to use towards the purchase of the car.

Three: In May 1969, the partially decapitated body of William Bradwell was found floating in the Genesse River. Shortly before his death, the twenty-three-year-old GM employee named Turner as the beneficiary of his $5,000 life insurance policy. In that case, it was confirmed that Turner actually collected on the policy.

Four: On December 2, 1969, Lewis McDowell, 29, was found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning in his garage. He was listed as a suicide. Shortly before his death, he changed the beneficiary on a company life insurance policty to coworker, Jim Turner.

Five: In July of 1971, GM employee Horace Everett changed the beneficiary on his $9,000 life insurance policy from his wife’s name to James Turner. Mrs. Everett would later tell newspaper reporters that during those summer months, her husband and Turner held many secret meetings at their home. She didn’t know what he was up to, but realized it must be bad and begged her husband to back-out of whatever plan he and Turner had concocted.

“I told Horace that whatever they were up to, it was wrong,” his wife said. “I told him it was wrong because of the children. But he said that’s why he was in it, whatever it was. He said he loved the children and wanted to make life easier for them.”

Everett refused to back down and told his wife that he would be meeting with Turner the following day and they would soon be rich. He never came home that night and his body was found the next day behind an abandoned factory.

“A terrycloth towel was wrapped around his head, and, when it was removed, police discovered that the right half of his skull had been blown apart with a shotgun,” wrote Joseph Koenig in a June 1975 issue of Inside Detective. He left behind three small children and a fourth who was born two months after he died.

With their suspicions raised, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company refused to pay James Turner after their investigation revealed that the change in beneficiary was “improperly and fraudulently procured.” Everett’s wife received $6,750 as the co-beneficiary as well as an additional $4,500 from an accidental death clause.

Although insurance investigators and police looked upon him with suspicion, Turner had the audacity to sue the life insurance company and fight with Everett’s widow in court. However, by 1973, he dropped the lawsuit when too many uncomfortable questions were being raised about the death of Horace Everett and his possible motive and connection in the case.

One month before Everett’s murder, Turner moved his family into a two-story, three bedroom Colonial house that was built to his specifications in a new subdivision. He and his wife decorated the $40,000 home ($233,000 in 2014) with new furniture.

During his court battle with the insurance company, Turner’s brother-in-law, Dwight Dees, moved into the home and attended community college. In the fall of 1974, Dwight mysteriously resumed the premium payments on a $50,000 life insurance policy he had previously dropped when his education expenses became too great.

Six: On January 21, 1975, a borrowed car Dwight was driving that night was found nose-down at the bottom of a twenty-foot embankment. Inside, lawmen found Dwight’s body with his head nearly decapitated. While searching the area, investigators located a blood trail which led to several large pools of blood behind an old barn several hundred feet away. It was obvious to them that someone nearly cut off the boy’s head behind the barn and then dragged the body back to the car in order to make it look like an accident.

The investigation quickly led police to James Turner who was arrested on suspicion of murder the following day. Following his arrest, an insurance agent saw the news on television and called police to report that their suspect had 50,000 reasons to kill his wife’s youngest brother. A few days later, police located a machete which Turner had used to hack away at the young man’s neck.

An all-out investigation by police soon uncovered the insurance connections between Turner and the deaths of Brown, Scialdone, Bradwell, and McDowell. When it came to Horace Everett, Turner was already the number one suspect, although police couldn’t prove it.

Seven: When authorities dug a little deeper, they learned that Turner collected $2,500 on two life insurance policies after his sister suffocated to death during a tragic fire in her apartment on April 14, 1963. At the time, James lived with her, but was not at home when the fire began. He filed to collect her benefits the day after she died. The files from that death showed Turner had called the insurance agent several days before the fire to cancel his own polices, and to double check that his sister’s policies were still active. Also, at that time, Turner worked in a hospital where police speculated he may have stolen pills that he used to drug his sister before he set the fire and left.

Turner and his family were originally from Florida and when police looked into his time there, they learned from family members that another sister of his was murdered near Plant City in 1954. When Rochester investigators asked Florida police to check their records, however, they could not locate any files on the twenty-year-old murder. [Note: From research I did after this story was written, it appears this sister died from a knife-attack by another woman who was convicted and sent to prison].

Family members also told police about two other Florida relatives who died in what were then believed to be accidents. But now, they weren’t so sure.

When police interviewed neighbors and coworkers, they learned Jim Turner was an extremely hard working man who was friendly and considerate with everyone who lived on his street. He would use his snow blower to clear the sidewalks for neighbors, who were unable to clear it themselves. They also recalled he was a strict father who cared deeply about the welfare of his children and never drank heavily or chased other women. He usually went to bed early so he could wake up early to work long hours.

After Turner pleaded not guilty, the judge ordered him held without bail. No further information on his case exists. I imagine more could be found by searching the microfilm of local newspapers at the Rochester Public Library, but with no dates to search under, it would be a tedious process that would require the researcher to read every single newspaper for the remainder of 1975. Further information might be obtained from police or prison records, and possibly, FBI records.

Update: June 18, 2017: I have recently obtained access to Rochester, New York, newspapers which covered his trial. I hope to finish this article soon.

Here is a link to one of the few articles available about James Turner.

—###—