During the late evening hours of October 4, 1919, a shepherd tending a flock east of Seligman, Arizona, discovered the smoldering, badly burned body of a man behind a small hill located one hundred feet from the transcontinental road known at the time as the National Old Trails Road. The following day, he reported the find to his employer who then notified authorities.

When Yavapai County lawmen investigated the scene, they determined the victim had been shot in the back, wrapped in a blanket, dragged behind the hill, and set on fire in attempt to obscure his identity.

Although the clothing was nearly destroyed and the body charred and unrecognizable, authorities found a Canadian military button with the serial number “400754” and determined the unknown male was wearing his Canadian uniform when he was killed. Inside of his puttees, that were tightly wrapped around his ankles and calves, (the easily identifiable hallmark of American and Canadian soldiers during World War I), they found $60 the murderer had missed.

With no identification and only the serial number on the button to go on, Arizona authorities wired the Canadian identification bureau which checked their records and reported that a button with that serial number on it was issued to Arthur De Steunder. According to his Canadian military records, De Steunder had stated that his family lived in Chicago, but he listed no address for them.

With no identification and only the serial number on the button to go on, Arizona authorities wired the Canadian identification bureau which checked their records and reported that a button with that serial number on it was issued to Arthur De Steunder. According to his Canadian military records, De Steunder had stated that his family lived in Chicago, but he listed no address for them.

Undeterred, Chicago authorities ran advertisements which appeared on movie screens throughout the city. This quickly led to the location of several of De Steunder’s family members, including his wife who was in the process of divorcing him.

De Steunder’s sister-in-law described to a Chicago Daily Tribune the peculiar circumstances by which he had recently left Chicago.

“He answered an advertisement about a month ago and met a man who offered him $10 a week and expenses to make a car trip throughout the western United States,” his brother’s wife reported. “The purpose of the journey was kept a mystery. They spent several days getting ready in Chicago and then departed. We didn’t like the man’s looks. Arthur’s sister met this man and warned Arthur against going.”

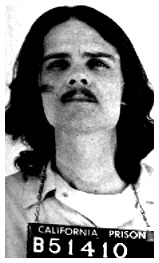

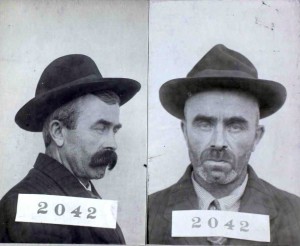

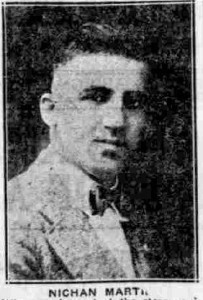

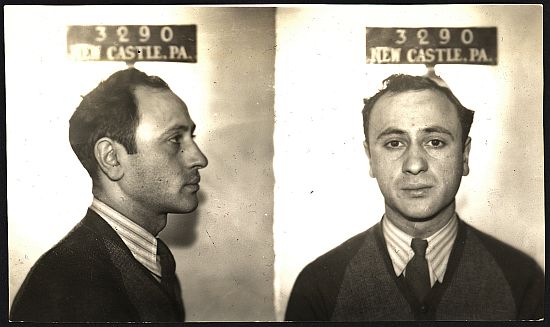

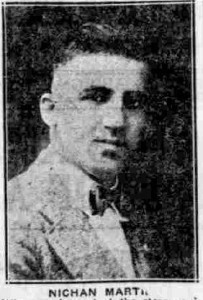

The man who placed the newspaper ad was Nichan Martin, a twenty-five-year-old Armenian immigrant from Turkey who had immigrated to the United States in 1912, and fortified his American citizenship by volunteering as a soldier during World War I.

By interviewing business proprietors along the continental road that stretched through Holbrook to Kingman, near the California border, investigators found witnesses who had seen the two men travelling together. On September 25 both men were arrested near Holbrook and held in jail for observation after a local store was robbed. They were released a few days later for lack of evidence. According to observers, Martin’s face was unforgettable because of his oddly shaped cranium, and a crimson port-wine stain on his cheek.

On the night of October 4, Martin had registered at a local hotel and signed his name, hary Diyer (sic), a clear sign to others the strange man didn’t know how to spell an alias he was trying to use to some unknown advantage. [Common enough first and last names that should have been spelled Harry and Dyer.]

hary Diyer made quite an impression on hotel guests and employees by telling anyone who would listen, and even those who didn’t want to listen, that he had made the journey from Rhode Island in his Hudson automobile alone, and that he could find no one who wanted to travel with him.

“Martin’s talk around the Kingman hotel, according to witnesses, all centered about the impossibility of getting a companion for his long automobile ride across the country, and his standing offer to take anyone along who would pay for the fuel and oil for his machine,” a Prescott weekly newspaper reported. “It is said that his insistence on this topic created some talk among the Kingman hearers, who wondered why the traveler should have found it so difficult to pick up a companion.”

With Kingman located only sixty miles west of where the body was found, authorities calculated that Martin murdered De Steunder sometime during October 4, possibly during the early morning hours. The body was then found later that day by the shepherd.

After he left Kingman, Martin travelled to his home in Yettem, California where detectives tracked him down. He was arrested on October 15, just nine days after De Steunder’s body was first discovered. Besides the victim’s Hudson Six automobile, Martin was also in possession of De Steunder’s luggage, military discharge papers, and a bravery medal. Despite having these items, Martin claimed that he and De Steunder had parted company near a small town 100 miles east of Prescott, Arizona, and that he had not seen him since.

After he left Kingman, Martin travelled to his home in Yettem, California where detectives tracked him down. He was arrested on October 15, just nine days after De Steunder’s body was first discovered. Besides the victim’s Hudson Six automobile, Martin was also in possession of De Steunder’s luggage, military discharge papers, and a bravery medal. Despite having these items, Martin claimed that he and De Steunder had parted company near a small town 100 miles east of Prescott, Arizona, and that he had not seen him since.

As Martin was being transported by rail to the county jail in Prescott, Arizona, he was able to escape near Needles when the train stopped to allow passengers to dine in a railroad affiliated restaurant. Since it was evening, and the countryside was wide open desert, Sheriff Warren Davis postponed tracking him down until morning, but telegrammed nearby lawmen, railroad personnel, and several local men’s groups to be on the lookout for Martin.

With the help of a local expert tracker, Martin was easily located the next morning twelve miles west of town near the railroad tracks with a bullet in his buttock. He claimed he had been shot by members of the Santa Fe train crew. When the train crew was questioned, they claimed it was an automobile party traveling along the highway near a point where the tracks and the road run parallel.

It was never made clear who actually shot Martin, and from newspaper reports, the authorities didn’t seem to care.

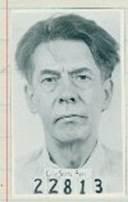

Martin went on trial in Prescott on March 25, 1920. Four days later, he was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang. His court appointed attorney filed an appeal which was eventually denied by the state supreme court and an execution date was set for June 10, 1921. Through legal motions in state courts that were all denied, Martin’s execution was pushed to Friday, September 9, 1921.

In his final days, Martin was calm and resigned to his fate. At what was probably two or three o’clock in the morning that Friday, Martin was awakened in his death cell at the state penitentiary in Florence, Arizona, and served a hearty breakfast which he ate.

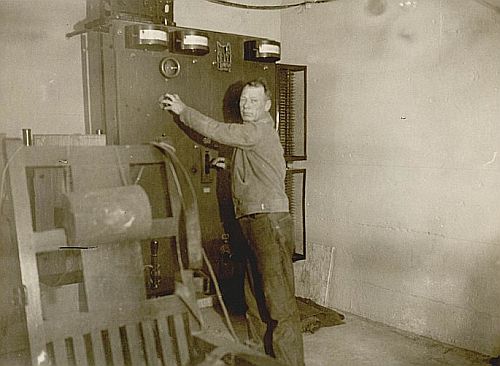

At five o’clock, Warden Thomas Running appeared at his cell to read the court’s death mandate. Martin was then blindfolded, and led to death chamber where he mounted the steps to the scaffold with ease and took his place over the trap door.

“Straps were placed about his legs and arms and then Capt. Thomas H. Rynning, superintendent of the prison, asked Martin if he had anything to say.

“I am the happiest man in the world,” Martin replied in broken English. “Best regards to everybody, good-bye.”

The prison chaplain embraced the condemned man and bid him good-bye. The black hood was then adjusted and the trap sprung at 5:08. Martin hung there for a full twelve minutes before the prison physician pronounced him dead. He was buried in the prison cemetery.

Several weeks after Martin’s death, an Arizona newspaper confirmed that the two men were financing their excursion across the Southwest by robbing businesses along the way. Martin may have murdered De Steunder over a falling out regarding the spoils of their crimes, or to silence him.

—###—