Full Story: I was a Killer’s Captive, 1954

Editor’s Note: In 1954, Mary Ruth Rombalski was a nineteen-year-old girl from Kentucky who, like many young girls from that era, dreamed of moving to Hollywood where she would become a movie star. After leaving her husband in Milwaukee (a marriage that never should have happened in the first place and he was glad to see her go, she says), Mary went from town to town working as a waitress, trying to save enough money to get a bus ticket to Los Angeles. In December, she was working in Brady, Texas where she met local loser and Army reject, Max (Red) Stapleton, also 19, who promised to take her to Los Angeles. Along the way, he robbed a liquor store in El Paso, and shot to death California gas station owner Orville Johnson, 55, during a hold-up. Mary, who was held captive for most of the journey, was able to escape from “Red” before he crossed the border into Mexico. She reported Red’s crimes to Nogales, Arizona police who arrested him on January 7, 1955. She was also arrested, held as an accessory, and both were transported to Kern County California, where Stapleton was indicted for first-degree murder. Her first person account of her life, and what happened during her time with Stapleton, was published in the May 1955 issue of Front Page Detective, which was placed in the public domain on Internet Archive.

By Mary Ruth Rombalski

Bakersfield, California, February 4, 1955

Originally appeared in Front Page Detective, May 1955

I don’t mind talking about it, really. Not anymore. Fact is, it helps me get the whole thing clear in my own mind. It seems like a bad dream.

That’s a funny thing, my mentioning dreams. I used to have nightmares when I was a little girl. You know the kind. I’d dream something terrible happened to mama, like maybe an auto accident. I’d wake up crying and it would seem so real that I wouldn’t get it out of my head. So I’d get up out of bed and walk barefoot into mama and papa’s room. Papa would be snoring like an outboard motor and mama would be sleeping peacefully beside him with her hair falling over the pillow. When my heart slowed down to normal, I’d slip in beside mama and snuggle up close. Sometimes I wouldn’t fall asleep for an hour, just hugging her tight.

What I mean is this thing that happened to me was like a dream, but everything was still all wrong when I woke up.

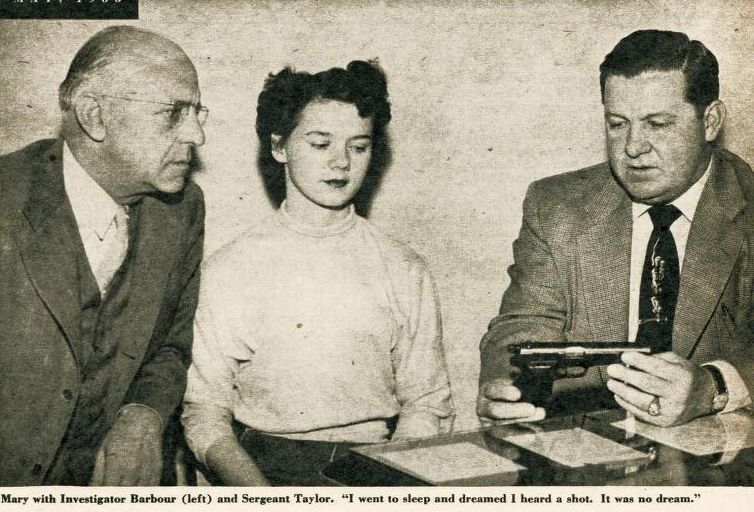

I went to sleep and dreamed I heard a shot. When I woke up it was no dream. There I was, smack in the middle of a murder.

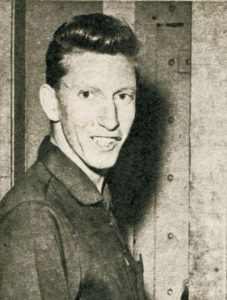

That’s why I’m here in the Juvenile Home at Bakersfield, Cal., a town where I have no friends or relatives. Oh, they treat me nice, all right. Sergeant Joe Taylor has been as sweet as he can be. So has Mr. Wooldridge, the district attorney. And my own lawyer, Sheldon Krasnow, has been just like a brother. They all know I’m telling the truth. I’m a material witness in that murder I mentioned: The People vs. Stapleton. That’s Red, a big, lanky, grinning, bragging, loud-mouth fellow from Brady, Texas. Him and his big talk! He’s the one that landed me in this hot water. And that poor little man at the filling station! It twists me up inside to think of it.

I don’t want you to get the wrong idea about me. On the record, I don’t look too good right now. “After all,” you might say, “she’s charged with murder, too. Same as Max Stapleton.” I call him Red, on account of his hair. But there’s a difference between me and Red. He’s been indicted by the Kern County grand jury, and he pleaded guilty to murder in superior court just yesterday, February 4, 1955.

I’m not under indictment. I am charged in municipal court, but that’s just what Mr. Wooldridge calls a technicality..

I’m going to testify against Red next week when Judge Howden decides whether it was first or second-degree murder when Red killed Orville Johnson. After that, I’ll be taking the bus home to my folks in Middlesboro, Kentucky, Papa’s going to get me a job.

I won’t be in any hurry to leave home again, I can tell you that. Not after what I’ve been through!

MY folks are honest, ordinary, hard-working people. I’ve got three brothers and a sister, all smarter than me. At least none of them ever got in a mess like this.

I’m 19 years old and five feet two inches tall. I weigh 115 pounds in my underwear. Of course, that counts ten pounds I’ve gained in the month I’ve been here. My figure—well, it’s right in the right places. I’ve got brown hair and brown eyes and a face I’m not ashamed of.

Let’s put it this way: I’ve been whistled at plenty of times; a lot of fellows have thought I was cute.

Red did at first. That was before he found out that I wasn’t the gun-moll hype.

I grew up in Tennessee and Kentucky, a small-town girl with romantic notions about excitement and opportunity in the big cities. Mama and papa tried to talk me out of that, but I didn’t listen. I was 18, tired of high school, tired of the boys at home and hungry for “independence.”

I landed in Milwaukee with one suitcase of clothes and almost no money. I had some ideas about modeling, but I had to settle for a job in a factory. I met my husband there. I’m not going to spend too much time on him. It’s all over between us. It shouldn’t have happened in the first place.

My husband wasn’t exactly a dream-boat, looking back at him. But he took me to dances and shows, and he was the nearest thing to romance I found in Milwaukee. Besides, he was a nice guy. So we got married.

I won’t bore you with the laundry list of things we fought about in our few months of marriage. Let’s just say that he couldn’t stand me and I couldn’t stand him. I finally gave it up as a bad job. I walked out. I think he was just as glad. I haven’t heard from him to this day.

The longest bus ticket I could afford put me in St. Louis. From then until almost Christmas, 1954, I was a gal on the move. I’d get a job as a hasher, save enough for another bus trip and pull up stakes. I was heading generally west.

I was like a million other not-bad-looking gals. I had California in the back of my mind. Hollywood, I guess. If you think I was nuts, I’ll be the first to agree.

Let me tell you one thing. Traveling and working like I did is the way to meet most of the heels in the U.S.A. I’d get a waitress job and it wouldn’t be two days before the boss was hinting I owed him small sex favors. You know what I mean. That would be the end of that job.

Soon as they find you’re single and away from home, you’re fair game for every Romeo on U. S. 66. Did I tell you I tried hitch-hiking a couple of times? The stuff I had pulled on me—oh, brother! After one or two of those rides, I made up my mind I’d walk to Los Angeles if I couldn’t afford the bus.

Well, I’d lost a lot of my romantic notions—but not all of them, unfortunately, by the time I got to the little burg of Brady, Texas.

Brady must be the place they mean when they talk about deep in the heart of Texas. It’s on Highway 87, right in the center of the state, southwest of Fort Worth and northwest of Austin. Population about 5000, not counting turkeys. They got a million turkeys there, I guess. It’s a sort of poultry shipping point.

But Brady was no worse than a lot of other towns I’d been in since I left St. Louis and Kansas City. And they’ve got a few restaurants there and I was broke„ About a week before Christmas I was wearing a blue-and-white uniform, slinging hash in a local beanery. It wasn’t a bad place, for a change. The boss didn’t make any passes. the kitchen was clean, and they had a nice Formica counter that was easy to wipe off.

I saw Red Stapleton for the first time on Wednesday night, December 22. I’ve had plenty of time to remember the date since then.

That was the day I should have started home to Kentucky.

He came in about 9 o’clock at night and ordered coffee at the counter. I don’t know if you ever met any Texans. If you have, you know they don’t just sit down and say “Coffee, please,” like most folks. They got to make a little speech about it.

So this red-haired fellow said, “Say thar, purty gal, how about a cuppa java for ol’ Red, here?”

I had to smile the way he said it. He looked about my own age, 19. So that was mistake Number One—I smiled when I gave him his coffee.

He flashed me that big, crooked grin that I came to know too well later on. “You’re new here, aren’t you?” he asked.

That was a standard opening. I’d heard it a hundred times before in the past few months. I should have said, “I’m not that new,” and turned my back on him. But I didn’t.

I’ve tried to analyze my feelings many times since then. I’ve figured it out that I was just plain lonely.

In the first place, Red was young the same as me. He was a local fellow, which seemed to put him in a different class from the average guy making a pitch. And there’s no getting around it, there was something attractive about him.

He wasn’t handsome; not by a longshot. He was a long-legged beanpole with a big, sunburned hawk’s nose and lots of freckles. His hair was the color of raw carrots. He talked real ‘Taixas’ drawl. It was a voice I liked to listen to at first. Later, it grated on me like fingernails on a blackboard.

Well, Red kept talking, telling me what a “purty gal” I was, and I kept listening and laughing in spite of myself. He must have drunk five cups of coffee sitting there bulling that night.

He was strictly local, like I said, practically a hayseed, born and raised right there in Brady. He’d had about the same amount of school as me, maybe less. He’d done a little time in the army until they booted him out—he was real proud of that.

“I was too tough for the army,” he’d say, grinning real foxy.

He wasn’t working. He’d had some kind of farm job but didn’t like ft. His idea was to get out of Brady, “get to a big city and do some livin’.”

Oh, he was full of big talk. He knew how to “make connections.” He could “get onto some big deals” if he could just get away from Brady. He had friends who were “picking-up heavy sugar” in Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

All that didn’t impress me too much. I figured he was just blowing smoke, like most kids do when they’re 19 or 20 years-old. But one thing did strike me: He had a cousin in Covina, a little town just outside Los Angeles. He was talking about driving out there to see this cousin.

That started the wheels turning in my head, all right. I still had California on the brain. This sounded like a free ride to Hollywood.

I saw quite a bit of Red Stapleton in the next couple of days. He’d hang around the restaurant, drinking coffee and shooting the breeze. After work, I’d go to the drive-in theater with him. He had a beat up 1950 two-door Ford sedan.

We talked about California and how we’d like to put Brady, Texas behind us. I don’t know what was the matter with me. I sort-of went for the guy at this stage. Sure, I’m a woman; I’ve got no heart of stone; I can be sweet-talked.

Let’s just make one thing crystal clear: At this point I wasn’t objecting when Red put his arm around my shoulder, and I wasn’t turning away when he kissed me. But our personal relations never got out of hand, either then or later.

Getting on with the story, I made a serious boo-boo on Christmas Eve. I must have had stars in my eyes—Hollywood stars. Anyway, Red had no money —I mean he was stony—and little ol’ Mary Ruth says she’d pay for the gas if he wanted to head for California.

“You won’t have to pay all the way, Mary,” Red promised. “You just put in a tankful now and we’ll go see a relative of mine in San Antonio. She’ll give me dough.”

We pulled into San Antonio on Christmas Day. One of Red’s woman relatives wasn’t exactly overjoyed to see him. I gathered she was pretty broke. She finally told Red she was sorry, but nothing doing. No money.

Red put on quite an act—at least, that’s what I thought it was at the time. I know better now.

He stormed and threatened. If the woman wouldn’t give him money, he knew other ways to get it. He went out to the car and came back in the house waving an ugly, black automatic. It was one of the 9mm foreign makes.

“This is my meal ticket,” he told the woman. “This’ll take me anywhere and buy me anything I want.”

The relative acted scared to death. I thought Red was just showing off, though I wondered about the gun. He finally stuck it back in his pocket and said we’d drive on to El Paso and visit some of his cousins.

The woman was glad to see us leave. I could tell that.

As soon as we got on the highway, Red took the gun out and put it on top of the heater, under the dashboard.

“Red,” I said.

“Yeah?”

“Where’d you get that gun?”

He glared at me just as he had with his relative. His eyes were hard and narrow. ‘With his big hooked nose, he looked like an eagle ready to pounce. “I got it from a guy. Why?” There was a challenge in his voice.

“No reason,” I said quickly. “I just wondered. Did you mean what you told that woman?”

“About what?”

“About using that gun?”

“Listen, you just forget about that gun. I told you, we’re going to see my relatives in El Paso, and then we’re going to see my cousin in Covina. Isn’t that what you wanted—to get to Los Angeles?”

“Yes, but—”

“But nothing!” He was starting’ to get mad again, like with that woman. “You’re getting a ride! Now shut up!”

I shut up. After a while, he seemed to get over it. I decided he’d just been kidding.

It seemed I was right when we got to El Paso. We saw his uncle and a couple of cousins. They were nice people, and they treated Red and me like special guests.

That night, December 26, one of the cousins suggested we should all go to a movie. Red didn’t want to. “You go along, Mary,” he said. “I think I’ll just cruise around town.”

So I went to the show with Red’s cousin. We saw “The Caine Mutiny.” It was real good.

Red and I left for Los Angeles the next morning. Red paid for the gas when we filled up. That surprised me. I was real naive. “Did your uncle lend you some money?” I asked.

He gave me a wise grin. “I’m loaded,” he said, tossing me his wallet. “Take a look. 0l’ Red knows what he’s doing.”

I counted the money. There was almost $250 in greenbacks. “That’s a lot of money,” I said. That was all I could think of to say. It was the most money I’d ever seen at one time in my life.

“You string along with me and there’ll be plenty more where that came from,” he said. He was awful pleased with himself.

“Your uncle didn’t give you all that,” I said, beginning to see the light.

“Hell no, he didn’t! I knocked over a liquor store last night.”

“You stole it?” I guess I looked like a five-year-old kid that finds out there isn’t any Santa Claus.

“Wise up, baby,” he said. “It happens every day. Why shouldn’t I get my share? I just took the old persuader and stuck it in this guy’s face and he handed over 250 bucks.”

I edged over as far as I could in the seat. “I don’t want any part of it. You let me off at the first town we get to.”

His hand shot out like a snake. His fingers closed around my neck till I couldn’t breathe. I could see the little red hairs on his arm. He kept driving along, holding my throat till things started turning black.

Then he let go. “You started this trip with me and you’re not getting off till the end of the line,” he said. His voice sounded like rocks grinding together. “You got that clear in your mind?”

I couldn’t squeak out a word. I just nodded, glad to be able to draw a breath again.

From then on he watched me like a cat does a mouse. When we’d stop to eat, I couldn’t even go to the ladies room without him waiting outside the door.

We got into Los Angeles late the afternoon of December 28, barely speaking to each other. I was hoping he’d let me out. I offered to swear on a stack of Bibles that I’d never mention the holdup, if he’d only let me go. I told him I knew I could get a waitressing job somewhere.

But Red wasn’t buying that. We’d go see his cousin in Covina, he said, and if I kept my mouth shut there he’d think about leaving me in Los Angeles.

Well, we saw his cousin. Honestly, I think he had a cousin in almost every town in the country. I kept my part of the bargain. I didn’t let on that there was anything wrong. When we left there about midnight, Red had changed his mind.

“I want to see Frisco (San Francisco),” he said. “I’ll think about letting you off when we get there. Los Angeles is too close to El Paso.”

I gave up then. I hadn’t slept for forty-eight hours. While Red drove through Los Angeles, I asked if I could climb in the back seat and take a nap. He checked to make sure the gun was still on top of the heater. Then he said okay.

I curled up on the seat and cried myself to sleep. The last thing I remember before I dropped off was a street sign that said “Hollywood Boulevard.”

Then I was dreaming that I’d heard a shot. I woke up with a start. It was pitch dark and cold, like just before dawn. I was alone in the car. The motor was running and the door on the driver’s side was open.”

The car was parked alongside some gasoline pumps at a Union 76 filling station. Outside I could see a big red neon sign that said “Grapevine Coffee Shop.”

I saw all this in the wink of an eye, the time it takes you to come awake from a dream. Then I heard another shot.

Red came running out of the service station office. He had the gun in his hand and he was stuffing something in his pocket as he ran. I could hear his breath coming in great panting gulps as he threw himself behind the wheel. He slammed the door and jerked the Ford into gear with one motion. The wheels spun on the concrete and we were racing down a broad, divided highway with hills all around us. I could see the lights of a city in the valley far ahead.

Red didn’t say anything for about a mile. I held my breath in the back seat, watching the speedometer needle move past 80.

He knew I was awake, though. He glanced around at me. Finally, he spoke: “You know, I think I killed a man back there.”

My throat felt like cotton. I said, “You must have done something bad. I heard two shots.”

“I just meant to hit him over the head,” he said. “But the old guy (Orville Johnson) talked too much and my gun went off.”

I started crying. He swung his arm around behind him and struck me on the forehead. “Shut up, you little—!”

After a while, he threw a handful of bills into the back seat and told me to count it. It added up to $101.

It was almost daylight when we got to Bakersfield, the town I had seen from the hills. I knew then we were on Highway 99, going north. Red drove on to a town called Avenal and rented a room at a motel.

Of course, I know a lot more about this murder now than I did then. I didn’t find out some of the details till a week later.

Just to fill in the pieces, Red apparently got the idea for a holdup driving over the Ridge Route from Los Angeles while I was sleeping. This filling station is at a place called Grapevine, just where you start down into the San Joaquin Valley.

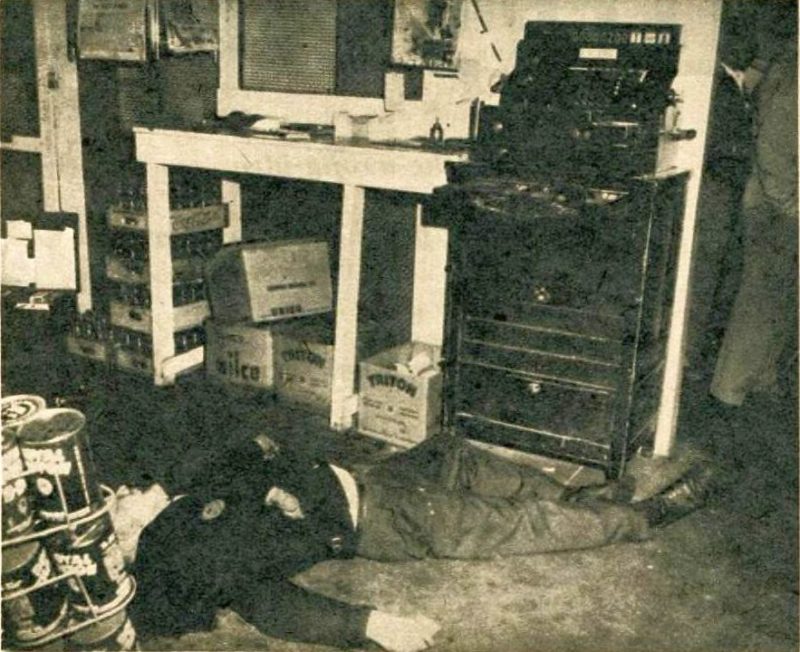

It’s the busiest station on the pass. They have a restaurant there, too, but the place was practically deserted when Red came along. That was about five o’clock in the morning of December 29.

The station attendant was a nearsighted fellow named Orville Johnson, a 59-year-old bachelor. He’d been working there about a year, living in a cabin behind the place.

I still don’t know exactly what happened when Red went in that station. Even Sergeant Joe Taylor doesn’t know all the details. Red is the only one who knows the full story, and naturally he tells it the way that sounds best for him.

Anyway, Red went in there and stuck him up. The old fellow took off his gloves and opened the register. The gloves were still there when Sergeant Taylor arrived a couple of hours later.

Then Red and the old man apparently scuffled. Red’s first shot went under the door; the officers found the bullet mark there later. Red’s second shot hit the old man.

A motorist who was having carburetor trouble found the attendant dead on the floor about 5:30 A.M.

But to get back to my troubles.

You can imagine how it was sitting there in the motel with Red all day. He wasn’t just a kid bandit any more. He was a murderer. I knew it and he knew I knew it. He knew that if I got out of his sight, his goose was cooked. We were like a couple of wild animals caged up together. I sat in a chair across the room from him. He sat on the bed, fingering that automatic and staring, staring, staring at me. I could read his mind like a newspaper headline. “Should I kill her?” he was wondering.

He wanted to, but he didn’t have the guts.

We stayed there till dark, then started driving again. We headed back the way we’d come, but turned east through the Tehachapi toward the Mojave desert. Red had some idea about going to Arizona and getting into Mexico.

I pleaded with him. “Not me, Red, please,” I begged. “You’d have a much better chance to get away alone. Just put me out beside the road. You’ll never hear of me again.”

He gave me a wild-eyed look and reached down for his gun over the heater.

“You aren’t going any place,” he said. “You know too much.”

I was begging like a child. “Please, Red. I’d never tell on you. You know that.”

“Don’t ever try to get out of the car unless I tell you to,” he said. “I can shoot straight. You know that now. I’d shoot you down like a jackrabbit if you tried to get away.”

I don’t know how I lived through those next few days. We just kept driving. Red would avoid the towns. He wouldn’t stop except at little out of the way places where he could watch me all the time.

For food, he’d usually stop at a lonely highway station where they had a lunch counter. Then he’d make me get in the back seat while he got out with his gun and the car keys. He’d hurry inside and order a couple of sandwiches, looking out the window at me all the time. He’d bring them out to the car and we’d eat while we rode.

Later, he got a little more confident. He’d take me into a roadside restaurant and sit with me in the last booth in the rear. He wouldn’t leave me alone for a minute for fear I’d talk to a waitress.

Once, I picked up a newspaper and saw an article about a manhunt for a service station holdup-murderer. Red jerked it out of my hand. He read it all the way through, but he wouldn’t tell me what it said.

Neither one of us could sleep. I tried to stay awake so as not to miss a chance to get away. Red didn’t dare close his eyes for fear I’d get that chance.

New Year’s Eve we were stopped by the Arizona Highway Patrol. It was one of those drunk traps.

The officer came up to the car and poked his head in the window beside Red. “Better take it easy tonight,” he said. “Lot of drunks out on the road.”

I was sitting in the front with Red. I thought I’d risk it. “Officer—” I said.

I felt Red’s body stiffen. He took his right hand off the wheel and shoved it down to his leg.

The patrolman looked at me. “Yes, Miss?” he asked.

I knew where Red’s hand was heading. If I opened my mouth, he’d have that gun out in a flash and there’d be more shooting.

“I was just wondering how far it was to the next town,” I said, stupidly.

The officer looked at me as if I were a little cracked. “You can ‘see it right up ahead,” he said.

The next two days are just a hazy blur to me, I guess. It was like sleepwalking. I dozed part of the time in spite of myself. I remember we went through Tucson and Phoenix.

Red was close to the breaking point. He was bleary-eyed and unshaved. He muttered to himself constantly. I could catch snatches of what he said. He seemed to be explaining to himself why he had killed the man at the service station, trying to justify himself.

We arrived in Nogales, Arizona, on January 2. That was going to be Red’s jumping-off place for Mexico. It’s right on the border.

I might be in Mexico now—or I might be dead—if it hadn’t been for the brakes. Something went haywire and we couldn’t go on without fixing them.

We stopped at a service station on the outskirts of Nogales. The attendant was a fellow named Jose Munoz. Good old Jose—I’ll never forget him as long as I live.

It was hot that afternoon and Red bought beer for himself, the attendant, and me. I guess he figured if he gave me something to put in my mouth, I wouldn’t have time to do any talking.

He wanted me to sit in the car while he worked on the brakes. I argued with him. The attendant gave him a funny look. “Why can’t she get out of the car?” he asked. He asked it like he expected an answer.

Red didn’t know what to say. Finally, he nodded. “Okay, but you stay right here in the station.”

Red climbed under the car. Just his feet were sticking out and he was making a lot of noise with the tools. I decided he couldn’t hear me. I tried to tell Jose Munoz that Red was a killer wanted by the cops.

Munoz listened politely, sort of smiling. He thought the beer and the heat had affected me, I guess. “He killed a man,” I whispered. “I tell you he’s got a gun. Don’t you believe me?”

Red came out from under the car now. I don’t think Jose Munoz ever would have believed me if it hadn’t been for the accident that happened next.

Red wanted Munoz to ride around the block with us while he checked the brakes. We all got in the car, me in the back seat, the two men in front, Red driving. We turned the corner a little fast, and plop, the automatic fell off the heater and landed on Munoz’ feet. Red snatched it up and shoved it back on the heater, mumbling something about using it for hunting. But I could almost hear the wheels turning in Munoz’ head.

Back at the station, Red did some more work on the brakes and bought some more beer. Just before we left, Munoz sidled up to me. “I’ve got his gun in the station,” he said. “Ditch him the first chance you get.” My chance came an hour later. Red and I were eating a sandwich—in a rear booth as usual. He was running low on money and talking about another holdup. That seemed to remind him of the gun. He got up suddenly and hurried out to the car.

He was back in a moment, his mouth twitching, his eyes half scared, half-angry. “Where is it?” he asked, hoarsely.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said, out-loud.

“The gun,” he whispered. “Have you got it?”

I stood up. The restaurant was fairly crowded. I knew he wouldn’t try anything in there. “Excuse me,” I said, brushing past him. “I want to powder my nose.”

I went into the rest room and stayed there. I must have stayed two hours. When I looked out once, he was pacing up and down on the sidewalk in front of the car. When I looked out the second time, the car was gone.

There isn’t much more to tell. When I was sure I was safe, I went to the Nogales police station and told my story to Chief James McDonald. He got the gun from Jose Munoz at the filling station, and put out an all-points bulletin for Red Stapleton’s arrest.

Sergeant Joe Taylor and James Barbour, Mr. Wooldridge’s investigator, flew to Nogales and took me back to Bakersfield. They were a little suspicious about me at first. That’s why I was charged and booked into the county jail. Later, when they checked out my story and found it was all true, they transferred me to the Juvenile Home.

Red Stapleton was arrested at Tucson, Arizona on January 7, when a policeman spotted his car. He surrendered without a fight.

Of course, he tried to lie his way out at first. He wisecracked and bragged and bullied, just like he’d done with me. But it didn’t do him any good. Sergeant Taylor took the gun to the police lab in Los Angeles and had it tested. The tests showed that Red’s gun was the murder gun.

Red gave up then. He admitted everything. Well, he’s going to be put away now and I’ll never have to see him again after next week, when I testify before Judge Howden. It doesn’t make any difference to me whether he gets first- or second-degree.

I just don’t want to have anything more to do with any red-headed, fast-talking blowhards from Brady, Texas All I want is to get back where I belong in good old Middlesboro, Kaintuck.

Epilogue

Mary Rombalski did not return to Kentucky. On February 4 (1955), Max Stapleton pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to life in prison by a Kern County judge. Mary Ruth testified against him at his sentencing hearing. Afterward, the charges against her were dropped and she was released from Juvenile Hall to a local Baptist minister who helped provide her with a place to live and employment. In March, she moved to Los Angeles—and Hollywood. Nothing else is known about her life after her story appeared in the May 1955 issue of Front Page Detective magazine.

—###—