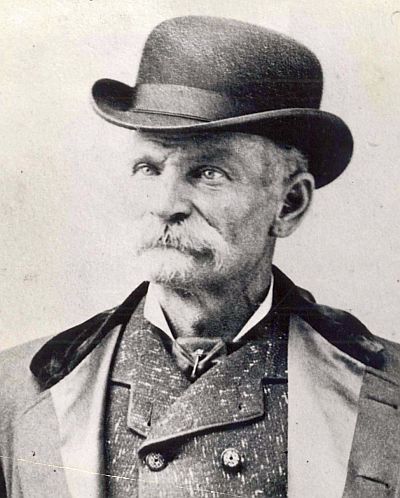

The True Story of ‘Black Bart,’ aka Charles Boles

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part II: Pacific Coast Cases

On August 12, 1877, the stage running from Fort Ross to Russian River was held up by a lone highwayman wearing a mask and exhibiting a shotgun. There were no passengers on the stage and after obtaining $325.00 from Wells-Fargo’s treasure box, the bandit very courteously bid the driver good-day and disappeared.

On July 28, 1878, the stage running between Quincy and Oroville was held up by a robber whose general appearance and conduct indicated that he was the same individual who committed the Russian River robbery. On this occasion he obtained jewels and money valued at $600.00 from Wells-Fargo’s treasure box.

After the stage departed, he picked up a Wells-Fargo waybill and dedicated the following verse to the company, which was afterward found at the scene of the holdup:

“Here I lay me down to sleep,

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat

And everlasting sorrow.

Yet come what will—I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse,

And if there’s money in that box

‘Tis money in my purse.

BLACK BART, P. 0. 8.”

As the mail was also robbed on this last occasion, the Federal government joined Wells, Fargo & Company in offering large rewards, but this did not stop “Black Bart,” for he held up two other stages within a few months afterward. The first was the stage running from Covelo to Ukiah and the second was on the road from Weaverville to Shasta.

On November 3, 1883, the twenty-eighth and last stage was held up by this lone and courteous bandit. On this date he stopped the stage running from Milton to Sonora, near Copperopolis. The driver, J. McConnell, was the only occupant, and the highwayman ordered him to unhitch the horses and hand out Wells-Fargo’s box, from which the robber took $4,100.00 in amalgam and $550.00 in gold coin.

At this stage of the proceedings, an Italian boy with a rifle carelessly thrown over his shoulder, came down the road. This seemed to alarm the robber, who grabbed his loot and ran. McConnell procured the rifle from the boy and fired several shots at the fleeing highwayman, who, in his haste, dropped a handkerchief on which was a laundry mark, “F. 0. X. 7.” This was the only clew as to his identity.

Captain Harry Morse took charge of the case. Working on the theory that the robber probably visited the country regions only for the purpose of committing these crimes and then probably enjoyed his ill-gotten gains in the metropolis, a search was made in the laundries in this city to ascertain who received laundry with this mark.

After a search of the entire city it was finally ascertained that T. C. Ware, a laundry agent on Bush Street near Montgomery, used this mark to designate a customer known as “Charles E. Bolton.”

Morse then ascertained that Mr. Bolton resided in room 40 at the Webb House, located at 27 Second Street, and that he posed as a mining man whose “interests” required him to make frequent trips to the mining regions. A “shadow” was placed on this building and Captain Morse made frequent visits to the laundry office.

One day while there, Mr. Bolton was seen approaching, and Ware agreed to introduce Morse to him, representing that he (Morse) was a mining man. When Bolton arrived, the introduction took place and Morse stated that he had some ore which he wished to have examined, and as Ware had stated that Bolton was a mining man, the latter agreed to accompany Morse for the purpose of making the examination, but when they reached Wells-Fargo’s office, Morse took him into Detective Thacker’s private room.

Bolton was about fifty years of age, immaculate in appearance and an extremely interesting conversationalist. When he learned the nature of the investigation he pretended to be indignant and threatened those who were detaining him.

A search was made of his room and a Bible was found in which was written : “To my beloved husband, Charles E. Boles.” Handkerchiefs similar to the one dropped were also found.

Boles was then taken to San Andreas, and after a severe examination he made a complete confession of the twenty-eight robberies he had committed.

He stated that his right name was Boles, and that he served in an Illinois regiment during the Civil War. He proudly boasted that he had resolved never to harm a human being, and that the shotgun which he invariably carried was as harmless as a broomstick, as it was never loaded. He then took the officers to the spot in the hills where he had buried the proceeds from the last robbery.

He pleaded guilty to the last robbery and on November 21, 1883, was sent to San Quentin for seven years.

During his visits to San Francisco between robberies, he ate at a restaurant patronized by a number of local detectives and frequently joked with them regarding the inability of the country officers to capture “Black Bart.”

In 1888 he was released and stated before leaving prison that he would commit no more crimes.

When asked if he would write any more poetry he replied : “Did you not hear me say I would commit no more crimes?”

Immediately after leaving San Quentin Boles came to San Francisco and, after calling on the officers who were instrumental in his conviction, he disappeared, never to be seen or heard of again.

See “Final Days” at Wikipedia.org

—###—