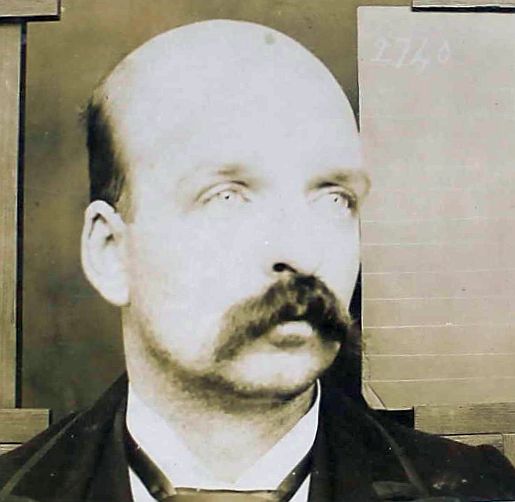

The Murder of Samuel Jacobson by Sydney Bell, 1890

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part I: San Francisco Cases

About 1 o’clock Sunday morning, August 17, 1890, Samuel Jacobson, of the trunk dealers’ firm of Steele & Jacobson, located at No. 222 Bush Street, staggered into his home at No. 2300 California Street, where he resided with his parents and sisters, and stated that he had just been shot in the abdomen.

He said that as he alighted from a westbound California-Street car at Webster Street, a few steps from his home, two men approached him, and that the smaller of the pair, who wore a mask, pressed a pistol against his body and commanded him to throw up his hands. He stated that he grappled with this man, who shot him, and then both of the robbers fled down Webster Street.

A Chinatown guide named John Shaw said that he was in the immediate vicinity when the shot was fired, but that he saw no one on the street.

In addition to this statement, the conductor on the westbound car, which passed at the time, stated that the only passenger to leave his car at Webster Street was a Chinaman.

This caused many to suspect that Jacobson was equivocating, and it was rumored that a big scandal would be unearthed if the true facts were known. It was even hinted that the reason that Shaw saw no one on the street was because the shooting occurred in Jacobson’s own home. On August 18 he died, and when the autopsy was performed a 32-calibre bullet was found near his heart.

At the time of the shooting Jacobson was keeping company with a milliner named Miss Courtney, and it was said that they would have been married had it not been that they disagreed regarding religion. This circumstance caused another rumor to be circulated that Jacobson had been murdered by some rival for the young lady’s hand.

At this time, two footpads were operating in this city, and as they usually wore masks, the only description given was that one was tall and that the other was short.

A few weeks after the death of Jacobson, a tall young man named Edward Campbell, who was employed as a solicitor for the Singer Sewing Machine Company, became particularly friendly toward Detectives Hogan and Silvey, who were detailed to apprehend the two footpads. He was “too sweet to be wholesome” and it was suspected that he aimed to creep into favor with the detectives because he feared that he would need their friendship at some future date.

Upon investigation, it was found that under the name of Harry Weston he was arrested by Sheriff Cunningham, of Stockton, Cal., for horse stealing in 1885 and was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, but was pardoned in 1888.

To prove that he could be of service, Campbell informed these officers that a thief named Charles Schmidt had shipped a number of stolen articles from San Jose to San Francisco. A watch was set and when Schmidt called for the property he was detained and it was found that some of the articles had been stolen from citizens in San Francisco, by the “tall man and the short man.”

Schmidt, who was very tall, then confessed that he had been implicated with a short man named Sydney Bell in seven robberies.

Shortly after Schmidt’s capture, Campbell put a very significant hypothetical question to Detective Hogan. He asked : “If A. and B. started out to commit a robbery, but after starting B. refused to participate in any crime and insisted on going home, and then, without warning of his intentions, A. suddenly whips out a revolver and holds up a citizen who offered resistance and is killed by A., would B. be guilty of any offense ?”

Hogan gave an evasive answer, but it was then understood why Campbell sought the friendship of the police.

After this conversation, Campbell was kept under constant surveillance, as it was expected that he would be seen talking to the short man who murdered Jacobson, Campbell being almost as tall as Schmidt.

As they did not meet, Captain Lees finally told Campbell that he was positive that he (Campbell) knew the facts regarding the Jacobson murder. .

As evidence had already been obtained showing that he was the other tall man who operated with the short man, he, Campbell, stated that he was willing to confess if granted immunity. This being satisfactorily arranged, Campbell made the following confession:

In May, 1890, I was sent out with Sydney Bell to canvass for the Singer sewing machine.

We became confidential and Bell suggested that I assist him in robbing belated pedestrians. After some hesitancy I consented and we executed several ‘jobs’ successfully.

On the night of August 17, I met Bell at my home, 235 Clara Street, and we traveled out through the Western Addition. Bell showed me a 32-calibre revolver and a policeman’s club loaded with lead.

Throughout the entire evening I protested against robbing any one and Bell became provoked at me. We arrived at Webster and California Streets after midnight and I told him that I intended to take the next eastbound California-Street car and go home.

Before it arrived a westbound car passed and a man whom I have since learned was Samuel Jacobson, alighted, and, without consulting me, Bell went up to him and commanded him to throw up his hands.

Jacobson grabbed Bell, who fired a shot, and then Bell and I ran along Webster Street and started for town. When we separated Bell said that he would get someone that night.

He came to my house the next night and stated that he had robbed a fellow of $240 after we parted that morning.

In addition to the crime just related, Campbell admitted that he assisted Bell in a great number of robberies, but that Bell frequently operated alone.

It was then ascertained that Bell resided on Stockton Street, near Bush, but as he had an appointment to call on Campbell, whose home was on Prospect place, it was decided to allow Campbell to go to his home, closely followed by detectives.

Campbell was anxious that the arrest should not occur in his house, so it was arranged that he and Bell should leave the house together and the arrest was made on the street.

When taken into custody Bell had the loaded club and 32-calibre pistol described by Campbell, in his possession. He would not admit that he had participated in the Jacobson murder, but he confessed to sixty-five robberies.

Three of his victims, Edward Crome, J. H. Curley, the tailor, and Peter Robertson, the well-known newspaper man, positively identified Bell and he chatted with them in regard to the details of the crimes.

He told Robertson that he was one of the most belligerent persons he had ever dealt with, and when Curley informed him that he (Curley) wore a magnificent diamond ring on the night he was robbed, Bell stated that if he had known that at the time, he would have bitten Curley’s finger off.

Schmidt was Bell’s companion during these three robberies.

When a visit was made to Bell’s room, a little sixteen-year-old girl was found there who posed as his wife, but who afterward admitted that she ran away from her home in the East, where her parents had surrounded her with every comfort, and that her meeting with Bell in San Francisco was purely accidental. She was sent home, and as her parents were prominent people her name was never made public.

On January 19, 1891, Bell’s preliminary examination for the murder of Jacobson began before Judge Rix. He was held to answer on that charge and was subsequently held to answer for the three robberies already referred to.

On April 22 the trial for murder began in the Superior Court and on May 7 he was found guilty of murder in the first degree.

This case was appealed to the Supreme Court and a new trial was granted, but as the evidence in the robbery cases was so strong that Bell saw that it would be useless to fight the charges, it was decided to abandon the murder case and proceed with three robbery charges. He pleaded guilty to each charge on September 15.

On September 17 he was sentenced to serve forty years for robbing Edward Crone, ten years for robbing Peter Robertson and ten years for robbing J. H. Curley.

Schmidt was found guilty of the robberies in which he assisted Sydney Bell, and was sentenced to serve a term in San Quentin Prison. He stated that he would never have committed a crime had he not been swindled out of all of his earthly possessions, and he added that notwithstanding the fact that he had been convicted and sentenced, he had a presentiment that he would never go to a State Prison.

He fully realized his disgrace, and on the day that he was being taken to San Quentin, it was evident that he was laboring under an intense but suppressed excitement.

As he reached the prison gate he placed his hand to his mouth and then turned deathly pale and staggered and fell dead in the arms of the deputy sheriff. An autopsy showed that he died from cynide of potassium poisoning.

Campbell was given his freedom in recognition of the service he had rendered to the prosecution, but he never amounted to anything afterward, being frequently arrested for vagrancy. Bell was paroled in May, 1909.