Serial Killer H.H. Holmes, born Herman Mudgett

The Criminal of the Century, Herman Mudgett, Alias H.H. Holmes

by Thomas A. Duke

published in 1910

—–#—–

Procuring a hammer and chisel he tore down the lower part of the chimney and found almost a full set of child’s teeth, several pieces of human bone and a large charred mass which proved to be a portion of a child’s stomach, liver and spleen, baked hard.

—–#—–

Herman W. Mudgett was born in Gilmantown, N. H., on May 16, 1860, but spent his boyhood days on a farm near Burlington, Vt.

He was extremely bright, ambitious and studious, and at the age of sixteen years he became a school teacher.

On July 4, 1878, at the age of eighteen, he married Clara A. Lovering at Alton, N. H., and about this time he gave up his position as a school teacher to enable him to take a course in a medical school at Burlington, Vt.

A year later, he finished his course at this school and then went to Ann Arbor College, Michigan, to complete his education.

In 1881, Mudgett gained possession of a body that bore a remarkable resemblance to a fellow student who was his closest friend and who had taken out a life insurance policy for $1,000 a short time previously, in which Mudgett was named as beneficiary.

This put an idea into the heads of the two students. They surreptitiously placed this body in the bed of Mudgett’s friend, who immediately disappeared.

There was evidently little or no investigation made regarding the case, as Mudgett collected the insurance without trouble, and presumably divided it with his “dead” chum.

Shortly after this Mudgett left college, and under the name of Holmes procured a position at an insane asylum in Norristown, Pa.

After six months he left this position and proceeded to Philadelphia, where he procured employment as a drug clerk.

He next went to Chicago, where he opened a drug store of his own. Continuing to use the name of Holmes he married Miss Myrta Belknap, in Chicago, on January 28, 1887, thus committing bigamy.

On January 17, 1894, under the name of Howard, he again married in Denver, Miss Georgie Yoke, of St. Louis, being the victim.

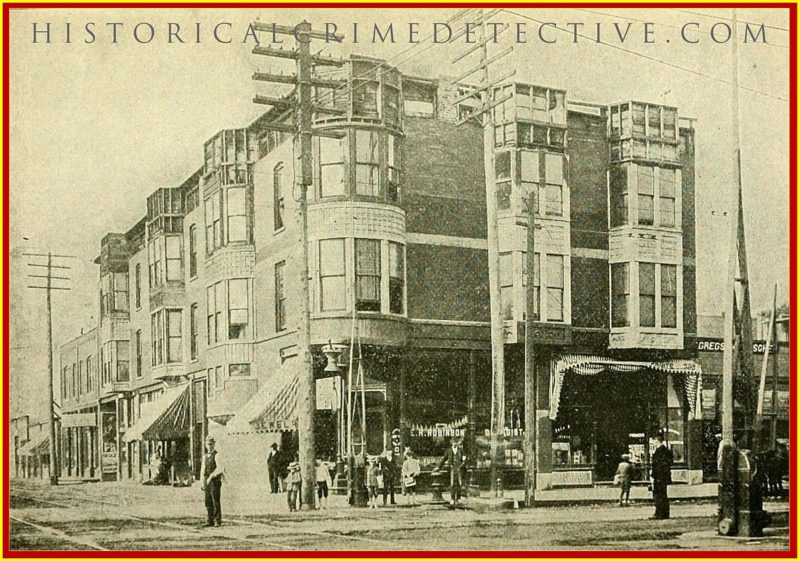

Before marrying Miss Yoke, Holmes traveled about the country under numerous assumed names, engaging in various enterprises, none of which would bear investigation. He accumulated considerable money and constructed a four-story building at the corner of Sixty-third and Wallace Streets in Chicago, which was known as “Holmes Castle.”

About 1889 Holmes met Benjamin F. Pitezel in Chicago, who was afterward suspected of being Holmes’ partner in many crimes.

At that time Pitezel’s family, consisting of a wife and four small children, named Dessie, Alice, Nellie and Howard, lived in St. Louis.

Holmes was a man of medium height and build. He was immaculate in appearance, suave in manners and as this narrative will show, fiendish in disposition.

Pitezel was a mesmeric subject, and Holmes, being possessed of hypnotic powers, discovered this fact, and thereafter Pitezel was so much clay in his hands.

On November 9, 1893, Pitezel took out a $10,000 life insurance policy from the Fidelity Mutual Life Association of Philadelphia, which was made payable to his wife.

Holmes, knowing this, suggested to Pitezel and his wife that Pitezel go to Philadelphia, and under the assumeed name of B. F. Perry, open up an office and put up a sign “Patents Bought and Sold.”

Holmes stated that he would then institute a search among hospitals or medical colleges and find a body having features and physique similar to Pitezel. The body would be surreptitiously placed in the establishment and laid in such a position as to so clearly indicate that death had resulted from an accidental explosion that no questions would be asked. Pitezel would disappear and Mrs. Pitezel’s fourteen-year-old daughter, Alice, would journey to Philadelphia and identify the remains as those of her father. The insurance money would be paid without question, and then Pitezel would quietly return to his family. Mrs. Pitezel offered strenuous objections to the plan, but Holmes commanded Pitezel to do his bidding, and the result was that on August 17, 1894, Pitezel opened his office at 1316 Callowhill Street and put out his sign as directed.

On June 15, 1894, while Holmes, then known as Howard, was in St. Louis arranging details for his latest scheme, he purchased a drug store, upon which he gave a mortgage. Shortly afterward he sold this mortgaged property, and on July 19 he was arrested on a charge of obtaining money by false pretenses in connection with this sale.

While in jail he met Marion Hedgspeth, who, with three others, robbed a train near St. Louis in 1891, and was captured in San Francisco. (See history of Marion Hedgspeth.) Holmes asked Hedgspeth if he knew of any slick lawyer.

The train robber recommended him to J. D. Howe, of St. Louis, and Holmes then foolishly unfolded his whole scheme in regard to Pitezel, to Hedgspeth, and told him that he would give him $500 for his services if the plan worked.

On July 31 Holmes was released on bail furnished by his third “wife.” A few days after being released he proceeded to Philadelphia, where he met Pitezel, alias Perry, and on August 17, the day on which the latter opened his office in Callowhill Street, Holmes accompanied him to a secondhand furniture store located at 1037 Buttonwood Street, and assisted him in selecting furniture.

On August 22 a carpenter named Eugene Smith, who was of an inventive turn of mind, passed this office, and being attracted by the sign, stepped in to discuss the merits of a set-saw he had invented and desired to put on the market. “Perry” listened attentively to his description of the invention and asked him to bring a model the next day. Smith complied with the request, and after an examination of it, Perry predicted heavy sales.

On Monday, September 3, Smith called to ascertain how his device was selling. “Perry” was not in the office, but his hat and coat were there, and Smith, believing he had stepped out for a few moments, waited until he became impatient and left. He returned the next day and again saw no one, but observed that the coat and hat were in the same position. He then made inquiry in the neighborhood and learned that “Perry” had not been seen since Saturday.

His suspicions being aroused he decided to investigate. As “Perry” occupied both floors of the small two-story building, Smith proceeded upstairs, and in a back room he found the mutilated body of Perry. The breast and side of the face were badly burned ; fragments of a large bottle were found near the corpse, and a tobacco pipe and burned match were also found.

The body was removed to the morgue, and after lying there until September 13 without being claimed, it was buried in the potter’s field.

On September 19 Attorney Howe called on Mrs. Pitezel in St. Louis and informed her that her husband was dead, and requested that the fourteen-year-old daughter Alice accompany him to Philadelphia for the purpose of identifying the remains. Mrs. Pitezel then signed a paper prepared by Howe, which gave him power of attorney to collect the money, and he left with Alice, Mrs. Pitezel believing that the child would be instructed to identify the body of a stranger and that her husband was alive and well.

On September 21 Howe, Alice, Holmes and Smith, who discovered the body, called at the Philadelphia office of the insurance company, and after Smith was interrogated the party proceeded with the insurance officials to disinter the remains. Holmes explained that he was a close friend of the Pitezel family and knew that Pitezel was located at 1316 Callowhill Street, under the assumed name of Perry, because of financial troubles in Fort Worth.

When the body was exposed, Alice Pitezel and Holmes immediately identified the remains as those of Pitezel. While the cause of Pitezel’s death was not perfectly clear to the insurance officials, they concluded that the large bottle which was found broken by his side contained some inflammable substance which exploded as the victim was evidently in the act of lighting his pipe.

Against this theory it was argued that the body reclined in a peaceful attitude and the stomach when opened gave forth a distinct odor of chloroform.

At any rate, the insurance money was paid to Howe, who proceeded to St. Louis and paid Mrs. Pitezel the $10,000, less $2,800 deducted for expenses.

As Alice did not accompany Howe, Mrs. Pitezel anxiously inquired as to her whereabouts, but the attorney assured her that Holmes would see that she was well provided for. A few days after this Holmes visited Mrs. Pitezel, who begged piteously to be taken forthwith to her husband and child.

Holmes told her that she must be patient, as the insurance officials were suspicious of the entire transaction and that he considered it advisable for the family to remain separated for the present; in fact, he stated that he had come to get the two smaller children, Nellie and Howard, and take them to Covington, Ky., where a nice old lady was caring for Alice.

Mrs. Pitezel made strenuous objections to this plan, but after some argument Holmes persuaded her to consent to their going.

The monster then produced a note on which he stated that he and Mr. Pitezel had obtained $16,000 from Attorney Samuels in Fort Worth, and in order to save their property there a portion of the amount must be forwarded immediately.

In this manner he obtained $7,000 from her, and after instructing her to proceed to the home of her parents in Galva, Ill., he departed on September 28 with the two children, after promising that the entire family would be reunited at the earliest possible moment.

At this time Alice was in the keeping of a lady in Covington, Ky., and at Holmes’ request she wrote a cheerful letter to her mother in which she spoke of the kind treatment accorded her. This greatly increased Mrs. Pitezel’s confidence Holmes, and she ceased to regret parting with the other children.

Immediately after the letter was forwarded, Holmes had Alice meet him and the other two children in Indianapolis, and from thence they journeyed to Cincinnati.

He left Cincinnati on October 1 with the three children and proceeded to Indianapolis, where he put the children in the Circle Hotel and then met Miss Yoke and stopped with her at another hotel in the neighborhood. This lady believed herself to be Holmes’ lawful wife and knew nothing of his misdeeds.

He represented that he was endeavoring to place a patent copier on the market with which he expected to make a fortune, and that his mysterious journeys were in connection with this business. He planned so that Miss Yoke never met the children.

The next day Holmes took Alice and Nellie to Detroit, but little Howard had mysteriously disappeared. Holmes wrote for Mrs. Pitezel to bring the baby and Dessie to Detroit, where they were to meet Mr. Pitezel. Holmes and his “wife” stopped at one hotel, the two girls at another, and when Mrs. Pitezel arrived she stopped at Geis’s hotel, a very short distance from the New Western, where Alice and Nellie were staying, under the name of Canning, that being the name of their grandparents.

Holmes instructed the children to remain in their room, and when he met Mrs. Pitezel he stated that an investigation had been instituted and he deemed it necessary to delay the reunion of the family. As to the investigation, Holmes unconsciously spoke the truth.

It will be recalled that he promised to pay Marion Hedgspeth $500 if the insurance swindle was consummated, but as time rolled by and Marion saw nothing of the money, he decided to turn informer for two reasons: First, to get revenge, and second, to gain the good will of those who might be able to assist him. So on October 9 he wrote a letter to Chief of Police Harrigan, of St. Louis, wherein he exposed the entire scheme, but of course he did not believe that Pitezel was dead.

On October 18 Holmes took his “wife” and Nellie and Alice Pitezel to Toronto, Canada, he and his wife stopping at he Walker House under the name of Howell, and the children were registered at the Albion under the name of Canning, as in Detroit.

Mrs. Pitezel was instructed by Holmes to leave on October 19 for Toronto, with Dessie and the baby, and if he deemed it safe she could there join the remainder of the family. By this time the poor woman was almost insane from grief, as she began to fear the worst. She asked Holmes to allow her husband to write to her, but he stated that the authorities might intercept the letters.

Holmes called on Mrs. Pitezel in Toronto and told her it was impossible to reunite the family at that time, and he sent her with Dessie and the baby, Wharton, to Ogdensburg, N. Y., and thence to Burlington, Vt., where Holmes rented a house at 26 Winooski Avenue, where he intended to murder the remainder of the family, but fortunately the opportunity did not present itself. (After the family left this house a large bottle of chloroform was found in the cellar, where it had been left by Holmes.)

The mother now began to lose hope of ever seeing her husband and three children again, and she finally returned to her relatives in Galva, Ill.

Pleading urgent business. Holmes left Miss Yoke about November 1 and went to Gilmantown, where he remained with his legal wife until November 17, when he went to Boston. The detectives got on his trail while he was at his old home and traced him to Boston, where he was arrested on November 19. His effects were searched, and several letters were found which had been written by the Pitezel children to their mother.

Holmes believed that the authorities either suspected him of having substituted a body, falsely claiming it was Pitezel’s, or wanted him for horse stealing in Texas.

Having in mind the manner in which horse thieves were frequently punished in Texas he immediately stated that he had defrauded the insurance company by swearing the body found in Callowhill Street was Pitezel’s, when, as a matter of fact, he stated, Pitezel had left America with his three children.

He expressed a willingness to return to Philadelphia and plead guilty to the insurance swindle charge, providing he was not turned over to the Texas authorities. As he made a statement in which he claimed Mrs. Pitezel was a party to the fraud, she was arrested and brought to Boston with Dessie and the baby. Mrs. Pitezel was subjected to a severe cross-examination, but at its conclusion the authorities were convinced that she was innocent. However, on November 19 Mrs. , Pitezel and Holmes were taken to Philadelphia as prisoners, the two children and Miss Yoke accompanying the party. It was June 3, 1895, before Holmes was brought to trial for defrauding the insurance company. He willingly pleaded guilty.

At this time several months had elapsed since either Pite-zel or his three children had been heard from, and the authorities were becoming convinced that Holmes was guilty of far worse crimes than defrauding an insurance company by substituting a body. They strongly suspected that he was guilty of at least four murders.

As Pitezel was suspected of having an intimate knowledge of Holmes’ criminal career, it can be seen that his desire to permanently seal Pitezel’s lips was only equaled by his desire to obtain the bulk of his life insurance. Mrs. Pitezel would eventually realize this, and if her husband was not returned to her she would inform the authorities, with the result that the body in the potter’s field would be subjected to a closer examination, which would mean that Holmes would probably be charged with the murder of Pitezel.

The older children were probably informed by their mother of the insurance swindle and were assured that their father would return, and of course children talk. The officers assumed that Holmes realized all this and that he decided that his safety was assured only after the entire family was disposed of. He could not hope to kill six people at once without being detected, so he decided to separate them and murder them one by one.

On December 27, 1894, Holmes made another statement substantially as follows:

“I regret that I have made false statements in the past, but the following are the facts :

“While Pitezel was at 1316 Callowhill Street he drank very heavily, and I took him to task about it. He appeared to be despondent and said that he had better drink enough to kill himself and have done with it all. The next morning I visited his place, and using a key I entered the building. I found a letter addressed to me, which I destroyed, in which he said I would find his body upstairs. I went upstairs and found him lying dead on the floor. There was a rubber tube in his mouth which was attached to a quill run through a cork in a large bottle containing chloroform.

“I had arranged with Pitezel that the body substituted for his should be burned about the face and hands by pouring a mixture of benzine, chloroform and ammonia on it and then setting it on fire ; that a large bottle was then to be broken and a smoking pipe and burned match placed nearby ; the object being to show that the person supposed to be Pitezel or Perry, had actually ignited the mixture in the bottle while lighting the pipe, and that the bottle exploded and death was caused by the burns. Seeing Pitezel’s body, I decided to carry out this plan in all its details. The three children are now in Europe in the custody of Miss Minnie Williams, formerly of Fort Worth, Texas.”

It was easily proved that Holmes told the truth regarding the identity of the dead man found in Callowhill Street, but the remainder of the statement was not believed.

It was now clear that Holmes was not guilty of substituting a body, and action regarding that case was postponed, pending a further search for the missing children.

The District Attorney then looked about for a detective possessed of sufficient ability and determination to undertake this gigantic task, and he decided upon Frank Geyer, of the Philadelphia Police Department.

As eight months had elapsed since the children were last seen, and as it was probable that persons who had seen them had forgotten their faces, it can be readily understood that the obstacles confronting this officer were apparently insurmountable.

On June 26, 1895, he started out with photographs of Holmes and the three children.

He proceeded to Cincinnati and began visiting the hotels. When he reached the Hotel Bristol at Sixth and Vine Streets, the clerk identified the pictures as those of a man and three children who registered under the name of Cook.

It was the detective’s theory that Holmes had murdered the children in some house in the suburbs of some city, so he began to make rounds of the real estate offices, both in the city and in the suburbs. When he arrived at the office of J. C. Thomas, at 15 East Third Street, the clerk recognized the picture of Holmes and Howard Pitezel, and it was learned that Holmes had rented a house at 305 Poplar Street, where he only remained two days. Geyer proceeded there and interviewed a Miss Hill who resided next door.

She saw Holmes moving an immense stove into the house, but no furniture.

The singular incident so impressed her that she unconsciously watched the proceeding very closely. Holmes observed this and decided to change his plans, but before leaving the house with Howard he offered the stove to the “inquisitive” lady.

Geyer then proceeded to Indianapolis and visited the hotels and real estate offices. He gathered valuable information as to the route taken by the children from the letters which they wrote to their mother, but which Holmes withheld and foolishly kept in his possession.

Here Mr. Herman Ackelow was located, and he at once identified the pictures of the children as those of guests who stopped with him when he conducted the Circle House. He also stated that the children were held in their room practically as prisoners, and although they were constantly crying, they refused to state the cause of their grief. In a letter written by Alice to her mother just after they left Indianapolis, and which was found in Holmes’ pocket when arrested, the girl innocently remarked that “Howard” (meaning her brother) “is not with us now.”

This convinced Geyer that the child had been murdered in or near Indianapolis, but he failed to obtain any clew at that time upon which to work.

The detective then proceeded to “Holmes Castle” in Chicago, but he learned nothing there regarding the Pitezel children. He then proceeded to Detroit and found that on October 12 Nellie and Alice Pitezel were registered at the New Western Hotel, but neither Howard nor the trunk were seen there.

Thinking that Holmes might have had Howard and the trunk with him, Geyer proceeded to learn where Holmes stopped, and found that he and Miss Yoke were registered as “G. Howell and wife” at the Hotel Normandie, but as neither the boy nor the trunk were seen at this place the detective became more convinced than ever as to where little Howard met his fate. But intent on tracing the girls first, Geyer proceeded to Toronto, Canada, where Mrs. Pitezel next met Holmes.

He arrived on Monday, July 8, and found that Holmes and Miss Yoke registered on October 18, 1894, at the Walker House, under the name of Howell and wife, and that the children were registered at the Albion Hotel under the name of Canning. Herbert Jones, the thief clerk of this hotel, stated that on October 25 Holmes called for the children, paid their bill and they were never seen again.

As it was known that Holmes went to his first wife in Gilmantown a few days after this, Geyer became convinced that the fiend had rented a house in Toronto for the purpose of murdering the two girls.

He prepared a list of all real estate agents and had the newspapers publish the pictures of the children and print his theories.

He then began a canvas of the real estate offices, which lasted for days, but nothing was accomplished. Finally Geyer learned that a Mrs. Frank Nudel had rented a house at No. 16 Vincent Street, in October, 1894, to a man who only remained there a few days and acted quite mysteriously. He immediately proceeded to the house, but when he reached the house located at No. 18 Vincent Street he showed the pictures of Holmes and Alice to Mr. Thomas Ryves, who resided there, and that gentleman instantly recognized them as the photographs of a man and girl who were at the house next door for a day and then disappeared.

Mr. Ryves furthermore stated that this man borrowed a spade from him, saying he wanted to plant some potatoes.

On receiving this information Geyer hurried to the home of Mrs. Nudel, and when he showed the lady and her daughter Holmes’ picture and asked them if they had ever seen the man, they instantly replied that it was the picture of the man who rented their Vincent Street property. Geyer’s enthusiasm now knew no bounds. He rushed back to No. 18 Vincent Street and borrowing the same shovel Holmes had used, proceeded to the next house, No. 16, where a family named Armbrust was then living.

After hurriedly making known his mission the lady told him to proceed with his investigation.

He examined the house, and on raising the linoleum in the kitchen he discovered a trap door which led to a dark cellar.

He procured a light, and after examining the ground he found a spot which appeared to have been recently disturbed. He had only been digging a minute or two when a terrible odor arose which became more horrible with each shovelful of dirt removed. He finally unearthed what was apparently the arm of a child, but as the flesh fell from the bones he decided that great caution would be necessary or the bodies would fall to pieces. So Undertaker Humphreys was called in and the digging proceeded, with the result that the terribly decomposed bodies of Nellie and Alice Pitezel were found.

While the features of the children could not be recognized,, the clothing and hair were readily identified by the heartbroken mother, who started for Toronto as soon as she was advised of the discovery. To make “assurance doubly sure,” Geyer located a family named McDonald, who moved into the house after Ho-imes left, and they found a wooden egg, from which, when parted in the middle, a little “snake” would spring out. Mrs. Pitezel recognized this as a toy she had purchased for her little girls.

These bodies were entirely nude when found, and the clothing spoken of above was taken from the dead children by Holmes and stuffed up in the chimney in the parlor with some straw and set on fire, but as they did not burn, the chimney was left in a clogged condition, and Mrs. Armbrust on examining it found the clothes and fortunately did not dispose of them.

It is perhaps needless to say that Holmes’ object in removing and destroying the clothes was to prevent the bodies from being identified.

On July 19, after the burial of the Pitezel children in Toronto, Geyer proceeded to Detroit, where he learned that Holmes had rented a house at 241 East Forest Avenue, and an investigation showed that he had dug a grave in the cellar, but before he had an opportunity to complete his work information reached him that detectives were on his trail, and he abandoned his plans for the time being.

Geyer left Detroit on July 23 and returned to Indianapolis to search for little Howard Pitezel’s body.

For days and days he made a tireless round of the real estate offices both in the city and for miles out into the suburbs.

On August 1 he went to Chicago, as a child’s skeleton had been found at “Holmes Castle,” but Geyer became convinced that this was the remains of some other unfortunate child, and in a few days he returned to Indianapolis. The search now included all the small towns within a radius of several miles from the city. After nearly a month’s work no place remained unsearched but the pretty little town of Irvington, about six miles from Indianapolis. In this town Mr. Geyer, who was now almost exhausted, wearily made his way to the real estate office of an elderly man named Brown. After relating his story and showing his pictures hundreds of times, after weeks of fruitless labor and nights, of restless sleep, Geyer again related his story and showed his pictures of Holmes.

The old man adjusted his glasses and finally remarked that it was the picture of a man who rented a house from him in October, 1894.

As the house belonged to a Dr. Thompson, who had seen the tenant, Geyer, who had now taken a new lease of life, hurried to him, and the doctor not only identified the picture as a likeness of his tenant, but told the detective that a boy in his employ named Elvet Moorman had seen this man with a boy at the house.

When interviewed Elvet immediately identified the pictures of Holmes and little Howard.

He stated that his duty compelled him to go and milk a cow every afternoon, which was kept in a lot in the rear of the house Holmes rented, and that while so engaged Holmes asked him to help him put up a stove when he had finished milking.

The boy complied with the request, and while assisting Holmes he asked him why he did not use a gas stove instead of a coal stove, and Holmes replied that “gas was not healthy for children.” Little Howard was present when this remark was made.

Geyer then proceeded to the vacant cottage, which was across the street from a Methodist church. He searched the house from cellar to roof and discovered nothing. He then looked through the lattice work between the piazza floor and the ground and saw some pieces of an old trunk.

He broke in after this and found that in one place on the remains of the trunk a piece of blue calico had been pasted, and on this calico was the figure of a flower. As the earth appeared to have been disturbed Geyer began digging with a vengeance, but all in vain.

He then proceeded to the barn, and there found an immense coal stove. As it was growing late Geyer quit for the night, with the intention of resuming the search in the morning. Mrs. Pitezel was then with her folks in Galva, Ill., and Geyer telegraphed this query : “Did missing trunk have blue calico with white flower over seam on bottom ?” and the answer was, “Yes.”

When Geyer left the cottage, two boys named Walter Jenny and Oscar Kettenbach, who knew of Geyer’s mission, decided to “play detective.” They began looking for evidence in the cottage and ran their busy hands into a stovepipe hole in the chimney in the basement. They brought out a handful of ashes, but in those ashes were several teeth and small pieces of bone. While Geyer was still in the telegraph office at Irvington he was informed of this discovery, and rushed back to the cottage.

Procuring a hammer and chisel he tore down the lower part of the chimney and found almost a full set of child’s teeth, several pieces of human bone and a large charred mass which proved to be a portion of a child’s stomach, liver and spleen, baked hard.

The corner grocer then came forward and announced that the boy, whose picture Geyer showed him, came to his store in October and left his coat there, saying that he would call for it, but never returned.

Mrs. Pitezel was again sent for and she identified the coat as one belonging to little Howard.

Geyer then located Albert Schiffling, who conducted a shop at 48 Virginia Avenue, Indianapolis, and he stated that on October 3 Holmes, accompanied by little Howard, called on him and left some surgical instruments to be sharpened. But the child little realized that they were being sharpened for the purpose of dismembering his body so that it could be cremated in the stove afterward set up.

A coroner’s jury, after hearing the evidence, had no hesitancy in rendering a verdict to the effect that Howard Pitezel was murdered by Holmes.

On September 1, 1895, Detective Geyer returned to Philadelphia, and after being congratulated on all sides for unraveling one of the greatest mysteries in criminal history in America, he proceeded to bring the archfiend to justice.

Holmes having been indicted for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel, the trial was set for October 28. While Detective Geyer was engaged in locating missing members of the Pitezel family, the authorities in Chicago, Fort Worth, Texas, and numerous other cities were investigating Holmes’ career previous to the death of Pitezel.

When the officials inspected “Holmes Castle” at Sixty-third and Wallace Streets in Chicago, they were astounded at the elaborate preparations made by this criminal to trap his victims and dispose of their remains right in the heart of a great city.

This structure was a four-story brick building covering a lot about 50×120 feet. The lower floor was occupied by stores, a drug store being on the corner; the outside rooms of the three upper stories having square bay windows and were arranged into apartments and offices, with the exception of that part used by Holmes in connection with his human slaughter-house. His rooms were on the second floor, and in his office was a vault from which neither air nor sound could escape when the door was closed.

From his bathroom, which had no windows and no means of lighting, unless an artificial light was brought in, was a secret stairway leading to the basement, and in order to reach this stairway the rug in the bathroom was raised, and there was found a trap door. The laboratory on the third floor was connected with the cellar in a similar manner. There was no other means of reaching this particular part of the cellar except by these secret stairs.

In this cellar was a large grate with a removable iron covering in front, and under this grate was a large firebox. In an ashpile in the corner several small pieces of burned human bone were found, and in the center of the room was a long dissecting table, upon which was found blood and indentures from surgical instruments.

On July 24, 1895, Detectives Fitzpatrick and Norton, of the Chicago police, began a systematic search for evidence of crime committed by Holmes in this building. They dug up the cellar, and buried in quicklime they found seventeen ribs, three sections of vertebrae of the spinal column and several teeth attached to the upper portion of a jaw bone. A part of a child’s cape coat, which was decayed and lime-eaten, and a woman’s garment thoroughly saturated with blood and brown with age were also found. These discoveries were all taken to Dr. C. P. Stingfield, and after a microscopical examination he declared that the stains on the woman’s garment were human blood and that the bones were portions of the anatomy of children from eight to fourteen years of age. In one of his numerous statements Holmes claimed that the Pitezel children had gone to Europe in care of a Miss Minnie Williams. This resulted in an investigation as to the identity of Miss Williams, and also resulted in two more murders being charged to Holmes:

Miss Williams entered Holmes’ employ as a stenographer in 1893. At this time he was at the head of the so-called “Campbell Yates Manufacturing Company,” with “offices” in the castle.

Learning that she and her sister, Nettie, owned a valuable piece of land in Fort Worth, Texas, he professed love to Miss Minnie, and it is said that they lived as man and wife in the castle. In the later part of 1893 Minnie, at Holmes’ request, wrote to Nettie that she was about to be married, and requested Nettie, who was a teacher in an academy at Fort Worth, to proceed to Chicago at once to attend the wedding.

Nettie arrived in Chicago shortly afterward, but within a short time both girls mysteriously disappeared and were never seen again.

In February, 1894, Pitezel, under the name of Lyman, proceeded to Fort Worth from Chicago and placed a deed on record from one Bond to Lyman for a valuable piece of ground at Second and Rusk Streets.

The “Bond” was supposed to have obtained the title from Minnie Williams. On this property “Lyman” began erecting a building, and shortly afterward, Holmes, alias “Pratt,” appeared on the scene.

Their business affairs became badly muddled and they left town before the building was completed, but not before Holmes stole a horse and engaged in numerous other shady transactions.

On July 19, 1895, the police made another search of the Castle and found more charred bones, several metal buttons and part of a watch chain. C. E. Davis, who formerly conducted a jewelry store in the Castle, identified the watch chain as belonging to Minnie Williams, and also stated that he repaired it on two occasions. He furthermore stated that he had seen Minnie Williams wearing a dress on which were buttons similar to those found.

On August 4 Detective Fitzpatrick found Minnie Williams’ trunk in Janitor Pat Quinlan’s room in the Castle, a clumsy effort having been made to paint over her initials on the trunk.

When confronted with this evidence Holmes denied having killed the Williams girls, but he related a weird tale about Minnie attacking and killing her sister Nettie, and to protect Minnie, whom he claimed to love, he advised her to go to Europe, and he carried Nettie’s body to the lake and sank it.

In 1880 I. L. Connor, a jeweler, married a beautiful eighteen-year-old girl named Smythe, in Davenport, Iowa. About one year afterward a little daughter was born. This child was named Gertrude. In 1889 Connor moved with his family to Chicago and he obtained employment in Holmes’ drug store, which was located in the Castle.

Mrs. Connor was still a beautiful woman, and being possessed of considerable business ability, Holmes consulted with her about several of his schemes, and they became quite confidential. Differences arose between Connor and his wife, with the result that he left, but Mrs. Connor and Gertrude remained at Holmes Castle.

In 1892 both Mrs. Connor and Gertrude disappeared. While in prison in Philadelphia, Holmes was interrogated as to their fate, and he stated that Mrs. Connor died from an operation, but that he did not know what became of Gertrude.

On August 2, 1895, some of Mrs. Connor’s wearing apparel was found in the castle and identified by her husband. On this same day Janitor Pat Quinlan and his wife confessed that they saw the dead body of Mrs. Connor in the Castle. On July 22, 1895, A. Minier, a nephew of Mrs. Connor, swore to a warrant charging Holmes with her murder.

Her father, A. Smythe, produced a letter supposed to have been written by her in November, 1892, wherein she stated that she contemplated going to St. Louis. Smythe stated that the writing was a poor imitation of his daughter’s penmanship.

In 1892 Holmes was president of the A. B. C. Copying Company, which also had offices in the Castle, and Miss Emily Cigrand was employed by him as a stenographer. She was formerly employed in a similar capacity at the hospital at Dwight, Ill., where Pitezel, under the name of Phelps, was being treated for a time. She was dismissed from this position and Pitezel recommended her to Holmes.

She and Holmes became very intimate, and were known as Mr. and Mrs. Gordon where they had apartments near the corner of Ashland Avenue and West Madison Street. Miss Cigrand made a practice of writing several times a week to her parents, who resided in Oxford, Ind., but after December 6, 1892, they never heard from her again.

Holmes was suspected of having murdered several other persons with whom he had business dealings and who suddenly disappeared, but as the evidence against him in these cases is by no means conclusive, no details are given.

On July 28 Charles M. Chappell, of 100 Twenty-Ninth Street, Chicago, reported to Lieutenant Thomas, of the Cottage Grove Station, that he worked for Holmes as a “handy man” during the summer of 1892. On October 1 Holmes asked him if he could mount a skeleton. Chappell said he thought he could, and Holmes gave him the skeleton of a man to mount, and when the work was completed Holmes paid him $36.

In January, 1893, Chappell was given another skeleton of a man to mount. When Holmes first showed him the body it was in the laboratory and there was considerable flesh on it. As Holmes had a set of surgical instruments and a tank filled with fluid for removing the flesh and apparently made no attempt to conceal anything from him, Chappell thought he was doing the work for some medical college.

In June, 1893, Holmes gave Chappell another skeleton to mount, but as he never called for it Chappell turned it over to the police on the day he made these disclosures.

On October 28, 1895, the trial of Holmes for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel began in Philadelphia. The work of selecting jurors had hardly begun when Holmes had a misunderstanding with his attorneys and they temporarily withdrew from the case. Holmes personally conducted the examination during their absence.

It was the theory of the prosecution that Holmes chloroformed Pitezel while the latter was either asleep or intoxicated. Three physicians testified that the death was caused by chloroform poisoning.

Mrs. Pitezel, who had become a physical wreck, identified a photograph as the picture of her deceased husband, and also identified the clothing removed from the body in the potter’s field as having belonged to Mr. Pitezel. She then testified at length regarding the insurance swindle conspiracy, and repeated the many conversations she had with Holmes regarding the whereabouts of her husband. To show that Pitezel was not contemplating suicide, as claimed by Holmes, Mrs. Pitezel produced a letter written by her husband some days previous to his demise, in which he expressed his intention to have his family join him in Philadelphia at an early date.

Several persons who knew Pitezel as “Perry” when he kept the place at 1316 Callowhill Street, identified the picture of Pitezel as the photograph of Perry. Many of them saw the corpse and stated that the remains were those of the man they knew as Perry. Several of these witnesses also testified that “Perry” was last seen alive at 10:30 p. m. on Saturday, September 1, 1894, when he visited a neighboring saloon to purchase a supply of whisky to last him over Sunday, the Excise law preventing the sale of liquor on Sunday.

Eugene Smith, who placed the patent set-saw with Perry, testified to finding the body on the following Tuesday, and experts testified that the condition of the body indicated that the man was dead at least two days. This would mean that he died on Sunday.

Miss Yoke, who had believed she was Holmes’ (or Howard’s) legal wife, testified that she and Holmes were at this time living at 1905 North Eleventh Street. That on Saturday evening a man called to see Mr. Holmes and that Holmes informed her that he was a prominent railroad man who was about to leave a large order for his patent copier, but that Holmes afterward admitted the man was Pitezel. She also stated that Holmes left their apartments at 10:30 a. m. Sunday, and did not return until 4:30 p. m., at which time his excited and overheated condition attracted her attention.

They hurriedly packed their belongings and left that night for Indianapolis, remaining there but a few days and then proceeding to St. Louis, where Holmes called on Mrs. Pitezel. It was proved that on August 9, 1894, Holmes telegraphed $157.50 to the Chicago office of the Fidelity Mutual Life Association, to pay the half-yearly premium on Pitezel’s policy. No witnesses were called for the defense.

In charging the jury, Judge Arnold, in commenting on Holmes’ absolute power over Pitezel, said:

“Truth is stranger than fiction, and if Mrs. Pitezel’s story is true it is the most wonderful exhibition of the power of mind over mind I have ever seen, and stranger than any novel I ever read.”

On November 2, 1895, the case was submitted to the jury, and after deliberating a short time a verdict of guilty was returned.

On May 7, 1896, Holmes was hanged in Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia. He assumed an air of utter indifference to the end. Some days before his death, when it was evident that all hope had vanished, Holmes made a “confession,” wherein he admitted that he had killed twenty-seven persons, but on the scaffold he contradicted this statement and claimed that the only persons for whose death he was either directly or indirectly responsible, were two women upon whom he performed criminal operations.

—###—