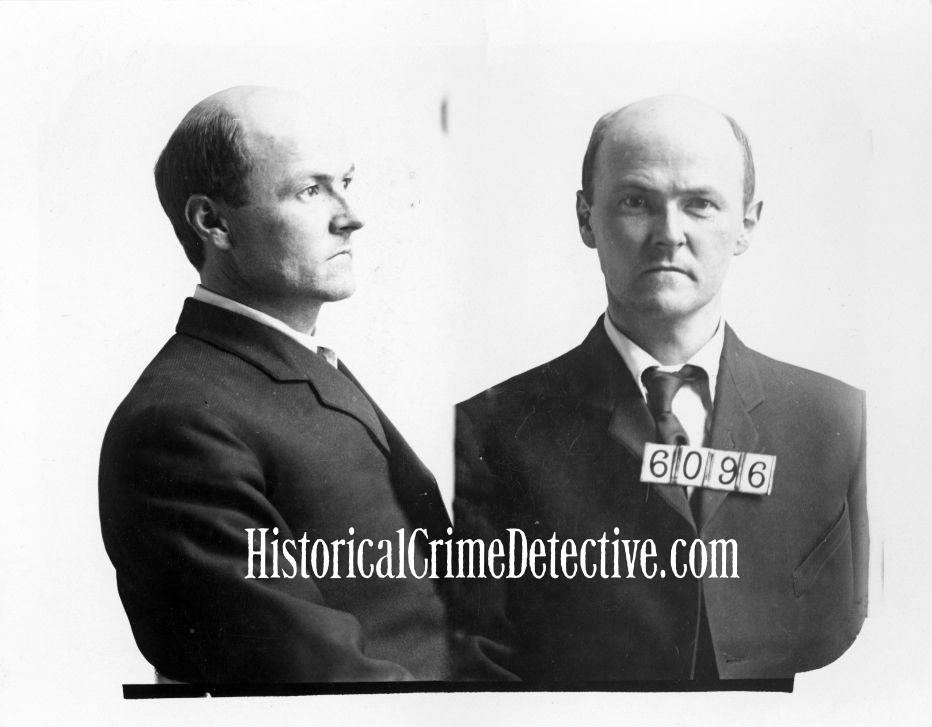

Mug Shot Monday! Azel D. Galbraith, 1904

Home | Mug Shot Monday, Short Feature Story | Mug Shot Monday! Azel D. Galbraith, 1904Between the years of 1898 and 1904, Azel D. Galbraith was working his way up the ladder in Colorado’s mining industry as a bookkeeper and manager. He was held in high esteem and his name occasionally appeared in Colorado newspapers. Although he was married with a young son, his success went to his head and he began to think he was entitled to more. As the business manager of a mine in Russell Gulch in Gilpin County, he traveled often to Denver and on one occasion in 1902, he met Mrs. Lottie Russell, a single woman despite her prefix (honorific). The two began a wild love affair and to enhance his sexual pleasure, or to ease his guilt, Galbraith also began drinking heavily for the first time in his life.

Predictably, the affair turned into an expensive one as Galbraith spent his life savings to keep his lover happy with new dresses, jewelry, dining out in Denver’s best restaurants, tickets to the best shows in town, as well as expensive trips back east.

When his savings ran out, Galbraith began embezzling money from his company. In early March 1904, he was fired by his employer, AJ Richards, who owned the Topeka Mine in Russell Gulch, a now abandoned mining town with an ironic name. Before or immediately after he was fired, Galbraith stole a large number of blank company checks.

[Note: The house in which he murdered his wife and son is still standing and is said to be haunted by a local team of “paranormal investigators.”]

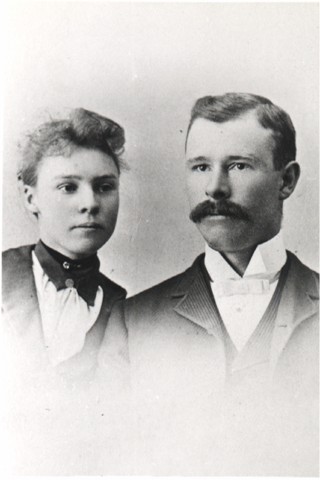

Jennie (Lamb) Galbraith seen here with her half-brother, James Casper Morger. Photo Courtesy of Sharon Morger Jones, great-grand niece of Jennie.

Rather than tell his wife, Galbraith pretended he was still employed at the mine for several days until he could figure out his next move. On the morning of March 9, he and his wife were lying in bed together discussing their future. With no knowledge her husband had been fired, Mrs. Jennie Galbraith chatted freely about various personal objectives she had for their son and the family. Around nine o’clock, Galbraith distracted his wife and when she turned away from him, he shot her in the head with a .32 caliber pistol.

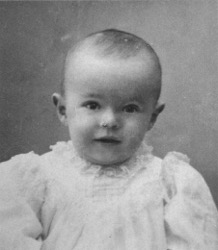

Donald Galbraith as an infant. Photo courtesy of Sharon Morger Jones, great-grand niece of Jennie (Lamb) Galbraith.

Galbraith placed his wife back in the bed and covered her up as if she were sleeping. He then went outside and called for his eight-year-old son. Donald, who was playing nearby with some other children, obeyed his father and ran home. Galbraith then persuaded him to lie down between him and his mother on the bed so they could talk. While pointing at the window, Galbraith remarked “Look at that little bird.” When Donald turned to look, Galbraith shot him in the head.

Galbraith arranged the bodies of his dead wife and son by folding their arms across their chests and crossing their legs at the ankles. He then pulled the quilt over their heads and left for Denver.

For the next month, Galbraith stayed in Denver, visiting his lover as often as he could. He also began drinking heavily and whenever he was low on funds, he would cash one of the company checks. During his time there, he burned through $1,000, the 2016 equivalent of $24,000.

On April 8, he was apprehended by two Denver detectives who had a warrant for his arrest for theft from his former employer. The next day, authorities in Russell Gulch searched his home and found the bodies of his wife and son exactly where he had left them thirty-one days earlier.

Galbraith was interrogated and at first, denied any involvement. Eventually, he faltered and confessed, claiming he killed them because he had lost his job, and wanted to save them from a life of poverty. He said he was going to kill himself too, but lost the nerve, and hadn’t completed his task, yet.

After they grilled him some more, Galbraith told them the real reason he killed his family: he wanted to be with Lottie Russell.

Galbraith was taken to the county seat, Central City, and held in the local jail for trial. When he arrived, twenty armed deputies had to surround the building to prevent a lynch mob from killing him. Although he pled guilty, Galbraith was given a jury trial which began on June 15, and ended thirty-six hours later. After forty minutes of deliberation, the jury found him guilty of first degree murder and recommended the death penalty. On July 7, the judge pronounced sentence with a death date set for October 16, to be carried in the Colorado State Prison in Canon City.

However, two days before he was to be executed, he was granted a thirty day reprieve. Over the next six months, he received three more reprieves as the state considered its capital punishment laws. It had been eight years since the state had carried out an execution, and the laws needed to be dusted off and re-examined. After various legal considerations by the state supreme court, his final date was set for March 6, 1905, at 8:00 p.m.

In his final hours, Galbraith ate a light dinner, and then dressed himself in a new black suit, with white shirt and black tie. After the death warrant was read, he was asked if he would like a drink of whisky.

“No more of that for me,” he answered. “That is what put me where I am.”

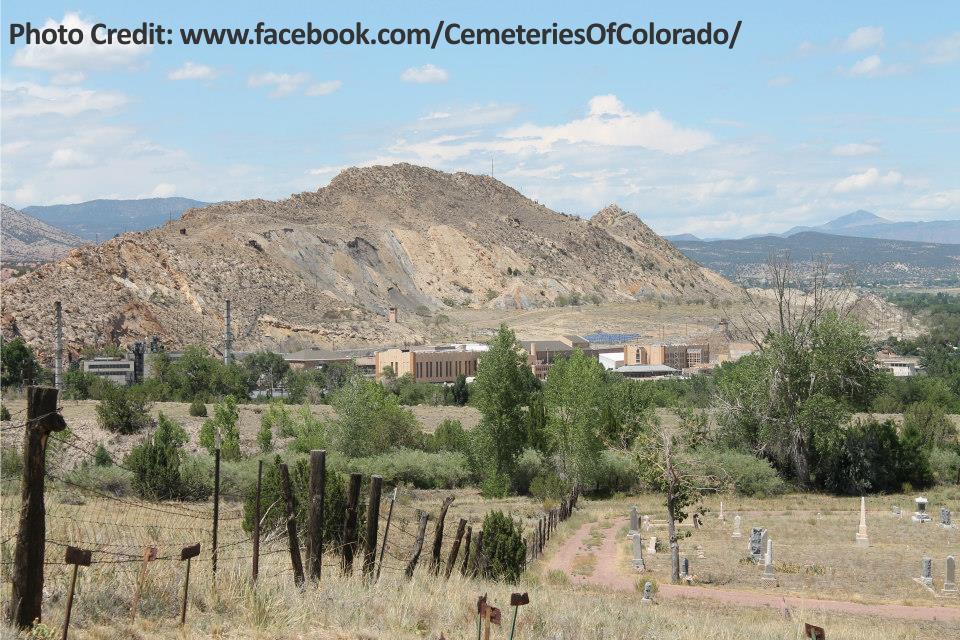

Standing before Colorado’s hanging platform[1], with his ankles, knees and wrists bound, he stood quietly as a Presbyterian minister prayed for his soul. When the word, “Amen,” came, he responded with a simple “Good-bye,” and then the black hood was placed over his head. He was lifted on to the weight sensitive platform and ninety seconds later (see explanation below), he was jerked five feet into the air, and then fell back three feet, breaking his neck. His body twitched two times, and was then motionless as his body swayed back and forth, eventually coming to a stop. He remained there for ten minutes before they cut him down, placed him in a coffin and buried him on nearby Woodpecker Hill, which is the name for the prisoner section of Greenwood Pioneer Cemetery, a public cemetery for Canon City residents.

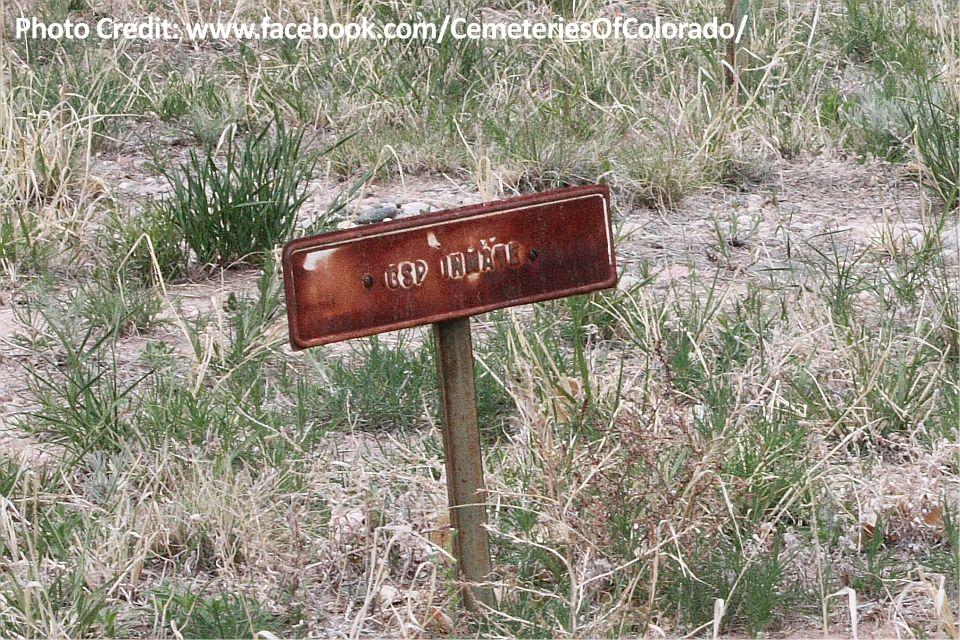

According to the proprietor of the Facebook page, Cemeteries of Colorado, the prisoner section is separate from the area for civilian graves. All prisoners executed by the state, whose bodies went unclaimed by family members, are buried in the prisoner section. As you can see from these photos shared by Cemeteries of Colorado, their graves are marked by an aluminum plate on a steel post. These are nothing more than license plates made in the prison factory. Most of the plates are covered in rust. Beneath that rust, most of them read only: “CSP Inmate.” A small number of them contain the prisoner’s name. Here is a story about the cemetery in the Denver Post website. In one of their photos, you can see the name Louis Monge. I’ll be posting about him later on.

Woodpecker Hill Photo Gallery, courtesy of Cemeteries of Colorado.

P.S. If someone ever gets the chance, please search the April 1904 editions of the Rocky Mountain News or Denver Post to see if there is a sketch or image of Lottie Russell. I would really like to include her image with this story.

[1] It operated by counterweight (water filling a tank) that sent the body upward, dislocating the vertebrae, followed by a sharp drop which snapped the neck. It was dubbed “the automatic suicide machine.”

True Crime Book: Famous Crimes the World Forgot Vol II, 384 pages, Kindle just $3.99, More Amazing True Crime Stories You Never Knew About! = GOLD MEDAL WINNER, True Crime Category, 2018 Independent Publisher Awards.

---

Check Out These Popular Stories on Historical Crime Detective

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, July 18th, 2016 under Mug Shot Monday, Short Feature Story.

Tags: 1900-1919, Colorado, Filicide, Love Triangle, Wife Killer