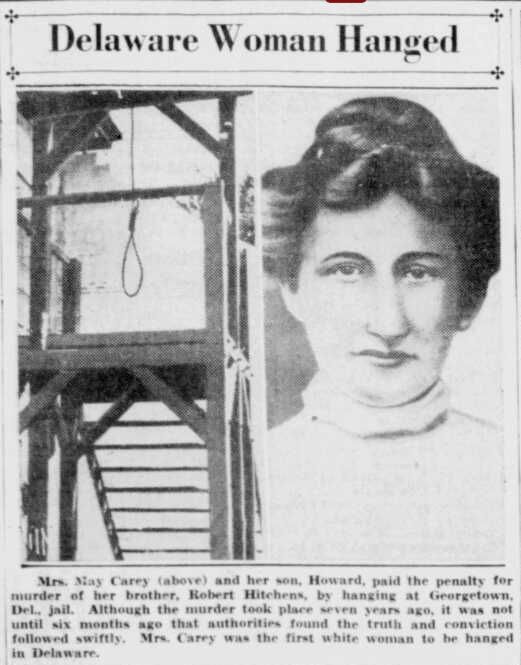

The 1935 Delaware Execution of a Mother & Son

Home | Short Feature Story | The 1935 Delaware Execution of a Mother & SonStory by Jason Lucky Morrow

Posted: December 9, 2015

On November 9, 1927, twenty-year-old Howard Hitchens of Georgetown, Delaware, was growing concerned for his uncle, Robert, whom he had not seen in several days. When he went to the man’s home in nearby Frankford, he found him “beaten to death in a blood splattered room,” the Associated Press reported.

When police arrived, they found the fifty-five-year-old farmer and auto-mechanic crouched in a corner “as if he died in a last effort to ward off blows which fractured his skull in three places and inflicted sixteen other wounds.”

Robert, who was unmarried and described as “sober and industrious,” was known throughout southern Delaware as “well-to-do.” Police theorized that he arrived home to find robbers in his house who then overpowered and bludgeoned him to death. The coroner said he had probably been dead for two or three days which made it more difficult to talk to witnesses who might have seen anything.

After his death, a $2,000 life insurance policy was paid out to his sister, May Hitchens Carey, a widowed mother to three boys, including Howard. After she paid for Robert’s funeral expenses and settled his estate, she was left with $900 ($12,300 in 2015 when adjusted for inflation).

The crime went unsolved for seven years until police got a break in the case on December 5, 1934, when May’s youngest son, Lawrence, was caught burglarizing a house. When questioned about his uncle’s murder, the twenty-one-year-old told police that he heard his mother and two older brothers, Howard and James, planning his uncle’s death. His mother promised Howard “a new car” if he helped her kill his uncle.

On the day of the murder, November 7, his mother sent him to a general store, where his uncle liked to hang-out, to see if he was still there. Lawrence, who was just fourteen-years-old at the time, found his uncle there and reported back to his mother. She then took Howard and James with her to Robert’s house where they waited inside for him to come home.

After Lawrence gave his confession, Delaware investigators quietly arrested and questioned James, who confirmed the story. He told police that when his uncle came home, his brother Howard knocked him half-senseless with a club made of white-oak. His mother then attacked her own brother with a sledge-hammer and together, the three beat Robert Hitchens to death.[1] When they were finished, May poured whiskey into her brother’s mouth, spilled some on his clothes, and then shattered some drinking glasses on the floor.

James, who was just sixteen-years-old at the time, then told police that three of them returned to their home in Georgetown where they burned their clothes and buried the club and sledgehammer.

On Friday, December 7, 1934, fifty-six-year-old May Carey and her son, Howard, were arrested and charged with first-degree murder. Both mother and son denied the charges.

However, during their one day trial held on April 8, 1935, May took responsibility for the crime and said “I drove the children to do it.” Howard agreed and in a last minute plea to the jury, he blamed his mother for “coercing him” to kill his uncle. After three hours of deliberation, the jury found May and Howard guilty of first degree murder with a sentencing recommendation of mercy. For his part, James was convicted of second-degree murder.

In Delaware, as in other states, a first-degree murder conviction typically meant a death sentence. Juries could make recommendations, but the decision was usually left to the presiding judge. Because she was a woman in an era when women seldom received death sentences, newspapers confidently predicted May would be sentenced to life in prison. Since she was the architect of the crime, and took responsibility, many believed Howard would also receive a sentence of life in prison. And in the 1930s, life in prison did not mean life in prison. Instead, May could expect to be paroled in less than ten years, while Howard would likely have to serve ten to twenty before he was released.

When sentencing was handed down on April 26, the judge refused a defense motion for a new trial. He then went on to describe the crime as “the most vicious in the criminal annals of the state, and that the law makes no exceptions to sex.” He then sentenced both mother and son to death by hanging in the Sussex County jail near Georgetown on June 7.

May Carey, who expected the judge to follow the jury’s recommendation of mercy, “screamed hysterically” as the court imposed the penalty.

Due to a quirk in Delaware law at the time, the particulars of the Careys’ case, or both, June 7 was a solid date for the mother and son execution. There would be no appeals.

They each spent their last night alive in adjacent cells with their own spiritual advisors with whom they prayed and sang hymns—the guards occasionally joining in. They ate cake and ice cream together around 2:00 a.m., then slept a little before resuming their prayers and discussions of forgiveness and the afterlife.

At 5:02 that morning, May Carey was led away from her cell and when she passed by her son she turned to him crying and said, “Good-bye Howard. Good-bye boy.”

At 5:02 that morning, May Carey was led away from her cell and when she passed by her son she turned to him crying and said, “Good-bye Howard. Good-bye boy.”

“Good-bye mother,” he replied.

From the cell block she was taken outside to the main courtyard where the state-owned gallows were assembled. It was surrounded by a high-board fence and canvas roof that had been hastily built to conceal the execution according to Delaware law—the spectacle of public executions having long since passed.

“Tight-lipped and dry-eyed,” she walked unassisted up the thirteen steps to the stop of the scaffold. Just before the black hood was placed over her head, she said half-defiantly and with a wavering voice: “My way is clear. I have nothing else to say.”

At 5:07 the trap-door gave way and the bound and hooded figure of a fifty-five-year-old gray-haired grandmother dropped quickly and jerked hard when the thick rope reached its limit. She was allowed to hang there for seventeen minutes before she was declared dead. Seventeen minutes were never more longer when officials stood there watching a bound, hooded dead woman swinging gently back and forth, back and forth.

Howard was taken from his cell at 5:31 and he walked the same one-hundred feet his mother had just taken. Like her, he needed no assistance as he walked steadily up the thirteen steps. At the top, before the black hood was placed over his head, he gave the twelve jurors, who were legally required to be there, Sussex County Sheriff, and the prison physician his last words.

“Gentleman,” he began, “what I did was against my will. I am sure anyone in my place would have done the same. I hope to see my three little ones on the other side.”

He did not mention his wife, Myra, and as the black hood was adjusted, he began mumbling a prayer. He was still reciting that prayer when the trap was sprung at 5:41. He hung there, twitching at first, then swaying, like his mother did, for nineteen long minutes. Finally, at six-o’clock, he was declared dead.

Two hours later, both mother and son were buried together at St. George’s Cemetery, located on a mount near Frankford. More than seventy family and friends attended their funeral.

During the night, while both mother and son slept briefly, Howard’s spiritual advisor spoke with newspaper reporters waiting in an administration building, that “both were very sorrowful and repentant, and in his opinion, well prepared for death.”

Nearly every newspaper account of her death declared that May Carey was the first white woman to ever be executed in Delaware. This was not true, writes author Daniel Allen Hearn in his book, Legal Executions in Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. She was just the first in living memory, and that several white women were executed during the 1700s.

Sources:

- “Farmer was Found Beaten to Death,” Associated Press, The Sedalia Capital, (Missouri), November 11, 1927, page 3.

- “Accuse Mother, Sons of Murder,” Associated Press, The Gettysburg Times, (Ohio), December 8, 1934, page 2.

- “Life Term Facing Mother, Two Sons,” Associated Press, Cumberland Evening-Times, (Maryland), April 10, 1935, page 2.

- “Mother and Son are Condemned for 1927 Slaying,” Associated Press, Titusville Herald, (Pennsylvania), April 27, 1935, page 1.

- “Mother and Her Son Will Die on Gallows,” by Joseph S. Wasney for United Press, Sheboygan Press, (Wisconsin) May 23, 1935, page 10.

- “Woman Pays Penalty for Murder,” Associated Press, The Evening-Tribune, (Marysville, Ohio), June 7, 1935, page 1 and 4.

- “Mother and Son Die on Delaware Gallows for Insurance Murder,” by Leo W. Sheridan for Associated Press, The Kingston Daily Freeman, (New York), June 17, 1935, page 17.

- “Legal Executions in Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia: A Comprehensive Registry, 1866-1962,” by Daniel Allen Hearn, McFarland and Company, Inc., Published 2015, pages 12-13.

[1] Some news reports claim Howard finished him off by shooting him in the head with a pistol, but this claim is inconsistent and went unreported in 1927.

—###—

True Crime Book: Famous Crimes the World Forgot Vol II, 384 pages, Kindle just $3.99, More Amazing True Crime Stories You Never Knew About! = GOLD MEDAL WINNER, True Crime Category, 2018 Independent Publisher Awards.

---

Check Out These Popular Stories on Historical Crime Detective

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, December 9th, 2015 under Short Feature Story.

Tags: 1920s, 1930s, Delaware, Execution, Murder, Women