What Happened to the Bloody Benders?

Editor’s Note: The Bloody Benders were a family of serial killers who lived and operated in Labette County, Kansas, between 1871 and 1873. Nearly a dozen travelers who stopped at their small inn were murdered, and their bodies later found buried on the Benders’ property. The family of four disappeared before they could be arrested. Over the years, a dozen different accounts of their fate were theorized or told. The story below—that they were killed soon after they were suspected in the disappearances of eleven people—is just one of those accounts, but this one comes from one anonymous source, and two deathbed confessions by individuals who all said they were involved in the interrogation and execution of all four Bender family members. It was written and published in obscure true crime magazine in 1951, and has since passed into the public domain.

WHEN Osage Township began seriously to worry, about March 1, 1873, over vanishing travelers on the road from Fort Scott on the Missouri line to Independence deep toward the Indian nations, those travelers had been vanishing for about two years. One more was still to vanish, before Kansas and the world would know how these disappearances had come to pass.

In those days news did not travel fast or far, especially news about lost strangers nobody expected to meet, anyway. People were too busy settling.

First there was only a trail leading southwest into Kansas, bitten through the buffalo grass by heavy-rimmed, ox-drawn wheels. As the Civil War spent itself and a new impulse of settlement strove that way, the trail was hardened and widened by much travel into a highway. Wagonloads of settlers trundled in. Here and there on the treeless plain sprang up farmsteads, relieving a monotony hitherto broken only by occasional meager creeks, small knolls, or willow and cottonwood scrub. Osage Township in Labette County, just east of the new village of Cherryvale, was distin¬guished from the rest of the developing country only by the faint color and flavor of mystery.

Many of the sunburnt farmers had served in the Union Army. Their women were plain and industrious, their children shock-headed, barelegged, shrill. These people built their own houses, butchered and smoked their own meat, ground their own flour from their own grain, sewed their own clothing and cobbled their own shoes. They had no theatres, no libraries. Occasionally there was a barn-raising, a revival meeting, a spelling school. Neighbors made much of every trifle of entertainment and sociability.

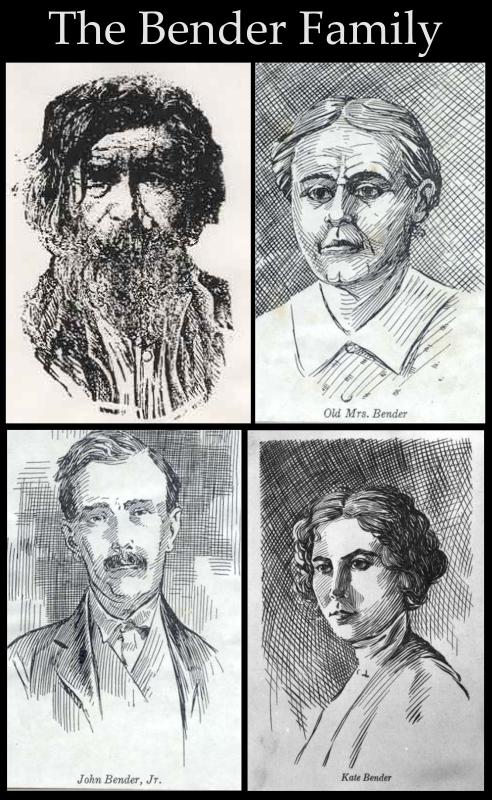

Leroy Dick was Osage Township Trustee. Among his neighbors were Rudolph Brockman, bluff, jovial and Teutonic; Silas Toles, of shrewd Yankee stock; George Frye and Thomas Jeans, modest and laconic farmers; Maurice Sparks, whose quick temper sometimes fulfilled the implication of his name; and the Bender family, whose roadside home did duty as store, restaurant, and hotel.

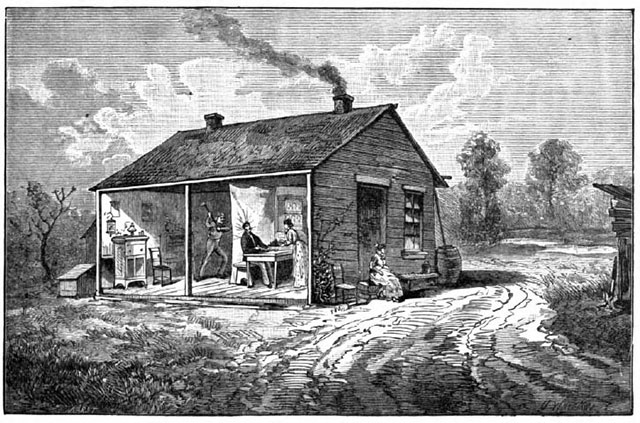

Indeed, the Bender place was almost as much a focus of the country community’s interest as the little Carpenter Schoolhouse, which rendered extra service as church and meeting hall. Not that the Benders lived pretentiously; their house sat a hundred yards back from the road, simple and well kept, an inartistic oblong of unpainted planks. Behind it stood a stable, a pigsty, a railed barnyard and, close to the back stoop, a well curb with rope and bucket. Flanking all these on the right rose an unusual and grateful sight in that new, bald and semi-arid country, an orchard. The Benders came from Germany, where good nurserymen are bred. They had set out fifty young fruit trees in orderly rows, and cultivated them tirelessly. There was promise of apples, cherries and peaches.

The house was divided into two chambers by a canvas cover nailed to a row of perpendicular studding. Against this makeshift partition stood a heavy table, with benches behind and before. Meals were served there. To one side were ranged shelves and a counter, with a small stock of canned goods, bolts of cloth and simple “notions.”

Customers fell easily into talk with the daughter of the house. Kate Bender, acting as storekeeper and waitress, was a bright-haired, rosy girl in her early twenties. An old Kansan still alive in 1930 remembered that her figure was fully and finely curved, and that her red mouth smiled and smiled. He said that she would have been admired in larger and more critical communities than old Osage Township. By all accounts, she was possessed of a sparkling vitality and considerable intelligence. She claimed to be a spiritualistic medium, and had presented séances of delightfully creepy hokus-pokus in the Carpenter Schoolhouse and in Cherryvale, eight miles west. Readily and saucily she joked with any man who glanced her way. Grinning young admirers surrounded her at all the rustic gatherings.

While she gossiped with customers inside the house, their horses were tended outside by her brother John. He was tall and slender, attractive in a somewhat delicate and boyish way. He looked and acted less than his twenty-five years. He laughed even more than Kate did — some neighbors said that John would laugh at nothing at all.

The parents were seen less often. Occasionally, the father left his work in field, stable or orchard to serve a customer or greet a neighbor. William John Bender was nearly sixty, with coarse gray hair and a bulky thickness of body. He stood six feet tall for all the stoop in his powerful shoulders. From under straight brows his dark eyes gazed steadily. He, too, liked to joke, and his German accent made his jokes seem funnier than they actually were.

The mother was the only sober-faced Bender. She looked older than her husband, unhealthily fat, with thin, iron-gray hair combed severely back from a frown-seamed forehead. She spoke almost no English and seemed shy, even dour, to strangers. Usually she stayed in the rear apartment behind the canvas, with the stove and the family’s beds. By Osage Township’s standards, she was a good cook.

These four Benders were to be by far the most widely celebrated dwellers in their community. Their country home, with the canvas partition and the table and the counter, with the barn and the orchard, soon became familiar, by word of mouth and by steel engravings, to a great part of the world.

Why, it began to be asked solemnly as the year 1873 began, did travelers disappear from the road between Fort Scott and Independence?

One man of that region was no admirer of the Benders. John Rader — Happy Jack, they called him — rode into Cherryvale one day, and he did not look or sound happy. To a group of friends in front of a store, he said that riding up to the Bender house in the early evening he had seen Kate through a window, and she was wearing no more clothes than would, in the idiom of the community, dust the keys of a fife. Nor was Kate flustered by Happy Jack’s frankly admiring stare. She had waved for him to come in! And what had he done? Well, he’d done what any real man would do. He had dismounted, tossed his reins to the waiting John, and entered. Disappointingly enough, Kate had hurried on her clothes in the intervening few seconds, and the old folks had come into the front room. They’d made Happy Jack welcome, he’d eaten supper there, and what with one thing and another he’d announced he’d stay the night. They made him a pallet on the floor of the front room.

All this sounded hospitable of the Benders, protested Rader’s friends, and some of them chuckled. But not Happy Jack.

He had gone to sleep. Then he had wakened — someone was stopping a team outside, talking to old William John Bender. Then, of a sudden, the sound of a heavy blow, and a yell like a man’s last sound on earth. Quiet. Moments of quiet. Finally, the Benders, all of them, had stolen into the front room and stood around Happy Jack’s pallet, listening to see if he was awake. Understandably, he had not dared to move. When they left, he lay awake all the rest of the night, and he had ridden away before breakfast.

His rueful face drew a round robin of laughter. His friends comforted him. The Benders do any killing? Shucks, they’d been teasing poor Happy — the Dutch idea of fun.

To support that theory, someone spoke of an old woman’s experience in the Bender home the year before. She had been visiting there, and Kate had grabbed up a knife and screamed that spirits were telling her to kill. The old woman had run for the door, but the Benders did not pursue. They only laughed, the way they must be laughing right now at Happy.

“Well, I don’t like those jokes,” announced Happy Jack Rader. “They can play them on somebody else.”

If the Benders were pranksters, they seemed to be good citizens. During the first week of March, 1873, William John Bender and his son attended a meeting called at the schoolhouse by Township Trustee Dick. Representatives of various families crowded the benches, bearded, roughly-dressed, serious-faced men. Dick, presiding, spoke of several inquiries from the east, about travelers who had dropped out of sight in the Osage Township Country.

“It’s been charged that we’ve got criminals here,” he said.

Maurice Sparks challenged that from a front bench. Nobody had the right to suspect the township folk without proof. A man is innocent, said Sparks, until he is proven guilty. A neighbor snickered, and Sparks grew angrier.

“If anybody doubts me,” he said, “he can come and search my farm. I’m not hiding anything.”

“Neither am I,” said the elder Bender from where he sat with his son. “Search my farm, too.”

Several made the same offer, but Sparks was not through talking. He urged the organization of a company of vigilantes. “Law-abiding men must stand together for protection,” he said.

Again several listeners approved his suggestion, and among these were the two Benders. But the meeting broke up without any definite action being taken. There would be another meeting soon, promised Leroy Dick.

Meanwhile, Dr. William York, a physician who lived in Independence to the southwest, was coming to Osage Township.

Dr. York was a jaunty, confident young man, who had formerly lived in Fort Scott. In February he had visited his old home, where his lawyer brother, A. M. York, was a substantial citizen. Now he was returning to Independence, and on March 9 he paused at an Osage Township farm to ask the sort of question that recently had vexed Leroy Dick and Maurice Sparks. Had anyone seen or heard of his neighbor G. W. Longcohr? Longcohr, with his little daughter, had gone to visit in Iowa some months previously, and people were wondering why he never wrote.

No. Nobody could give any information about Longcohr, sorry. Say, it was getting on for noon, wouldn’t Dr. York alight and take potluck with the family?

“No, thank you,” said the doctor. “I’ll stop at Bender’s for dinner, and tonight I’ll sleep at Cherryvale.”

He gathered up his reins and urged his fine saddle horse on toward the Benders’, and into oblivion.

Six weeks passed. Leroy Dick may have thought about another township meeting, but did not call it. Along the road traveled something that had the aspect of an avenging army.

For in Fort Scott, Dr. York’s brother wondered about him, even as Dr. York himself had wondered about Longcohr. And Attorney A. M. York was not the man to sit still at home and do his wondering about a vanished kinsman.

A. M. York was forty-five years old in 1873, had served as state senator, and owned a substantial amount of property. He was a man of position and reputation in Fort Scott. A dozen years ago he had gone to the Civil War as a second lieutenant, and for courage and ability had risen to the rank of colonel, commanding a regiment of Negro infantry in the Army of the Frontier. His figure was erect and stalwart, and the mature ruggedness of his features was accentuated by a thick beard, dark and curly. To Independence he rode in mid-April, made inquiries about the brother who had never ridden home, and then started back toward Fort Scott. With him rode fifty friends and neighbors of the lost doctor. They carried weapons.

They paused to speak to residents of Cherryvale. Hadn’t Dr. William York planned to spend the night of March 9 there? But nobody in Cherryvale remembered seeing the young doctor. On the morning of April 24, they rode into Osage Township. Bearded Colonel York — they were calling him colonel and sir, as if he were at the head of a military unit — stopped at house after house to ask about his brother, with all his followers listening in their saddles. He’d been seen in Osage Township, eh? And what was the name of those people with whom he was planning to eat dinner? Bender, was it? It surely was.

Into the Bender yard they rode, and bunched up there like a cavalry patrol.

Young John Bender met them at the front door. One account says that he had been reading a Bible, and stood with it closed upon a finger to mark the place. He answered Colonel York’s questions.

Dr. York? Dr. William York, a nice-looking young fellow on a nice- looking horse? Sure enough, Dr. York had eaten there at noon on March 9. Kate had served him, and she would remember that attractive guest. Leaving the Bender place — yes — it must have been at Drum Creek, yonder across the road, a small stream rimmed and tufted with scrubby trees, that Dr. York had been killed.

“I was there not long ago,” said John, “and shots were fired at me.”

“Shots?” repeated Colonel York. “Who fired them?”

“I never stopped to see,” smirked John, plausibly enough. “But you protect me, Colonel, and I’ll take you there and show you.”

Colonel York beckoned to several of his party. They followed John to the banks of Drum Creek, and John pointed to a cottonwood trunk. Colonel York bent down from his saddle to see. Those holes looked like the marks of bullets. …

“A grave!” John Bender almost yelped, pointing.

The men sprang from their horses, gathering at the mound. It bulged upward, the length and width of a man. At York’s crisp order, two cantered back to bring spades and picks from the house. Then they dug. John Bender, helping, forgot to giggle. A spade grated horribly on bone, and a man exclaimed nervously. Carefully they scraped the earth from white ribs, tagged with rotting flesh. Colonel York gazed stonily, his mouth thin in his beard.

“It’s only a hog,” said one of the diggers.

The skull had turned up on a shovel, long-jawed, shallow-craniumed, the skull of a beast. They covered it again, and rejoined their party in the Bender yard.

The other members of the family had come out on the stoop — William John mystified, his wife uncomprehending, Kate pleasurably excited by the presence of so many men. Colonel York entered the house, with some of his party, and sat at the table. He told his errand. Kate listened with every evidence of sympathy and concern.

When he had finished, she raised her eyes to the roof beams. “I am a spiritualistic medium,” she said slowly. “Perhaps I can help you, Colonel York.”

Sitting down opposite him, she clasped her hands as though praying. Her lips moved soundlessly, her body grew tense and rigid, her eyes closed dreamily. Then she started up, shaking her head.

“There are unbelievers here,” she said accusingly.

Colonel York said with utter gravity that if Kate Bender could find his brother, he would believe in her power forever.

“Return in five days without the skeptics,” she replied. “I will find your brother — yes!” Her voice rose shrilly. “Even if he is in hell!”

The colonel sat silent for a moment, then rose and bowed his thanks. He walked out, followed by the others. Mounting, he led the party away.

He had voiced no definite acceptance of Kate Bender’s invitation to a private seance, and nobody saw him return until he was sent for.

On May 4, shrewd Silas Toles rode up to the door of the Bender house. John was not there to take his bridle, and when Toles dismounted and knocked, nobody answered. Puzzled, Toles led his horse around to the back yard.

In the barnyard he saw the cows and the horses. They moved around, weakly and wretchedly. At a glance he saw that they were famished. At once, he drew water at the well, and watched them drink greedily. Then he went in at the rear door, calling aloud for Mr. and Mrs. Bender. But nobody was there.

Toles summoned other neighbors. A man rode at a gallop to send a telegram to Colonel York in Fort Scott. On the following day, May 5, York arrived, with a friend or two. Toles and others met him in front of the Bender house.

“It’s another disappearance,” said Toles, and York nodded silently. He took charge of the situation. They followed him into the front room, around the canvas partition and in among the unmade beds and dirty dishes. Near the mid-point of the canvas, York stooped and picked up something. It was a heavy sledge hammer.

“See how the light shines through that canvas,” he said evenly. “Right here, opposite where I’m standing, is the bench where a guest would sit. If Kate said something to make his head press back against the canvas, and somebody stood here — probably the old man, he was big and strong —”

He swung the sledge against the canvas, and dropped it on the floor. His silent companions stared sickly at each other. But Colonel York was striding back into the front room. “Pull that table out,” he commanded.

It was done. Kneeling, York pried at the floor boards. A section of them rose up like a trapdoor. Someone held a lantern down into the darkness, and they could see a pit, six feet across and nearly as deep. A sickening stench rose. The earth was gummy with clotted blood.

“Then they would open the trap,” continued York, in the same quiet, confident voice. “They would hold their victim above it and cut his throat. They would hide his body there until night, when they would drag it out, rob its pockets, and carry it away to bury it.”

“Bury it?” repeated someone.

Colonel York went outside, still followed by his companions. He paused to draw from the tail gate of a dismantled wagon a long thin rod of iron.

Then he paced in among the trees of the orchard, thick with pink and white springtime blossoms. He seemed to measure, to judge, the harrowed earth around their roots. Finally he thrust the rod deep into the soil. When he drew it back, they could see a tuft of hair at its tip.

“There is where my brother is buried.”

More people had been gathering around him. A digging party set to work. Meanwhile, the colonel walked away under the trees. Again and again he stopped to probe. By the time the first hole had been dug to five feet, he had indicated the positions of half a score of graves.

They called him back to where they had uncovered a half-naked human corpse. He gazed into its rotting face, and nodded.

“That is my brother,” he said.

The busy spades turned up ten other bodies — eight men, a woman, and a little girl. The missing Longcohr and his daughter lay in the same grave. She had been strangled. All the others had died of smashing blows on the head, or of cut throats. One by one the bodies were identified, then and later. Some of the men were known to have carried large sums of money.

The searchers glared at the pitiful bodies, and at one another. A community interest in vengeance swelled among them. For some minutes Rudolph Brockman, who had helped uncover the graves, was threatened with lynching for no better reason than that he, like William John Bender, spoke with a German accent. Then his neighbors turned from him, and organized quickly into four posses, to scour the country in all directions. They returned from their missions — very soon, indeed, for manhunters, it was remarked — to report that the Benders left no trail whatever.

Still later, several bodies were found buried near Drum Creek. It was rumored that as many as forty other victims of the Benders were never found.

And that is the end of the official history of the Benders.

For decades afterward, efforts were made to explain what happened to them. Several persons broke into the news from time to time, either claiming to be the Benders or charging others with that baleful identity. The most plausible of such reports led to the arrest, in the autumn of 1889, of Mrs. Almira Griffith and her daughter, Mrs. Sarah Eliza Davis, in Michigan. They bore striking resemblances to Mrs. Bender and Kate, and were tried in Labette County for the murder of Dr. York. Their able defense counsel, John T. James, offered such convincing evidence of mistaken identity that the prosecutor moved for dismissal of the case.

At about the time of the outbreak of World War II, a vague rumor spread in Kansas that Kate and her brother John still lived, two old and feeble paupers, in widely separated parts of the country. No official took this tale seriously enough to go hunting for them.

Did, then, the Benders escape unpunished, to enjoy their bloodsoaked plunder? They did not, official opinion to the contrary notwithstanding.

There are at least three solemn and definite avowals by men who claim to have helped kill the entire Bender family.

Two of the three accounts are deathbed confessions and, as such, merit respectful notice. Living, a man may have a host of reasons — hope of gain, revenge, thirst for notoriety — to lie, but when he is dying, with no prospects but the grave and what may meet him beyond, his impulse generally is to tell the truth. In courts of law, deathbed declarations are given much weight.

When George Downer’s doctors pronounced him mortally ill in 1909 at his home in Downer’s Grove, the Chicago suburb named after his grandfather, he wanted to ease his soul of a secret too heavy and fearsome to carry to the eternal silence of the grave. In his last hour he summoned a lawyer and some friends.

Haltingly, he told them that as a young man he had lived in Independence, Kansas, and that in April of 1873 he had joined Colonel York’s search party. He had helped, he said, to capture and kill the Benders. As he talked, his strength and voice failed. Mrs. Downer sat beside his bed and told the tale of blood as she had heard it from her husband years before. Feebly Downer spoke from time to time, prompting or correcting. As she finished, he closed his eyes and died. His statement was put into written form and the witnesses swore to it.

A year later, in 1910, a man named Harker or Hooker also lay dying in a New Mexico cow camp. Like Downer, he told friends of hunting down the four Benders, and described in some detail what happened after the killing. He and his companions had gathered around the four bodies, decided that it had been an execution without due process of law, and that the deed might be called murder and punished as such. Wherefore they buried the Benders and obliterated all traces of digging. The sum of several thousand dollars, found on the bodies, was divided among the self-elected avengers. Then, with bared heads and raised hands, they had sworn to one another and to God never to tell what had happened.

Harker asked that his confession be repeated to relatives in Kansas. His fellow-cowmen brought the story to Labette County.

Attorney James, who had represented Mrs. Griffith and Mrs. Davis at their trial in 1889, had maintained an unflagging interest in the half-told Bender saga, and through the years he gathered all available material for a history of the case. This he published at his own expense in 1913, in a modest-appearing little book entitled The Benders in Kansas, printed at Wichita. He noted both the Downer and Harker statements, but was inclined to accept a story that the Benders had been seen on a train bound for Texas. His book aroused surprisingly small comment, but it may have contributed to the determination of another Kansas historian to search for yet more evidence.

Mrs. Edith Connelley Ross of Topeka, daughter of the late William Elsey Connelley, Kansas’ foremost historian, was herself a devoted student of her native state’s early annals, and for some years she tracked down hints and rumors about the Benders. In 1928 she prevailed on a pioneer Kansan to tell his own version of the hunt and kill, and wrote an account which is now in the files of the Kansas State Historical Society.

This old man, a lifelong friend of the Connelleys, first swore Mrs. Ross to withhold his name, and this she has done. Neither verbally nor in writing did she ever identify him, saying only that she had absolute faith in his honesty and truthfulness.

He told her that when Colonel York left the Bender house on the afternoon of April 24, the entire party was convinced that they had found the murderers, but that they lacked evidence to convict. York dispersed the band, but quietly told several discreet and trusted friends to return with him after dark the same night. Both Downer and Harker, incidentally, were among these. He led them to the house. They entered and took all four of the Benders captive. Then the questioning began outdoors.

Very little imagination is needed to conjure up a vivid picture — a dark night in early spring, the gloomy prairie stretching far away in all directions to the star-strung horizon, the group of stern frontiersmen with guns at the ready. Colonel York was an accomplished courtroom lawyer, a veteran officer of harsh campaigns, a man of deep family feelings who was determined to find and punish the murderers of his young brother. His face must have been a bearded mask of nemesis as he shot out his questions at one captive, then at another. In him were combined the canny cross-questioner, the seasoned warrior, the righteous avenger of blood. Before his probing queries and fierce charges the Benders, so terrible to unsuspecting and defenseless victims, lost their glum pose of innocence. They fell into contradictions. They made damaging admissions upon which York pounced. They cringed and trembled.

They blurted out all that the inquisitor wanted to know, hoping to move him to mercy. They pleaded and prayed.

At York’s command, the guards stepped away from where the four captives huddled together — Kate’s rosy face pale, her lovely eyes staring; young John’s lips twitching over a nervous snicker; the burly father sagging, snarling; the old mother shaking like jelly. Then a dozen rifles spoke at once. The horses started and reared, their holders swung on the bridle reins. And spades began to bite the earth, hollowing a grave to be big enough for four.

Who would hear that volley, miles away from law-abiding houses? And the place of that markless grave, well back from the road, might not be passed again for a year or more. By then, the buffalo grass would be rooted upon it. The prairie flowers, gold and blue and white, would turn up their guileless faces to welcome another spring. Nobody would recognize the gentle swelling of earth for the resting place of bloody, degenerate murderers, dreadful even on a frontier whose history is clotted with gore, stirred with violence.

In Labette County today live a few oldsters who were little children when, in 1873, their fathers rode with Colonel York to find news of his lost brother. Go there among them. Talk to them about the Benders. They may seem too polite, too age-mellowed, to argue. They may nod, as in agreement, when you say that official records indicate that the Benders escaped.

But even if they won’t say so, they know what happened.