The Murder in Room 406, 1925, Boston

Home | Feature Stories | The Murder in Room 406, 1925, Boston

Originally Titled: “The Crime in Room 406,” by Sgt. Thomas Harvey, as told to Fred H. Thompson, True Detective, Sept. 1930.

Want to Read This Story Later On Your Tablet?

Download PDF file of The Murder in Room 406

.

“Something terrible has happened over at Hotel Hollis!”

These were the words that greeted me when I reported for duty on the morning of May 31st 1925, at Division 4 Station House on Lagrange Street [Boston, MA]. The speaker was a youth I recognized as one of the bellboys at Hotel Rollin, located nearby on Tremont Street and patronized by theatrical people. His face was ghastly, and he was trembling like a poplar leaf in the breeze.

“What is it?” I questioned

“It—it looks like murder!” gasped the bellboy.

I called a patrolman to accompany me and took the frightened youth back to the hotel. At the entrance encountered the room clerk, and the manager, James Reagan. They too, appeared white and shaken. After what I saw a few minutes later I felt a little pale myself. In my years of police work I have seen and investigated many strange and horrible crimes, but the “Hotel Hollis Mystery,” as this case became known in the trying days that followed, stands out in my memory as one of the most brutal and difficult of my

A few quick questions and I had learned enough to order the officer with me to hold everyone in the hotel. Then I went up to Room 406. Clustered in the hallway around the door was a group of frightened employees and guests. I stepped into the bedroom.

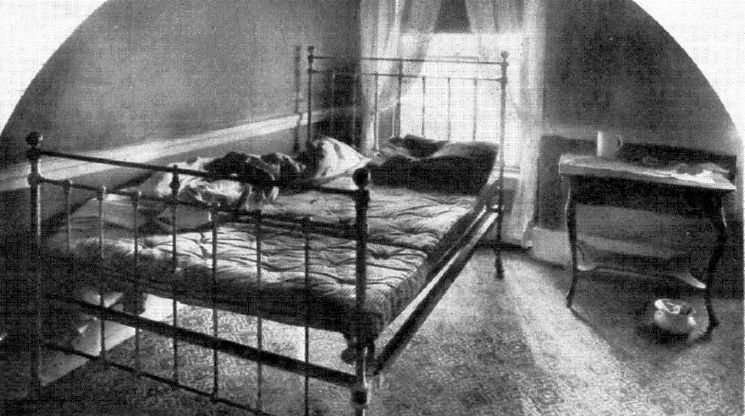

Face-down on the bed was the body of a woman. Her arms were drawn behind her back and bound together with strips torn from the bed sheets. The disarranged bedding suggested a fearful straggle. Above her rent and die.-beveled night-dress I saw on her neck dark discolorations and scratches. Blood from her mouth stained the pillow; into which her face was deeply pressed.

I touched the body. It was cold. I knew then she had been dead several hours. Obviously, she had been murdered. My job was to find the murderer, but first there were certain routine things to be done. Nothing could be disturbed until the medical examiner had made his inspection.

I telephoned a brief report to the station house and arranged for Inspector James A. Dennessy, head of the homicide squad at police headquarters, to be notified. I then telephoned the district medical examiner, Doctor Timothy Leary. Other officers were hastily sent over front the station house and I placed them and ordered everyone in the hotel held. While awaiting the med. kal examiner and Inspector Dennessy, who soon arrived with a police stenographer, I learned these facts:

The dead woman was Mrs. Mae Prior, wardrobe mistress of the “Brown Derby” theatrical company, which had closed its run at a Boston theater the previous evening—it was now Sunday morning. She had retired to her room alone around midnight, or shortly thereafter, planning to go to New York with other members of the troupe on the noon train Sunday. When she did not respond to repeated telephone calls to her room that morning, a bellboy had been sent up to awaken her. He found the door ajar and looked in. What he saw sent him racing back to the hotel desk with the alarm, and then over to the police station to get me.

The deep indentation in the pillow where Mrs. Price face was pushed into can clearly be seen in the above photograph. With blankets over the mattress, the killer hid under the bed until the victim returned and waited for her to fall asleep.

Be Sure To Follow Us on Facebook for Weekly Updates, New Stories, Photos & More

Cool, skillful, experienced Doctor Leary began his expert examination. His keen eyes seemed to take in everything at a glance. “She certainly put up a good fight,” he told us.

When he turned the body over, the face and chest showed that the woman had received a fearful beating. Some of the ribs were fractured. Wide bruises on the throat and the protruding tongue told that the unfortunate woman had been strangled. After a thorough examination of the marks on the throat, the medical examiner said: “Look for a person with extra large hands.” That was the first real clue we had found. Then he made what seemed to be an important discovery. Under the dead woman’s well-manicured fingernails was what appeared to be bits of human skin and dried blood. Laboratory examination later confirmed this.

We now believed we had two clues of the greatest importance. The face or hands of the murderer would be marked by fresh scratches. And, the murderer had unusually large hands.

Mrs. Price’s clothing, toilet articles and other belongings were placed about the room in a natural manner, evidently as she herself had left them. On the floor near the bureau, was a small envelope, the sort used as a pay envelope, one end torn off and dropped nearby. The envelope was empty. In a box we found a similar envelope containing a five dollar bill and some change. The only signs of a struggle were confined to the bed, and we agreed that the murderer had surprised the victim while she was asleep or there was another possibility.

The bellboy who reported the crime that morning about 9:30 claimed that he had found the door of the room ajar. Was the murderer someone Mrs. Price knew and trusted; someone that might be permitted to enter her room after she had retired for the night? Was the motive jealousy or revenge, or was it robbery? Or was there something behind this sordid crime we had not yet guessed?

Under the bed I saw a partly smoked cigarette. This might be a clue. Had the murderer been hiding under the bed while waiting for the moment to strike?

Every person in the hotel was questioned before anyone was permitted to leave. Some of the guests protested against their detention, but it was necessary and we didn’t intend to take a chance that the murderer might slip out of the police net we had thrown about the entire establishment.

Some of the members of the “Brown Derby” company were at other hotels, and the manager of the show was registered at the Arlington Hotel. We rounded them all up. After our thorough questioning of everyone who might have any helpful information, we bad found no one who admitted seeing any person enter or leave Room 406 between the time Mrs. Price retired and the discovery of the crime by the bellboy that morning. No one admitted having heard a sound of the frightful struggle we believed had occurred after mid-night and before 2 A. M. The medical examiner assured us that Mrs. Price died about 2 A. M.

The condition of the body and the mute evidence of the bed fairly shouted the story of the desperate battle for life the unfortunate woman had made. Yet none of the guests in adjoining rooms, none of the hotel staff, had heard a sound to arouse suspicion!

We found something to strengthen the robbery theory. The show manager said the torn envelope had contained $80, Mrs. Price’s pay given her the previous evening.

Members of the company said Mrs. Price was the “mother” of the show and took charge of small sums of money for the younger girls. A Jewish boy in the cast had been befriended by her, I learned, and he had given her $60 to save for him. In all, it appeared, Mrs. Price had about $200 in her possession. But we had found in the room only the five dollar bill and some small change!

This young man who had given Mrs. Price $60 for safe-keeping aroused my particular interest.

He felt for her the affection of a son, he insisted. I also was interested in the information that the murdered woman’s husband was a stage carpenter, employed in New York City. He was Bill Price, we learned, and worked in a theater at Broadway and 91st Street. This information was telephoned to the New York Police, with the request that the husband be located and the news of his wife’s death broken to him.

We soon had word from New York that Bill Price had been working there Saturday evening until nearly midnight. News of his wife’s terrible death was a great shock to him and he was coming to Boston on the first train Monday morning to aid in the search for the murderer and to claim the body.

I liked Bill Price on sight. He took his wife’s death hard, and I felt mighty sorry for him. But I learned nothing that brought me any nearer the moment I was yearning for, the chance to slap the handcuffs on the murderer.

Well, several days passed” and the police investigation seemed to be getting nowhere. Inspectors from headquarters, plain-clothes men, an army of newspaper reporters and plenty of others were looking for clues, and, there were plenty of alleged clues turned in, but all proved worthless after a painstaking investigation.

Anonymous letters came telling us to look up this person or that one. Several characters who hang around the South End were named to the police in this way as the wanted murderer. Not one of these possibilities was overlooked. Every lead we followed led us to the same thing – exactly nothing.

One by one the inspectors were taken off the case for other jobs, but my superiors kept me plugging away. I was working night and day, going over the same ground again and again, racking my brains for the solution of a crime that at the start-off had looked like an ordinary, routine case. Nothing seemed to break.

“It’s just one of those cases that can’t be solved,” an Inspector told me.

I spent a lot of time around the hotel, talking with the guests who were still there and with the employees, searching for the lead I kept telling myself must be somewhere if I could only find it. Some of the folks who were there the night Mrs. Price was murdered might be–well, surprised to put it mildly, if they knew what a lot of miscellaneous information I casually picked up about them in the course of my intensive inquiry. On Tuesday, June 2nd, I recall, I heard that a theatrical man occupying Room 606 with his wife gave a birthday party after the performance on the evening of May 30th, and was making merry with his friends at the very time that Mrs. Price was fighting for her life in the corresponding room, just two floors below. I found out who attended this birthday party and interviewed every one of them, on the off chance that something was seen or heard by somebody that would give me a clue. The man who gave the party told me about an odd thing that happened that night, but which apparently had no connection with the murder.

He said that when he ushered his friends into his room after the theater, he left his door key on the corridor side of the lock. When the party broke up and he and his wife were preparing for bed, he couldn’t find the key and decided it must have fallen out, and that someone had picked it up and turned it in at the hotel desk. So the door was secured with the inside bolt. Sunday morning he told the room clerk about it, but the key had not been turned in and he was furnished with a duplicate.

Miss Mae Jensen, a vaudeville actress who had a room on the top floor, was the only person I found who remembered seeing anyone acting in what might be a suspicious manner in the hotel the night of the murder. She told me that around mid-night she was on the way to a friend’s room to borrow a razor, and was accosted in the corridor by a large, rough-looking man. Miss Jensen said she supposed it was a would-be masher [a man who is aggressive in making advances towards women], but something about the man’s manner so frightened her that she dodged back into her room and locked the door. Mrs. Price’s room was down on the fourth floor, so Miss Jensen’s adventure looked like a rather remote possibility as a clue.

Saturday afternoon, June 6th, I decided to try something new. I believed I had exhausted every possibility in the hotel and among the guests and employees, and the crime was still unsolved. Room 406 and everything in it had been thoroughly examined for fingerprints without producing anything of value. I considered the possibility that one of the questionable characters frequenting the district might be able to give me a good tip. It was a thousand to one shot, but the case had been getting more discouraging every day and I was ready to try anything. If the motive for the crime was robbery, the murderer had made away with around 200. I wondered if I could find some tough egg around the district who had become suddenly affluent.

Near the hotel I saw a young fellow I knew. He was a bum actor who associated with underworld characters of the cheaper sort.

“I want to see you,” I told him. “Meet me on Dillaway Street in ten minutes. Be sure to be there.”

I rather doubted the possibility of his showing up, but I knew it would be useless to try to get anything out of him I saw the young fellow was getting nervous and trying to edge away. I guessed he-was afraid-Someone would see him talking with me, and he didn’t want the gang to think he was a “stool” there in the main street, where his questionable friends would see him talking to a police detective. So I acted as if I were merely passing the time of day with him and kept my voice too low to be overheard by any bystander.

In ten minutes I walked through Dillaway Street, a quiet, side street, and found the young fellow in a doorway, waiting, where he was screened from observation.

“I’ve always been on the level with you,” I opened up. “Give me the office. Who bumped off that woman in Hotel Hollis?”

“Look for that big gorilla that was hanging around the hotel last week,” he blurted out, after hesitating a moment.

“Who is he?” I asked the fellow. “Where does he hang-out?”

“Don’t know anything about him.”

“How do you know this gorilla did it?”

“I don’t. You wanted the office and I thought of this big gorilla, so I just told you about him.”

“Who’ve you seen this big gorilla talking with?” I persisted. “Come on, you must have seen him speak to somebody? Who?”

“Well,” the fellow told me, “I remember one night last week I saw him stop to speak to a man I know. It was in front of the hotel. Benny Perretti was the man he spoke to. Benny was doing a tum at the theater here until Thursday, and now he is playing down in Newport, Rhode Island, and commuting back and forth to Boston.”

This tip looked pretty slim, but I was desperate and I couldn’t afford to pass anything up. So I went to work to locate Benny Perretti. I learned he was staying at the New Tremont House and usually got in around mid-night. But before he left for Newport, I heard, he might be found sitting around Boston Common. I failed to find him around town, so I went to the New Tremont House to wait for him.

He came in late with his partner. I wanted a chance to talk with him alone, so I arranged for him to meet me at the police station Lagrange Street at 7:15 -the following morning. The rest of the night I spent hunting around to find out something more about the man described to me as a “big gorilla.” ,

Benny Perretti met me at the station house on time. In answer to my questions he finally told me he knew the man I meant. He said the fellow tried to borrow some money from him sometime during the evening of Memorial Day.

“I was with some fellows in front of Hotel Hollis,” he told me. “I don’t know the man’s name. I only know him by sight.”

“Where did you meet him first?” I persisted. “How did you get acquainted with him?”

“It was once when I was putting on a show for the prisoners at the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth,” Benny Perretti told me. “They called him ‘The Wop’ out there.”

That didn’t sound just right, so I went after Benny pretty hard, and he finally told me he was a prisoner himself when he, met this big gorilla he called “The Wop.”

The story I finally got was this: Benny and his stage partner were young, fellows just getting started at the time they got into trouble. A trunk was delivered by the express company to their room by mistake, but they didn’t say anything and when the mistake was discovered they were arrested and prosecuted in the United States Court because the trunk came from another state and so it was an interstate affair. The two boys had no money for a lawyer, and were so frightened and inexperienced they pleaded guilty, thinking they would get out of it. However they were both given terms at Leavenworth.

Benny Perretti said the man he knew only as “The Wop” was in Leavenworth, and was such a bad actor he was kept locked up most the time. Benny told me that one time “The Wop” escaped from Leavenworth by crawling through a sewer pipe, and was caught and brought back in a few days. He said he hadn’t seen or heard anything of him until a week before, when the ex-convict accosted him and asked for money.

Superintendent of Police Michael Crowley rushed a special delivery letter to Leavenworth for a picture and all available information about the prisoner who had escaped through a sewer pipe at the time Benny told me the incident occurred.

The answer came June 14th. In the meantime, I had been hustling on the investigation as hard as ever, but didn’t turn up any other lead.

The letter from Leavenworth said the man known as “The Wop” had served a long sentence for robbery under the name of Frank Corey. I took the Leavenworth picture to the Rogues’ Gallery at police headquarters and picked out half a dozen more pictures that were as similar as possible. This bunch of pictures I showed to Miss Jensen. I spread them out on the table and asked her if any of them was a picture of the man who accosted her the night Mrs. Price was murdered and frightened her so badly she ran into her room and locked the door.

“That’s the man. I’m sure of it,” the pretty vaudeville actress told me. She was pointing to the picture of Frank Corey from Leavenworth.

Benny Perretti had left Boston in the meantime to play an engagement in New York. I took the pictures to New York and snowed them to Benny. He picked out the same picture Miss Jensen had.

“That’s “The Wop,'” Benny told me.

I hadn’t a thing to connect this federal ex-convict with the murder. I was just playing a hunch. I hadn’t any idea where he lived or what had become of him, either. Superintendent Crowley was backing me to the limit and he expected me to make good. He sent another rush message to Leavenworth and asked for the names of anyone Frank Corey had written to while serving his sentence.

We knew that such records are carefully kept at modern prisons. We were given three names and addresses, in Yonkers, New York, in New York City and in Worcester, Massachusetts.

I went to Yonkers first and found the person “The Wop” had written to from Leavenworth was dead. Then I looked up the New York City address. It was on West Forty Second Street and I found it was a maternity hospital. No one in this institution knew anything about the man I was hunting for.

I got a New York police detective to help me, and we started checking the number Leavenworth officials had given on every street on the West Side from Thirty Second to Fifty-Second. We hunted up the letter carriers too, but nobody had ever heard about any Frank Corey or the person whose name had been supplied by Leavenworth as that of someone the convict bad written to in New York.

Then we tried the East Side as a last resort. It was mighty hot and muggy in New York that week. I was nearly worn out by the long grind and lack of sleep. The detective with me finally quit to get some rest. I decided to try one more street and then knock off for a little while myself. A kid was eating a banana in a doorway. I started in there and slipped on the banana skin, fell and nearly broke my back.

This was on East Forty-Second Street. I was sweltering and my hurt back was throbbing, but I forgot my discomfort a few minutes later when I bumped into a woman who said she recognized the picture of Corey as a man who had been living next door with a Polish blonde. The woman said the couple were there several years before and that they had “cleaned out” the landlady and escaped with the loot.

The way I got the story it appeared the Polish blonde was the woman Corey wrote to from Leavenworth and he had joined her in New York after he was released.

WELL, the breaks were still against me, for the house next door had just been razed! I located the realtors and got the name of the trustee in a bank who had handled the sale for the landlady. I saw him and learned the landlady had just died. This looked like the end of the trail in New York. I couldn’t find anything more there, and so I came back to Boston on June 21st, and went to the station house to write my reports, feeling pretty discouraged. .

The Superintendent had a talk with me. I told him there was still one more possibility-the address in Worcester. He told me to keep at it; he thought my hunch looked good. So I went to Worcester the next morning and called at the Worcester Police Headquarters to tell my story and get a detective to go with me. The address I had was “Corey, 934 Grafton Street.”

On the way out there we met a motorcycle officer who told us the family at this address was named Krecorian and used the American name Corey. I showed him the Leavenworth picture and he said: “Sure, I know that felllow. That’s Frank Corey. I was talking with him this morning. There’s sewage draining into the road from the Corey place and I told them it must be fixed.

THIS gave us an idea. We arranged for the detective to take me into the house as an inspector from the Health Department, so I could talk with Frank Corey and get him down to Worcester Police Station for questioning without arousing his suspicion.

There was a crippled girl in the house who said her brother Frank Corey had gone in town and would soon return on the trolley car. While the detective with me was talking about the sewage complaint, I saw a picture on a table of the same man I knew to be Frank Corey, ex-convict from Leavenworth. I slipped it into my pocket without anyone noticing, and then we left the house.

It was arranged, for the motorcycle officer to go up the road to wait for the trolley, and see if Frank Corey was on it. I hid in the woods where I could watch without being seen, and the Worcester detective went to telephone. If Frank Corey was the man who killed Mrs. Price, I knew he would be on his guard and I didn’t want him to slip away from us.

Presently, the motorcycle officer came back and said the man we were after was on the trolley and would soon be home. We started walking along the road and just as we got to the Corey house a big gorilla-like man turned into the yard. It was Frank Corey, the man I had been hunting for more than two weeks.

We used the Health Department gag and it worked. Frank Corey agreed to ride down to Worcester Headquarters and get the sewage complaint fixed up.

On the way he said: “Gee, you fellows hound a guy.”

When he was safely in the police station, I asked him: “‘When were you in Boston last?”

“I was never in Boston in my life,” answered

“Do you know the Hotel Hollis?” I asked him then.

“Never heard of it,” Corey declared. “I was never in Boston in my life.”

“You know the ropes,” I told him, “you don’t have to talk if you don’t want to. Do you know Benny Perretti?”

“Over in Leavenworth Penitentiary,” said Corey.

I showed him his police picture and asked him: “Is this your picture?”

“That’s not my picture,” the man denied.

I told him he was under arrest charged with the murder of Mrs. Mae Price.

Everything he had said and our questions had been written down and I asked him to sign the statements he had made.

Corey told me: ”I’ll talk but I won’t sign anything.”

He was locked in a cell and I telephoned a report to Boston police headquarters. I was told that Captain Goodwin, my “skipper” at the Lagrange Street Station, would come to Worcester in a police car and get the prisoner.

In the meantime, Worcester police discovered they had a record of Corey. I learned he had been arrested a short time before on a charge of stealing a check and a bracelet. He agreed to make restitution to the plaintiff and was released. I found he had made restitution shortly after Mrs. Price was murdered.

While Corey was locked up in Worcester after I had questioned him he succeeded somehow in getting word out, and a lawyer came and told him not to talk. It was the same lawyer who represented him in the case where he had made restitution. The prisoner wouldn’t say another word after that. He was as mum as an oyster when we took him to Boston for arraignment in court. The grand jury indicted him for murder in the first degree and I worked up what I thought was a pretty convincing case for the trial.

I recovered the bracelet he had in stolen in Worcester, getting it from a man he had pledged it with for a loan. A Polish boy in Worcester told me that Corey had a big roll of bills when he came home early in June, and sent the boy to the store to buy a Boston newspaper. A clerk at Hotel Hollis identified Corey as a man who paid $1.50 in advance for room 512 on the night of May 28th.

The clerk said he used the name Frank Mulleono and registered again the evening of May 30th, but was not assigned a room because he attempted to pay for it with a check for $5 written with a pencil and which the room clerk refused to accept. Miss Jensen identified the prisoner as the man who accosted and frightened her on the top floor of the hotel the night Mrs. Price was killed and robbed.

The district attorney was satisfied with the theory of the crime we worked out, and it looked mighty good to me. I believed Corey had been lurking on the sixth floor of Hotel Hollis, where he accosted Miss Jensen, and that he took the key from the door of room 606 and used it to get into room 406, where he hid under the bed to wait for Mrs. Price. When we arrested him he had a package of cigarettes of the same brand as the partly smoked cigarette I found under Mrs. Price’s bed.

My theory was that Corey started to light up while waiting under the bed, and realizing that the smoke might betray his presence when Mrs. Price came in, he hastily extinguished it after one or two puffs. I believed he was there under the bed when Mrs. Price entered the room, put her money on the bureau, undressed and got into bed. Then when he supposed from her breathing the woman was asleep, he crawled out and was detected while securing the money. My evidence indicated that Corey grabbed Mrs. Price by the throat to prevent her from screaming, and was severely scratched on the hands and face during the desperate fight the unfortunate woman made to save her life.

A man answering Corey’s description, I eventually discovered, had visited a nearby drug store the day after the crime to get something for several severe scratches on his face. Worcester witnesses said Corey’s face and hands showed some marks when he came home early in June.

There was one mark on his face when we arrested him, almost healed, that he said was a cut from shaving.

Corey’s family spent about everything they had in his defense. He had a smart criminal lawyer, and there was a long-drawn-out trial. The jury was out for hours and finally came in with a verdict of acquittal.

I was amazed and bitterly disappointed, for I felt certain the man was guilty. So did the district attorney. We had learned that Corey had once deserted Iron the United States Army. This gave me the chance for another effort.

I arranged for the Federal authorities to lock Corey up as a deserter while I did some more work on the case. A curious thing had happened during the trial. A conversation I overheard in the courthouse between two men indicated that Corey had gone to a room on Hanover Street after Mrs. Price was murdered.

AT the murder trial we had not been able to show any of Corey’s movements after the murder until he arrived in Worcester two days later. I succeeded in locating the room in the Crawford House Annex where Corey had gone shortly after the crime, following the clue from the conversation I had overheard at the courthouse. I found he had appeared there early in the morning of May 31st with money to pay $2.50 for a room. Corey wasn’t satisfied with the $2.50 room and after seeing it he changed to another room for which he paid $3.50.

I discovered he was wearing a raincoat when he came in, and had left it there. I recovered the raincoat, and this coat was later identified by Miss Jensen and others as the one he was wearing at Hotel Hollis.

For a long time the trail seemed to end at this Hanover Street room, but I wouldn’t quit. Finally, I placed him the next night at Boston Tavern, the night of May 31st, 1925. The register confirmed the other evidence I secured, that Corey came there the night of May 31st with a woman companion and paid $6 for a room.

The case now seemed ready for the next step we had been secretly planning. The evidence was presented to the grand jury and a secret indictment was returned against Frank Krecorian, alias Corey, alias Costello, alias Mulleono, charging him with robbery of Mrs. Price in Hotel Hollis.

I went to Camp Devens, Massachusetts with the indictment warrant, and the Federal authorities delivered the prisoner to me.

There was a sensational trial.

Frank Corey was defended by the same astute criminal lawyer, but this time the jury found him guilty, guilty of robbing the woman of whose murder he had been acquitted. The defense lawyer claimed Corey was being placed in double jeopardy and appealed to the higher courts, but was overruled.

Judge Lourie sentenced Frank Corey to life imprisonment. He declared the crime was one of extreme atrocity, praised the jury for its intelligence, and intimated he was imposing the unusually severe sentence for robbery because of the unexpected outcome of the previous trial for murder.

Download PDF file of The Murder in Room 406

Be Sure To Follow Us on Facebook for Weekly Updates, New Stories, Photos & More

—###—

True Crime Book: Famous Crimes the World Forgot Vol II, 384 pages, Kindle just $3.99, More Amazing True Crime Stories You Never Knew About! = GOLD MEDAL WINNER, True Crime Category, 2018 Independent Publisher Awards.

---

Check Out These Popular Stories on Historical Crime Detective

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, January 15th, 2014 under Feature Stories.

Tags: 1920s, Massachusetts, Women