Feature Story: Murder, Masonry, and Popular Justice in Gilded Age Indiana: The Trial of the Reverend William F Pettit

Special Guest Feature Story by: Dr. Barry Morton: Dr Barry Morton is a historian who specializes in investigating the activities of corrupt and fraudulent religious figures including many self-styled “prophets” and “faith healers”. A resident of Crawfordsville, Indiana, he found references to a notorious 1890 murder committed by a prominent local Methodist minister many years ago. Understandably drawn to the details of the case, he was initially unable to find reliable information relating to the case. After spending many months tracking down elusive sources of information in local newspapers, church archives, and court basements, he was eventually able to resurrect the scandals surrounding this vicious and cruel poisoning. A full-footnoted version of this article can be viewed at Academia.edu

At few times in its history has the small town of Crawfordsville, Indiana ever been more regularly in the spotlight than it was between the autumn of 1889 through November 1890. The Pettit murder trial, “the most publicized case in this period,” began with published rumors of the Reverend William F Pettit’s suspicious conduct around the time of his wife’s death in August 1889, continuing through grand jury deliberations and his arrest in early 1890. His lengthy and dramatic trial, held in Crawfordsville between October and November 1890, “attracted attention throughout the Midwest because of the prominence of the families involved in it.”

The Pettit murder attracted widespread attention for two good reasons. On the one hand it was the lurid nature of the case: “the murder for which Pettit stands convicted was one of the most deliberate, cruel, and cold-blooded crimes ever committed in the state of Indiana.” The courtroom was packed daily and local spectators lined up every morning with their own chairs. Even Lew Wallace, the author of Ben Hur and the town’s most famous resident, was in regular attendance (and said to be writing a novel based on the case), as were journalists from Indianapolis and Lafayette—whose stories were reprinted widely.

In addition, the prominent social position of the murderer and his accomplice made it equally dramatic. Not only was Pettit the minister of one of Indiana’s wealthiest Methodist congregations, but he was also one of the highest-ranking Freemasons in the state. His accomplice, the widowed Clemmie Whitehead, came from an upstanding family—the Meharrys—that was easily the wealthiest in the Montgomery and Tippecanoe County area that its landholdings straddled.

The entire Pettit affair also illustrates the tension that existed in America’s evolving justice system. As the legal scholar Elizabeth Dale has so deftly shown, America’s justice system was an evolving, contested arena well into the twentieth century. Even late into the nineteenth century, local notions of popular justice coexisted with the distant, bureaucratic arm of the state. For instance, in western Indiana, the vigilante Horse Thief Detective Agency had a far greater presence than the various county sheriffs and local police. While the vigilantes did not get involved in the Pettit affair, the actions of ordinary citizens were decisive in first obtaining official prosecution and then conviction. Gossip and shaming were central to the affair, and these were classic forms of popular justice. The people of Shawnee Mound were convinced of Pettit’s guilt, but believed his station would enable him to get away scot-free. Their actions, which he sought to counter, led to his demise.

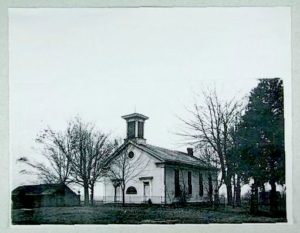

If the Pettit murder trial was one of the major events in Crawfordsville’s history, the details surrounding it are not always simple to uncover. The Shawnee Mound community, formerly a densely-settled agricultural area, now has few residents in this era of mechanized farming. The Shawnee Mound Methodist Church, which once had a large and wealthy congregation, was shut down some eighty years ago and the building destroyed. Most official records relating to the case, including a 2,000-page prosecutorial set of notes and evidence, were destroyed. Oral traditions in the Meharry family, which still has a minor presence in the area, relate information that cannot possibly be true. Church and Masonic records related to the case are also remarkably thin. Fortunately, the ongoing emergence of America’s digital history infrastructure makes it possible to reconstruct the case for the first time.

The Protagonists

Four individuals are crucial to the understanding of the case.

Hattie Pettit

The murder victim, Hattie Sperry Pettit, seems to have been a true innocent. Born into a religious, middling, Oswego County, New York, family, she became a schoolteacher in adulthood. Described as “not beautiful” but kind and highly intelligent, she was a well-liked figure wherever she went. Shortly before leaving to take up a better-paying appointment in South Bend, Indiana, she met her future husband at school as well as at revival meetings he was holding. Following her move in August 1880, they decided to get married, and he moved to South Bend to join her. She obtained a teaching job for him, which he soon discarded, preferring to work instead in the collections office of the Studebaker factory. She continued to teach after the birth of her only child, Laura Aldine (Dine) in 1882.

The murder victim, Hattie Sperry Pettit, seems to have been a true innocent. Born into a religious, middling, Oswego County, New York, family, she became a schoolteacher in adulthood. Described as “not beautiful” but kind and highly intelligent, she was a well-liked figure wherever she went. Shortly before leaving to take up a better-paying appointment in South Bend, Indiana, she met her future husband at school as well as at revival meetings he was holding. Following her move in August 1880, they decided to get married, and he moved to South Bend to join her. She obtained a teaching job for him, which he soon discarded, preferring to work instead in the collections office of the Studebaker factory. She continued to teach after the birth of her only child, Laura Aldine (Dine) in 1882.

Hattie was unhappy from very early on in her marriage, and met fairly frequently with Methodist Pastors to discuss this problem. “She said her home was miserable and he [Pettit] was breaking her heart.” A major source of her unhappiness were her husband’s frequent attendance at Masonic Lodge meetings, and his continued late-night carousings “with boon companions” that he met at them. Viewing her husband’s occupation as a cause of his behavior, she implored the Rev Hickman, to obtain a post for her husband as a Methodist Preacher. Hickman spoke to Pettit, telling him that he was neglecting his wife and “on the way to ruin and had better turn about at once. He said it was true.” Her husband, meanwhile, viewed their problems as arising out of his mother and sister-in-law’s residence at South Bend. He ejected them from his residence and arranged for new lodgings for them on the other side of town instead of listening to his wife and Rev Hickman.

In 1886 Pettit obtained, through Hickman, a post with the Indiana Methodist Episcopal church, and the couple moved to West Liberty, Indiana. From this point on, Hattie Pettit became a preacher’s wife. “She was devotedly attached to her home, her daughter…and her husband.” All accounts show that she was very popular with her husband’s congregants, in fact far more popular with them than he ever was. In 1888 the two moved to Shawnee Mound in the south-west corner of Tippecanoe County, to a church with many wealthy farming families. “She was admired and loved by all who came into contact with her at Shawnee Mound,” but very unhappy in her marriage. Her husband’s carousing in Masonic circles, if anything, was only worse and the couple were chronically short of money. Additionally, he was showing interest in other women and was “pinching the sisters of the church.” She continued to seek counsel from her old pastor, the Rev Hickman, who passed by on occasion. Hickman again pleaded with Pettit to change his behavior, even breaking down emotionally in the process. This time Pettit merely laughed him off.

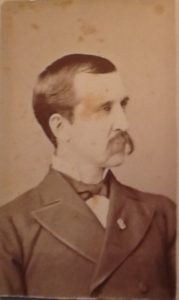

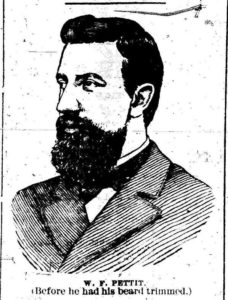

The Rev William F Pettit

Although William Pettit was convicted of murder and died in prison, his actions truly shocked most of his associates. Having left a very shady background behind him in New York, Pettit used his move to Indiana to join the Freemasons and to remake his image as a true pillar of the community. In social circles he presented the image of an intelligent and successful young up and comer. He was said to possess “a suave, polished manner, an attractive address… and was possessed of an unusual energy and progressiveness.” If he cultivated an upstanding public persona to the rest of Indiana, in his private moments he demonstrated a selfish, callous and mercenary approach to life. Pettit, one reporter noted, “has a fine presence and a personality that makes itself felt to the approaching stranger, betraying, at times, feline, sly and retreating characteristics that afford a key to his character.”

Although William Pettit was convicted of murder and died in prison, his actions truly shocked most of his associates. Having left a very shady background behind him in New York, Pettit used his move to Indiana to join the Freemasons and to remake his image as a true pillar of the community. In social circles he presented the image of an intelligent and successful young up and comer. He was said to possess “a suave, polished manner, an attractive address… and was possessed of an unusual energy and progressiveness.” If he cultivated an upstanding public persona to the rest of Indiana, in his private moments he demonstrated a selfish, callous and mercenary approach to life. Pettit, one reporter noted, “has a fine presence and a personality that makes itself felt to the approaching stranger, betraying, at times, feline, sly and retreating characteristics that afford a key to his character.”

William F Pettit grew up in Mexico, NY, roughly twenty miles from his wife’s hometown. His father was a wallpaper hanger, but treated his son very poorly. Cold and distant, he beat his son mercilessly as a child whenever he cried. The young Pettit attended Mexico Academy, grew to be a strapping six feet tall, and after graduation hung wallpaper with his father. In the late 1870s he began to get into trouble. He seems to have become involved with some unsavory friends, and ended up being sentenced to several months in the county jail for stealing a revolver. There are intimations that he was involved in other criminal activities at this time, as Pettit worked hard in 1889 to prevent investigations into this past conduct, telling one acquaintance that “his back life was too bad to try to clear it up.” During this time it would appear that he was deeply in love with a woman in this criminal milieu, but his father refused to sanction the marriage.

Pettit claimed to have turned his life around after getting out of jail. After qualifying as a schoolteacher, he became a fervent Methodist, soon after which he began using his profound oratorical talents as an unordained revival preacher. During this time he met an older schoolteacher, Hattie Sperry, at both work and at church. According to one source from New York, he did not love Sperry, but she reminded him in certain ways of his first love, and married her out of “spite” towards his father.

After the two got married and resettled in Indiana, Pettit dropped school teaching and went to work as a collector for Studebaker. Since his criminal background in New York was unknown, Pettit was able to become a Freemason by shielding his felonious past. Freemasonry quickly developed into Pettit’s favorite activity and he clearly enjoyed the pageantry and male fellowship that it involved. He also demonstrated an ability to impress older, influential men and rose quickly through the various ranks of the Scottish Rite and the Knights Templars. He soon became known as “a man of wonderful fascination and strength of purpose.” An admiring fellow Mason said that Pettit was:

a man of commanding stature, possessed a deep and sonorous voice and could be extremely genial when he pleased to do so. He had an easy flow of language and gained some popularity as an orator. He made friends rapidly….Pettit devoted much of time outside of the pulpit to masonry….he was an active member of the order and was always a welcome guest at banquets held by the order.

Pettit’s goal was to obtain both the 32nd Rank in the Masons and the Grand Prelate office in the Templars, both of which he achieved in early 1889. These Masonic activities also facilitated his move into the Methodist church, since the typical Midwestern Methodist minister of this period was a member. Thus, fellow Freemasons George W. Switzer and William Howard Hickman were presiding elders in the Northwest Indiana Methodist Conference. Through such connections, Pettit received his ordination in 1886 and obtained a post in West Liberty, Indiana. These connections were crucial, because Pettit did not seek ordination out of sincere religious conviction. Rather, he became a preacher “from a business standpoint.”

Because his heart was not fully in it, Pettit was not a particularly successful preacher. In his first appointment, there was “always more or less dissatisfaction among his congregation.” As the Methodists commonly rotated their ministers, Pettit soon found himself in Shawnee Mound in early 1888, his friend Switzer’s most recent appointment, described as “a rather select congregation.” “The church is one of the finest suburban places for worship in the State, and the congregation has a wealth that would support the leading church of a city,” wrote one observer. In an auspicious start, Pettit “advanced new ideas, worked with undaunted vim, and soon became recognized not only as a preacher, but a leader.” After this impressive start, Pettit fell out with many of his flock in late 1888. Many members of his church wanted to erect an amusement and social hall on the site of an abandoned school building, and Pettit encouraged the group to form a corporation—even going as far as writing its legal documents himself. When the group opted to place the building on private land belonging to the Meharry family, Pettit went into a rage at a public meeting, tore up the documents he had drafted, and refused to have anything further to do with the matter. “The controversy divided his congregation,” and before long Pettit began replacing his opponents with positions in his church with his supporters. Until he resigned his position in late 1889, Pettit had many [prying] enemies in his congregation—many of whom would provide damning testimony at his trial.

Despite these problems internal to Shawnee Mound, Pettit was becoming increasingly prominent. In 1888 he was elected as the Secretary of Battle Ground Camp Meeting Association, an annual two-week revival run by the Northwest District Methodists that attracted more than five thousand visitors a year. In the same year he was elected Grand Prelate of the Indiana Knights Templars, making him one of the highest-ranking members of that Masonic organization. He also achieved his 32nd Degree in the Scottish Rite in early 1889. In the months prior to his wife’s murder he continued to maintain these positions of social prominence. At the Knight’s Templar’s annual St. John’s festivities, held in Shelbyville in June, he gave the keynote address to the assembled dignitaries, and was joined as the dais by none other than William Hacker, “the founder of Indiana Masonry.”

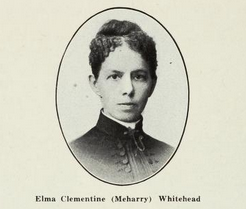

Clemmie Whitehead

Elma Clementine Meharry Whitehead, tall and skinny with an upturned nose, was not a particularly good-looking woman. As one newspaper hack put it, “the most liberal of men would hesitate to call her attractive.” Despite her undoubted plainness, her status as the wealthiest widow in western Indiana brought her several suitors of a dubious nature. She was the daughter and heir of David Meharry, who had ventured into Indiana in the late 1820s with his six brothers and begun purchasing land in Montgomery and Tippecanoe Counties. He quickly acquired 640 acres in Jackson Township, and remained there until his death sixty years later. David Meharry not only had donated the land on which the Shawnee Mound church was built, but he had also paid for the building of the parsonage in which the Pettit’s lived. If his brothers had far outshone him in terms of acreage owned and philanthropic donations made, he was still of considerable means. The seven brothers had all been devout Methodists, and had been founding members of the Shawnee Mound church, formed at the time of their arrival in Indiana. Such was the wealth and farming acumen of the Meharrys, all of them fervent abolitionists, that he and his brothers provided the endowment for the Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee, a Methodist-affiliated institution that was the South’s first medical college for freedmen. Pettit, who had helped write her father’s will in early 1888, understood that Clemmie stood to inherit much of her father’s estate—which was valued at $40,000. She also had other assets of some $8,000, inherited from her late husband, a Civil War veteran and Methodist minister many years her senior who she had been married off to as a twenty-one year old in 1871.

Elma Clementine Meharry Whitehead, tall and skinny with an upturned nose, was not a particularly good-looking woman. As one newspaper hack put it, “the most liberal of men would hesitate to call her attractive.” Despite her undoubted plainness, her status as the wealthiest widow in western Indiana brought her several suitors of a dubious nature. She was the daughter and heir of David Meharry, who had ventured into Indiana in the late 1820s with his six brothers and begun purchasing land in Montgomery and Tippecanoe Counties. He quickly acquired 640 acres in Jackson Township, and remained there until his death sixty years later. David Meharry not only had donated the land on which the Shawnee Mound church was built, but he had also paid for the building of the parsonage in which the Pettit’s lived. If his brothers had far outshone him in terms of acreage owned and philanthropic donations made, he was still of considerable means. The seven brothers had all been devout Methodists, and had been founding members of the Shawnee Mound church, formed at the time of their arrival in Indiana. Such was the wealth and farming acumen of the Meharrys, all of them fervent abolitionists, that he and his brothers provided the endowment for the Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee, a Methodist-affiliated institution that was the South’s first medical college for freedmen. Pettit, who had helped write her father’s will in early 1888, understood that Clemmie stood to inherit much of her father’s estate—which was valued at $40,000. She also had other assets of some $8,000, inherited from her late husband, a Civil War veteran and Methodist minister many years her senior who she had been married off to as a twenty-one year old in 1871.

After being widowed in 1876, she moved home from central Illinois and lived on her aging widower father’s opulent farmstead in Shawnee Mound, Tippecanoe County. With the aid of servants, she looked after her father and took care of many of his postmaster duties as well as her mentally disabled adult brother. By all accounts she was a devoted member of the Shawnee Mound Methodist Church, an excellent organist and the director of its choir. Additionally, she poured considerable time into local affairs. “She was the acknowledged social leader of that prosperous community, and she was also the most influential woman in that strong church.”

If Clemmie Whitehead was a respectable widow and a member of a wealthy and upstanding family, she was far from a virtuous woman in her private life. Elements of the sordid seem to have soiled her background. Her father was the longstanding postmaster for the township, a side business that he ran out of his homestead. Following the death of her husband, she returned to Shawnee Mound and ran the post office for her father. Some instances of mail tampering, though, led to postal investigations and censure. She continued, however, to be the de facto postmaster. Mrs Whitehead was also not shy about seeking out male company. During the 1880s she socialized regularly in Lafayette and began an affair with Septimus Vater, the gallant [and married] publisher and editor of several Lafayette newspapers. Vater seems to have been well known amongst his fellow Masons for stealing into the Black neighborhoods of Lafayette in the wee hours to frequent women of the night, and did not have a particularly upstanding reputation. In addition to visiting Mrs Whitehead regularly and embarking on numerous unaccompanied “moonlight rides” together, the pair also went alone to Cincinnati and elsewhere. Clemmie’s family took serious exception to this adulterous relationship, and eventually reacted by threatening Vater. The latter was then “ordered to desist” and to stay away from Shawnee Mound thereafter to escape their “choler”. Apparently he chose to cut a wide berth thereafter when travelling in the area, although he and his wife did continue to entertain Whitehead at his home in Lafayette when she was in town.

The Rev George W Switzer

The Rev George Switzer is critical to the case because of his efforts to bridge the gap between popular and official justice. He was the most influential member of the North-West Indiana Conference of the Methodist church for several decades, and served as a preacher in Shawnee Mound, Crawfordsville, West Lafayette, and many other stations. He first met Pettit in 1886 when the latter was ordained, and then handed over the Shawnee Mound congregation to Pettit in late 1887. He then served as Crawfordsville Methodist preacher until 1893. Additionally, he was a member of the Lafayette and Crawfordsville Lodges, and was active as well in the Knights Templar. As a result of these activities he grew to know William Pettit intimately.

Switzer’s importance to the case is that he visited Pettit’s house on the evening of the murder and became immediately suspicious of foul play when he witnessed secretive displays of affection between Pettit and Whitehead. He heard many rumors surrounding the case from former parishioners, and also gossiped and rumor-mongered on his own account. Before long he instigated and led an investigation into Pettit on behalf of his organization. In the face of this scrutiny, Pettit resigned. With his investigation stymied as a result, Switzer pestered local law enforcement to look into the case, while simultaneously creating an informal press campaign to put pressure on the authorities. His December 1889 discussion with Whitehead in which she admitted an affair with Pettit was also crucial evidence in the case. The judge, however, refused to allow the testimony to stand.

The people of Crawfordsville applauded Switzer for his role in the case, because if not for his own considerable efforts Pettit would have never been tried. “Mr Switzer is vindicated,” noted the Crawfordsville Argus following Pettit’s conviction, “if he needed a vindication. It was not ‘a lot of neighborhood gossip and old women’s yarns.’” Meanwhile, the State Supreme Court referred to him as a “meddler”. Switzer’s role thus epitomized the tension between Indiana’s popular and official justice systems.

Switzer went on to have an illustrious career in the Lafayette area. He served as Presiding Elder for the Conference until 1909, when he became a banking executive and a DePauw University trustee. Today he is best known as one of several witnesses to a UFO-type sighting that occurred in Crawfordsville in September 1891.

The Affair

Pettit and Whitehead’s affair took around a year after his arrival in Shawnee Mound to get underway. The two lovers, though, seemed oblivious to the fact that their liaison was noticed almost immediately. Even before the murder, Whitehead was being referred to by local gossips as Pettit’s “Second Wife.” Was it a pure love match? For her, it undoubtedly was. And while there are grounds for believing that his motives were purely mercenary, he seems to have truly enjoyed her company. Whatever the nature of their love affair was, both were undoubtedly people whose true character was masked. Despite a strong façade of religiosity and high social standing, both were devious, cunning, and morally ambivalent individuals who admired the qualities they saw in each other.

As neighbors in Shawnee Mound, the two seem to have first moved beyond casual acquaintance early in 1888, when Clemmie’s aging father asked for Pettit’s help in revising and witnessing his will. Meharry had two adult daughters, while his only son was mentally disabled and was judged incompetent to receive an inheritance. Pettit’s excellent “penmanship” led him to play a major role in preparing this document, most notably his suggestion to divide up Meharry’s farmlands slightly differently so that Clemmie would become heir to a larger share of his property. Later court testimony, though, is quite insistent that Pettit barely knew Clemmie at this time, and this intervention to add to her share of the estate was purely objective in nature. What Pettit’s involvement with the Meharry will undoubtedly resulted in, though, was his awareness that she stood to inherit some $20,000. There is no doubt that he remembered the exact amount.

Initially, though, Pettit does not seem to have paid particular attention to Whitehead—even though in later times it was believed that he immediately began scheming to win her heart after drawing up the Meharry will. Instead, during his frequent visits to the Meharrys the first target of his affections was Ollie Reese, the Meharry’s live-in maid. Throughout early 1888 Pettit gave Reese unwanted sexual attention regularly, pinching her derriere and throwing his arms around her on multiple occasions. When these advances went nowhere, he seems to have set his sights on Whitehead, a widow eight years his senior. Pettit described Whitehead as “sickly and homely” to some, “superior to his own wife” to others, and as a “real snug widow” to drinking companions.

By late 1888 Pettit had alienated many in his congregation in the aforementioned recreation hall fiasco and probably had no idea that he was being watched carefully as his affair with Clemmie Whitehead began. They were first noticed together alone when they attended a revival together in another part of Jackson Township. These excursions continued throughout the winter, as they went by buggy unaccompanied to other functions in nearby towns such as Odell and Wingate, where they were observed to be “looking at each other lovingly” before returning late at night. At other times they were seen “talking, laughing, eating, and walking together.” Around this time Mrs Pettit asked Reverend Hickman again to intervene on her behalf. Not only was her husband suspected of dalliances, but he was clearly neglecting his family and his duties by also spending too much time on Freemasonry and drinking. This intervention went nowhere, leaving Hickman to despair of any positive ending to the story. Pettit denied any wrongdoing, admitted to being with Whitehead a lot, but “felt free with her as she was a preacher’s widow.”

The Pettit-Whitehead affair only picked up further steam in the summer. When Pettit traveled by train to attend a Grand Lodge meeting in Indianapolis, Whitehead joined him, and they were spotted together. When Mrs Pettit took a month’s long sojourn to see an old friend in South Bend in June, Pettit and Whitehead were inseparable. This month appears to be when they both first consummated their relationship and hatched the plan to murder Mrs Pettit. Pettit lodged with the Meharrys almost the entire month of June, sleeping in a room directly across the hall from Whitehead. The two seem to have continued a pattern of indiscretion, seemingly unaware that their behavior was being monitored. The maid heard them having sex late at night, while others witnessed moments of affection in other parts of the house. Pettit had considerable work and correspondence to complete regarding the upcoming Battle Ground conference, and did all this work in the room that functioned as the Jackson Township postal office—where Whitehead took care of his mail. When the two sought to be completely alone during the day, they ventured out separately and met at locations different from where they told others that they were heading to.

During Mrs Pettit’s absence in June the murder conspiracy was hatched—if one is to accept the Rev George Switzer’s disallowed testimony regarding the “confession” Clemmie Whitehead later gave him. At some point Pettit told Whitehead “that he loved her and disliked his wife,” and that he wanted to marry her. They began having sexual relations. She also agreed that in the future she would marry Pettit, but “Hattie was a dear friend of hers and nothing must happen to her.” This statement denying her own culpability in seeking to injure Mrs Pettit does not ring true given that she took the fifth in order not to testify in front of a grand jury. Nor does it square with the fact that she admitted that she and Pettit “congratulated each other when the first grand jury failed to act” following Hattie’s death.

The murder plot was thus hatched by late June 1889, shortly before Hattie Pettit’s return from South Bend. On July 1 Pettit went to a nearby merchant’s store, asking in a sotto voce manner to purchase strychnine. When the merchant said he had none on hand, and was also reluctant to order any from him, Pettit unsuccessfully asked him to reconsider. This setback was not an insurmountable problem for Pettit, because he had already purchased a tin of strychnine in the summer of 1888 when the parsonage had been afflicted by a rodent problem. It is possible that much of this original batch had been used and Pettit was unsure if he had enough to kill his wife. Alternatively, he may have felt the old batch may have gone stale and would not work. A couple of days later Pettit put out some strychnine around the parsonage, leading to the death of his daughter’s beloved dog. State prosecutors interpreted this event, probably correctly, in Pettit assessing how potent the year-old batch was and whether it could kill a human.

The Murder

Rev Pettit wasted no time at all in executing his plan following his wife’s return. Hattie returned on the evening of Friday the 12th, and was dead within five days. Although there were no witnesses who could testify to seeing Pettit administer strychnine to his wife, there was significant circumstantial evidence to that effect. During the four days in which Mrs Pettit fought for her life she was poisoned on at least three occasions. Nobody other than Pettit or Whitehead fed her during this time, and witnesses remembered the two feeding Mrs Pettit shortly before each set of strychnine convulsions began. Moreover, Pettit and Whitehead’s behavior during Mrs Pettit’s convulsions continued to be intimate, with the two being spotted alone together several times. They were also heard having sex furtively on the night before the murder, and on the day of it as well.

Pettit spent Saturday with his wife and daughter, dealing rudely with various callers who came to see her after her absence and ensuring that they did not stay the night. Hattie then got sick overnight for the first time, although it appears that the first strychnine dose she received was far too small to be fatal. After having stomach pains all night, she was able to attend church the next day. Pettit had to preach to a nearby congregation, where he cut short the sermon in order to return home to attend to his ailing wife. On returning home, he called for a close friend, church member, and fellow Freemason, Dr John Yeager, to come and attend his wife. Hattie told Yeager that she believed that she had been poisoned by strychnine, which she believed that she had ingested while cleaning the cupboards the previous day. Pettit, meanwhile, downplayed this explanation, and sought to convince Yeager that his wife had contracted malaria in the swampy environs of South Bend.

Doctor Yeager’s treatment of Mrs Pettit undoubtedly assisted the murder to take place. He had never before assisted in a poisoning case. By his own admission, his close relationship with Pettit affected his judgment—he feared Hattie was being poisoned but was unwilling to draw that conclusion. Hence, he treated her for poisoning while in public maintaining that she was suffering from malaria. He was to continue with this dubious malaria verdict even after her death “in order to hush gossip”. “I earnestly desired that something might in the Providence of God transpire that would satisfy my mind that Hattie Pettit died of something else than strychnine.”

Clemmie Whitehead arrived at the parsonage to help care for Mrs Pettit shortly after Yeager’s arrival on Sunday. She would not leave until the day after the murder. On the first day she helped administer emetics to Hattie, following which the latter’s convulsions stopped and she felt far better. Thereafter, she acted as Hattie’s nurse throughout the entire episode, remaining at her bedside for long periods. Hattie, meanwhile, suspected nothing throughout, at one point telling Whitehead “Don’t go away. I want to know you are in the house.”

Monday was a day of recovery for Hattie. Yeager visited twice, prescribed emetics, and found her improved several times. He believed her recovery to be imminent. The only other noteworthy event that day occurred when Pettit and Whitehead stole into the hallway. While they were alone together, they somehow managed to break a window, and raised some eyebrows with their non-explanation of the event. It would appear, though, that in their time together they decided to renew their efforts with increased dosages of strychnine.

Pettit clearly poisoned his wife early the next morning, leading to a turbulent Tuesday for all involved. At dawn he gave his wife capsules of quinine that he had prepared on the advice of Yeager. Not long after she began convulsing, Yeager arrived. He maintained in court that she must have been poisoned shortly prior to his seeing her. Mrs Pettit was in agony, fearful of death, and was prescribed chloroform and morphine for relaxation. Pettit and Whitehead remained at her bedside the entire day while she slept. Yeager returned in the evening, stayed for some time, while Whitehead continued to act as nurse. The medication mitigated the symptoms, but Mrs Pettit was in very poor condition. During the late hours, Pettit and Whitehead continued to be indiscreet. He visited her room alone around midnight. In the morning, when she bathed, she was alone again together with him upstairs in the parsonage, following which the two came down to breakfast together.

Events moved swiftly on Wednesday the 17th. A second physician, Dr Black, who had been called on Tuesday, arrived after breakfast. After seeing the patient and consulting with Yeager, he confirmed a diagnosis of malaria. Black told Yeager and Pettit that the patient would not recover, and left soon after. This diagnosis seems to have triggered Pettit’s determination to act decisively. At eleven, he gave his wife “a powder which Pettit prepared after the consultation” with Yeager. He “insisted on giving his wife her medicine, passing into an adjoining room to administer it.” This renewed intervention triggered another set of violent convulsions once it was ingested. At around noon, with his wife suffering terribly, Pettit also gave her some oil from a cup. Half an hour later she was dead. “Mrs Pettit died in very hard convulsion with arms drawn up, body curved to right, toes turned down, and body rigid….Expression on face after death showed great agony….after death Pettit threw himself on the bed beside the body and said ‘O Hattie, you have done so much for me, but what have I done for you.’”

The deed was done.

Pettit then acted very quickly to arrange a funeral. Within hours, after a flurry of telegrams, he arranged for a prayer service that night, a funeral at Shawnee Mound early the next morning, and summoned the Revs Switzer and Hickman and to officiate at them. A funeral parlor in Lafayette was instructed to “send man with full tools by fast team to thoroughly embalm” his wife immediately following the funeral, and after the embalming her body was to be transported by train to her home town in New York where a funeral and burial would be held.

The next day news of her death was publicized in the Lafayette Daily Journal, and the official cause of death recorded as malarial poisoning.

The Popular Justice Campaign Against Pettit

There are many rumors concerning the death of Mrs Pettit afloat, new ones seeming to grow out of every hour that passes.

During the four months following Mrs Pettit’s death, a growing campaign for an official investigation into her death took place. On the one hand, this unofficial campaign involved many Shawnee Mound residents who used rumor, gossip, and shaming to create a groundswell of opinion. On the other, the Reverend Switzer was able to use his contacts to generate regional press publicity and to meet with officials. The combination of these forces eventually led authorities in Tippecanoe County to open an investigation and order an exhumation of Mrs Pettit late in the year.

The “unofficial” rumor and gossip campaign cannot always be traced chronologically. It followed directly from public disapproval of the Pettit-Whitehead affair, and was rampant as early as the very afternoon of the murder. By the evening of the murder Switzer and Hickman became the focal points of the gossip campaign when they arrived to perform funereal services for Mrs Pettit. Both were Freemasons and both knew Pettit well.

Switzer and Hickman suspected murder even before arrival at the Shawnee Mound parsonage on the 17th, and became convinced of it that night. Hickman told Switzer about Mrs Pettit’s confidences to him on the way, and both men “did not think all was right there” on arrival. Switzer, meanwhile, had heard disturbing reports about Pettit from his former congregants, testifying that, “Pettit’s conduct with Mrs. Whitehead had been noticed months before his wife’s death.” Both he and Hickman were on the alert for foul play. When Switzer got to his former residence and went upstairs to see the widower, he found Pettit and Whitehead cuddled up together on the sofa. He also found them alone together an hour later. After these incidents Switzer apparently determined to stay awake all night and to keep an eye on the two. He saw the two go outside alone together, and then the two had a long conversation after entering the house. Having a fitful sleep, he was later awakened around 3am and heard the two having sex in her room. The following day, Pettit’s swift actions in respect to his wife’s burial further aroused Switzer’s suspicions. The funeral was held at 7am, following which the body was hastily embalmed, and then driven quickly by buggy to be put on the train at West Point by 11am. Pettit then escorted the body for burial in Oswego, New York.

Following the departure of Pettit the rumor mill began in Shawnee Mound. The servant Ollie Reese made it known that her mistress, Mrs. Whitehead, had confessed her affair with Pettit to her one day in private. Meanwhile, details regarding the attempted strychnine purchase at Odell, the death of the Pettit dog, and Pettit and Whitehead meeting in Lafayette after he got back from the funeral in New York, also got tongues wagging. Soon after, the pair attended the Old Settler’s Picnic at Meharry Grove near Shawnee Mound, an annual event that attracted the oldest families in the area. At this point, the shaming of Pettit began. When Switzer saw the two together at the picnic, he admonished Pettit openly. When the latter asked Switzer what the public sentiment was regarding him, Switzer told him it was “very bad.” At the same meeting the Meharry lawyer also confronted Pettit about “making love” to Whitehead, although he denied having done so prior to his wife’s death. Soon after this, members of the Shawnee Mound congregation decided to hold a church meeting to discuss the allegations with him. At this meeting some openly condemned him for his actions. Pettit admitted to being “indiscreet” with Whitehead, but denied having an affair or having fomented any other wrongdoing. Many members of the congregation believed him and supported him. In the aftermath of this meeting, Clemmie’s father David Meharry, changed his will and apparently wrote her out of it. According to Meharry’s testimony, he did this because “he had observed the connection” between them, and had heard “so much talk about Pettit and Mrs Whitehead in the country.” Soon after, he also confided to Switzer that “a terrible calamity” was occurring in his family due to the affair.

Given Pettit’s obduracy at admitting anything resembling guilt, a letter-writing campaign began. Pettit himself received an anonymous ”threatening” letter, while his sister-in-law Laura Shields also received a letter that encouraged her to believe that her sister had been murdered, that “suspicion points to one who hides a wicked heart under a cloak of religion.” She in turn wrote to Andrew McCorkle (who had accompanied the body to New York) asking for more information about the case, requesting in particular that Doctor Yeager provide more details about Hattie’s death. McCorkle, himself no stranger to the rumor mill, confronted Yeager and the latter all but admitted that strychnine poisoning was the cause of death and not malaria. He had merely inserted malaria as the cause of death “as he would rather be mistaken on the side of humanity and mercy than be mistaken otherwise.” Pettit, meanwhile, delayed for over a month in providing his sister-in-law an explanation of Hattie’s death. Ultimately, Shields would accept his explanation while coming to believe that Whitehead was the murderer.

All this was simmering when the annual Battle Ground conference was held. This was an annual event held by the North-West district of the Indiana Methodist church north of Lafayette. For the four nights prior to the Conference, Pettit stayed at the Meharry’s and as usual slept across the hall from Whitehead. They were overheard sleeping together one of these nights in her bedroom. A storm, though, was brewing. On August 30th, an article appeared in the Crawfordsville Press describing “a scandal of high dimensions which gives promise of still further developments.” This article, which was instigated by Switzer through a journalist friend, made reference to many matters—the suspicion of strychnine poisoning, the anonymous letters, the open liaison that had developed between Pettit and Whitehead since his return from New York, and other “stories that had developed and traveled fast.” The article featured a short interview with Pettit, who “said that the stories were a lot of lies concocted by enemies of his in order to injure him.” The following day a similar story appeared in the Cincinnati press, following which it became a minor Midwest sensation.

The Battle Ground conference, meanwhile, was looming as a potential source of drama. All Methodist ministers were expected to conform to high ethical and moral standards, and “complaints” could be made against them for poor behavior. Prior to the conference, Switzer made an oral “complaint” against Pettit to the Methodist bishop, who then referred the matter to the North-West District cabinet (“a secret body consisting of bishop and presiding elders”) for review. Pettit was informed of the charges and the fact that he faced an internal investigation.

Pettit travelled alone to the conference, and on the train to Lafayette encountered the Rev. S. P. Colvin. Being the longest-serving member of the conference, Colvin had been involved in some twenty “complaints”, and Pettit asked him to represent him. Their conversation, which represents the closest thing Pettit ever came to making a confession, was never retained in confidence as Pettit assumed it would. According to Colvin, Pettit admitted having an affair with Whitehead, to murdering his wife, and to frequenting saloons to smoke, drink, and play cards—all offenses worthy of his expulsion. He only denied having acted improperly in helping David Meharry draw up his will. “I told Pettit his case was indefensible….I advised him to withdraw from ministry and church and get out of the country.” This was the best advice William F Pettit ever received, but he neglected to listen to it.

Having been told to flee the United States and having been the subject of scandalous gossip and newspaper stories, one would have thought Pettit would adopt a circumspect attitude at the Conference. His wife’s death was by all accounts the main topic of conversation at the event! Unfortunately he was remarkably indiscreet. Regular attendees at the annual event had purchased cabins on site, and David Meharry was no exception. Although he did not attend, his cabin was used by some in-laws, the Hawthornes, as well as by Whitehead and Pettit. This was a volatile situation, since several of the Hawthornes had publicly attacked Pettit, while the latter believed them to have been behind accusatory anonymous letters. Whitehead and Pettit were together a lot of the time, and tried to avoid their housemates the Hawthornes as much as possible. The Hawthornes, however, saw the couple “caressing” and displaying affection, heard the couple making love late one night downstairs, and also discovered over the weekend that the two planned to get married in the near future. This plan they objected to strenuously.

While these dalliances were occurring, a minor war erupted in the newspapers over the virtue of Whitehead and Pettit. Septimus Vater, the editor of the Lafayette Call, defended the honor of his former lover Whitehead, and maintained that his friend Pettit was innocent of all the rumored charges being made against him. Unfortunately for Vater, rival newspapermen in Crawfordsville responded by not only exposing his affair with Whitehead, but by revealing his penchant for late night whoring in the Negro section of Lafayette. Given the late-night carousing that often followed lodge meetings, combined with the fact that Pettit usually stayed with Vater while in Lafayette, the denunciations implicated Pettit in similar behavior (which he did not deny to Colvin).

As the investigation proceeded at the Battle Grounds, Pettit tried to persuade several fellow Masons in “the cabinet” to end the investigation. This failed. On the third day of the conference he was brought before it, where he was instructed to resign. Pettit maintained his innocence in front of the group, claiming that an investigation would clear him. After being instructed again to withdraw, he agreed, then fell down on a bed, and cried like a baby. He was no longer a member of the Methodist Church. The following day he returned to Lafayette, where he was interviewed. Once again he maintained his complete innocence, while also claiming that his close friendship with Whitehead had been “misconstrued”.

In order to escape the extreme social pressure that they faced, both Pettit and Whitehead vacated Shawnee Mound. Pettit moved to the Battle Ground campsite, where he retained his paid position, while Whitehead went to stay with one of her sisters in Ohio. The two then corresponded daily and began to make plans for their wedding. In late September he obtained a job as a sales agent for a Methodist publisher and prepared to move to Ohio as well.

At this point the Lafayette Grand Jury looked into the case, called thirty witnesses, and declined to prosecute.

By the end of September the unofficial rumor campaign was beginning to lose steam. Gossip still ran rampant, and Shawnee Mound residents joked about Whitehead paying potential witnesses to emigrate to the Indian territories in order to silence them. News that David Meharry had rejected a proposal by Pettit to marry his daughter spread, though the old man denied that such a proposal had ever been made. The authorities were making no move to investigate the crime following the Grand Jury decision. Denied a formal investigation at the Battle Ground, Switzer, however, continued to push the matter with authorities. Switzer looked into the rushed embalming and burial of Mrs Pettit, and learned that Pettit had had his wife embalmed “using extreme means” that would make a post-mortem difficult. Not wanting to be silenced by this revelation, he had the information published. Even so, no official action occurred:

The people in Shawnee Mound which had taken an interest in the case charged openly that the prosecuting officers had not performed their duty and that Pettit was allowed to escape justice because he stood so high in the Masonic fraternity and because of Masonic influence.

While popular opinion felt around Shawnee Mound held that “Masonic influence” was hindering the application of justice, in actuality Pettit’s fellow Freemasons both helped and hindered him. The Tippecanoe prosecutor, George Haywood, was himself a high-ranking Mason and Templar, although he did not know Pettit personally. In fact the latter actually used a Masonic intermediary to try and have him intercede with Haywood. Haywood was in any case brand new in his position, and, if anything, a changing of the guard at the Tippecanoe County prosecutor’s office was probably the greatest cause of official inaction. Other prominent Freemasons in the county, such as Septimus Vater of the Lafayette Call and his counterpart at the Lafayette Daily Journal, were also highly skeptical of Pettit’s guilt at this point in time. The Masonic connection, though, cut two ways. George Switzer was also, like Haywood, a Mason, a Templar, and a Methodist, and managed to convince him in person during October to investigate the case. In November, a secretive order to exhume the body was issued and officials proceeded to New York. Once the body was taken out of the ground, the organs were removed and sent off to Chicago for analysis.

The evidence from two different laboratories showed large amounts of strychnine in Mrs Pettit’s body.

Once the evidence was in, the State of Indiana set about prosecuting Pettit and used all the resources at its disposal to do so. Haywood was in fact to make a name for himself as a lawyer, prosecutor, and politician through his efforts in the case. He sent agents to arrest Pettit in Ohio, and also informally arranged with Switzer for the latter to go and interview Whitehead privately. Switzer then ventured to Shawnee Mound and met with Dave Meharry and Clemmie Whitehead. After Switzer promised complete confidentiality in the matter, Whitehead provided him with a full timeline of their love affair, and admitted that she agreed to marry Pettit three weeks prior to his wife’s death. She claimed to know nothing regarding her poisoning, though, claiming that she had been willing to “wait” to marry Pettit. This confession, which Switzer testified to before a grand jury less than four days later, provided enough ammunition to Haywood for him to decide to prosecute both parties. It was also to prove the final intersection between popular and state justice. The rest of the case would remain in the hands of the prosecutor and the courts.

The Trials

If the preceding discussion has made Pettit’s guilt seem evident, the outcome of the year-long judicial process that would ultimately convict him was in doubt until the very end. Pettit had many private and a few public supporters, as well as an expensive and competent defense team. His detractors, convinced of his guilt, feared his connections and resources would corrupt the judicial process.

Pettit was arrested in Columbus, Ohio in early December, and brought back to Lafayette amid considerable publicity. Although he was never to regain his freedom again, Pettit presented a strong front throughout his public appearances. “His bearing is indicative of the utmost composure,” wrote one accompanying journalist. Visited by numerous Masonic colleagues and female admirers in the Indianapolis, Lafayette, and Crawfordsville jails, he occasionally would receive journalists. These interviews, though, are not revealing—rarely was anything ever said beyond a protest of innocence combined with a deep conviction that he would be vindicated in the end. Pettit was granted bail of $10,000 not long after his arrest, but was never able to raise it—in the eleven months before his conviction he was to remain in jail. Most of this was spent in Lafayette, where his case was heard before a Grand Jury in March 1890. With his defense funded by Whitehead, Pettit hired the colorful Civil War veteran Col R.P. DeHart as his lead attorney, with the latter being commonly believed to be the most able lawyer in Lafayette. DeHart was to lead a spirited and expensive defense.

In the initial Grand Jury hearing, Pettit and Whitehead were jointly indicted, and the state brought forward most of its key witnesses. During these first hearings, the defense worked hard to demonstrate that there was no murder conspiracy. Although this approach was initially unsuccessful at the Grand Jury stage, ultimately it would be successful for Whitehead. The prosecution established a strong case for habeus corpus, and also convinced the judge that the basis of a murder conspiracy existed. Pettit was then denied bail.

During the Grand Jury phase, Clemmie Whitehead’s legal experience began to diverge from her lover’s. Early in the process the Prosecution opted to delay her trial, preferring to try Pettit first rather than expose its key evidence to the defense. She was then called to testify in Pettit’s hearings and asked to produce her September 1889 correspondence with Pettit—in response she took the fifth and would never again appear in court. As her trial had been indefinitely delayed, she was given bail.

During the Grand Jury phase, the most remarkable part of the proceedings was the appearance of Dave Meharry on the stand. Now over eighty years old, Meharry had been put in a tragic situation in which his church, his post office, and his family were being brought into public disrepute. As to whether his motives were to shield his daughter from prison or to maintain the integrity of his own legacy, Meharry perjured himself repeatedly on the stand and proved an uncooperative witness for the prosecutor. Meharry painted a positive portrait of Pettit and denied he had seen anything untoward happening between the preacher and his daughter. Under assault from the prosecutor, he did admit to having rewritten his will in August because he had seen a “connection” between the two, but offered little more detail. Much of his testimony was contradicted by his younger relatives—all of whom were prominent in the early rumor-mongering in 1889.

Before Pettit’s trial began in Crawfordsville in October, Meharry took his daughter on an extended tour that reportedly included Florida and the entire West Coast. They did not return for almost two years in order to avoid being subpoenaed.

Pettit was eventually tried and convicted in Crawfordsville in the late fall. As noted earlier, the case drew large crowds daily to the courtroom as well as widespread media attention. Since Pettit did not take the stand and Whitehead was absent, most of the witnesses were residents of Shawnee Mound.

Prosecutor Haywood pursued his case in two ways. First, he relied on the testimony of the rumor-mongers who provided detailed and titillating testimony regarding the Pettit-Whitehead affair to provide circumstantial evidence of Pettit’s desire to see his wife dead. Second, he relied on the results of the autopsy to show that Hattie Pettit had been poisoned. His preview and summation of the case were effectively laid out with a great deal of energy, and he won praise for his victory in the case. The equally enthusiastic defense, meanwhile, chose not to attack the testimony of the Shawnee Mound residents. This was probably a tactical mistake. Rather, it sought to establish reasonable doubt by focusing on the inconsistent methods of Dr John Yeager during Mrs Pettit’s illnesses, as well as the lack of strychnine found in Mrs Pettit’s brain (thereby rendering doubt on whether she had been poisoned). Additionally, since only Pettit was on trial, Defense Attorney DeHart successfully suppressed all testimony brought forward that demonstrated a murder conspiracy involving Mrs Whitehead. Many observers were impressed—one local wrote, “the defense are tearing down [Pettit’s chances of condemnation quite remarkably. I don’t believe now that he will be found guilty of the charge, yet I believe he poisoned his wife.”

In retrospect, the judge’s actions during the trial are among the most baffling element of the proceedings. Judge E.C. Snyder, also a Freemason, made many rulings throughout the trial that later led the Indiana Supreme Court to demand a retrial. Some of these strange decisions included throwing out much of the Rev Switzer’s testimony, including the “confession” he obtained from Whitehead in December 1890. Additionally, when sending the jury to deliberate, he instructed the jurors that he believed a not guilty verdict was appropriate given the scientific evidence that had been presented. Both of these decisions seem highly debatable. The Crawfordsville jury, however, was unanimously convinced of Pettit’s guilt from the very start of the deliberations, and only debated after the first ballot in order to make sure that they had not overlooked some important fact. The jury also preferred a life sentence to the death penalty so that Pettit would suffer indefinitely for his actions.

The guilty verdict was perceived in Crawfordsville as a victory for popular justice. Early Pettit supporters, such as the editors of the Lafayette Call and the Lafayette Journal, applauded the verdict and maintained that justice had prevailed. As the Veedersburg News put it, “it was the universal verdict that he was guilty but no one thought he would be convicted.” The deceased’s sister maintained that her family was satisfied. The jury was feted by the townsfolk, while Rev. Switzer was greeted with rapturous applause at the next service he presided over.

In early 1891 Pettit was sent to the Michigan City penitentiary for life. Forced to perform heavy factory labor, he contracted tuberculosis and began wasting away. Even so, with the absent Whitehead continuing to pay his legal bills, he appealed his verdict all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court. He won the right to a new trial in 1893, based on both the absence of a key witness during the Crawfordsville hearings as well as some strange decisions made by Judge Snyder. Pettit, though, succumbed to his illness on the very day of this verdict. Reports vary as to whether he heard the good news prior to his death or not. His mother, in the meanwhile, had gone insane following his guilty verdict and would never recover. His daughter grew up in the care of her maternal relatives in New York, and aged into a respectable spinsterhood. Pettit’s final indignity was to have his sister-in-law refuse his burial in his wife’s cemetery plot, relegating his corpse instead to a spot next to his hated father.

Getting Away With Murder: The Fate of Clemmie Whitehead

Clemmie Whitehead was never put on trial for her role in Mrs Pettit’s death, and following the imprisonment of her lover she lived out most of the remaining eight years of life in solitude and ill health. After several years of travelling with her father on the West Coast, they returned to Indiana following Pettit’s death. After her father’s subsequent death, she spent most of the rest of her life in his house. Her most frequent companions thereafter were her close relatives who had been at the forefront of the rumor campaign.

Why was she not tried for murder? There are definitely strong circumstantial grounds for believing she helped Pettit, most notably including the fact that she had an affair with him, that she tended Mrs Pettit throughout her fatal ordeal, that she was intimate with the murderer throughout said ordeal, and that she assisted him in various ways throughout the unofficial popular justice campaign. She was also obviously an underhanded and devious person. Clearly she sought to have affairs with married men and to engage in subterfuges to avoid detection by friends and family. Additionally, in her position as a postal official she tampered with the mail on several occasions. She was the subject of a postal investigation prior to ever meeting Pettit. Additionally, she used her position to intercept, open, and remail several letters that contained accusations made against her and Pettit in August 1889. In addition to these known facts, the judge believed there to be strong prima facie evidence for a murder conspiracy, as did most observers of Pettit’s trial. “It has been given out all along that she would be re-arrested and tried if Pettit was convicted.” The state, however, decided to nolle prosequi her case in 1891.

In the absence of an explanation from the prosecution, several points appear to be germane. Perhaps most important was her father’s unwillingness to provide honest testimony or to cooperate with the prosecution in order to preserve the reputation of the Meharry family. Whitehead was also unwilling to make a confession—in her “confession” to Switzer she adamantly maintained that she had told Pettit not to hurt his wife. She claimed also to have not known that Pettit poisoned his wife until his arrest in December 1889. With Pettit not taking the stand, and with no other witnesses to contradict her, “the state realized that she could not be convicted [and] nollied the case.” Ultimately, though, it is far easier to believe that she dissimulated to Switzer than to believe that she had no idea about what was transpiring during Mrs. Pettit’s ordeal in July 1889.

In the mind of the public, it may also have seemed that Whitehead was punished sufficiently for her involvement. Her lover had been imprisoned and died, and following the death of her protective father she lived a solitary, sickly and “very sad” life. Rather than demanding a prosecution, the public rationalized her innocence and let her live out her life in quiet disgrace:

“No one ever really believed that she had any knowledge of Petitt’s intention to murder his wife. She was simply the weak victim of a strong and designing man.”

—###—

A full footnoted version of this article can be seen at: Academia.edu