Train Robbers Chris Evans and George & John Contant-Sontag,

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part II: Pacific Coast Cases

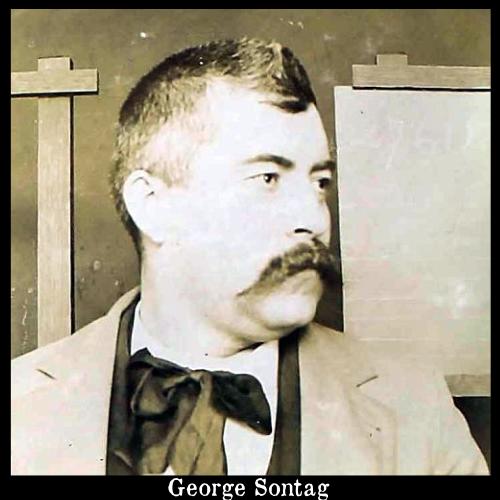

John Contant was born in Minnesota in 1861 and his brother George was born in the same State in 1864. Shortly after the birth of George, their father died and the mother married a man named Sontag, the boys taking the stepfather’s name.

They lived for some time in the town of Mankato, Minnesota, where George was employed as a train brakeman until he procured a position in a grocery store in Nebraska. While thus employed he embezzled his employer’s money and was sent to State Prison.

He had only served about a year when he escaped with a fellow convict. As they were wearing their prison garb, they burglarized a store that night and, procuring civilian clothes, they disappeared, although Sontag voluntarily returned to the prison and served out his sentence, being released in 1887.

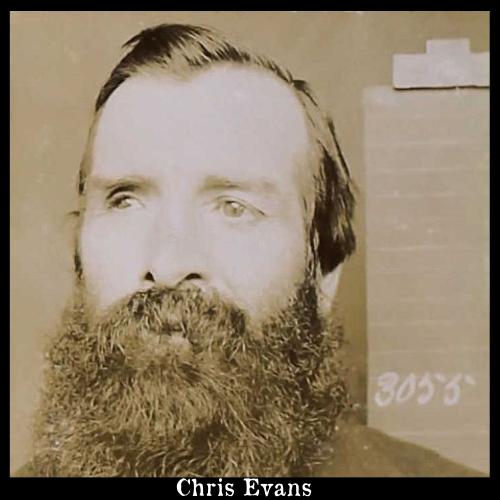

John Sontag came to Los Angeles, Cal., in 1878 and eventually became a brakeman on the Southern Pacific Railroad. He was injured while thus employed and became bitter against the company because of alleged ill-treatment accorded him after he became convalescent. About this time, he obtained employment from Chris Evans, who had a farm near Visalia, Cal.

Evans, whose long flowing beard gave him the appearance of a typical farmer, was always considered a hard-working and honest man, and his family was highly respected. He had a real or fancied grievance against the railroad company which he did not hesitate to express, and the result was that he and John Sontag decided to seek revenge and incidentally obtain a little “easy” money.

On the night of January 21, 1889, they boarded the train at a station near Goshen, Tulare County, and when they had traveled a short distance they put on masks, climbed over the tender, ordered the engineer to stop, proceeded to the express car and without any difficulty obtained about $600.00 and then escaped. They had tied a couple of horses in the neighborhood which they rode back to the ranch, returning to Visalia the next day.

On February 22 they boarded the train at Pixley, Cal., and executed another robbery in precisely the same manner as at Goshen. With the $5,000.00 obtained in this holdup they opened a livery stable at Modesto, but the stable was burned down, evidently by an incendiary.

In May, 1891, John Sontag went to Mankato, Minn., to visit his brother George, and in the course of a few days John confided to George that he had robbed a couple of trains.

In June, John started back to California and told George before he left that he and Chris Evans had planned to hold up a train at Ceres, Stanislaus County.

They attempted to rob this train and wrecked the express car with dynamite, but Detective Len Harris of the Southern Pacific Company was on the train, and he stepped out and began firing at Evans, who returned the compliment with buckshot, but no one was seriously injured. The bandits then fled to Modesto without procuring any valuables. John returned to his brother in Mankato and related what had occurred, and asked George to suggest a train that they could hold up in that neighborhood.

After studying the situation, George decided that they would hold up train No. 3, which left Chicago at nighttime and stopped at a station called Western Union Junction. They sent their relatives to Racine, Wis., and then went to Western Union Junction and waited for No. 3 on the night of November 5, 1891.

When the train stopped they secreted themselves near the tender and when they had traveled a few miles they climbed over the tender, thrust pistols in the faces of the engineer and fireman, ordered the train stopped and compelled the engineer and fireman to accompany them to the express car.

They obtained $9,800.00 without any difficulty and returned to their relatives at Racine.

It was then agreed that George should go to Visalia and meet Chris Evans, and that John Sontag would follow. When George arrived, he found Chris Evans sitting as one of “twelve good men and true” in judgment in the case of some petty offender. When he beheld Evans in the jury box wearing a sanctimonious expression and long flowing whiskers, he experienced some difficulty in keeping a straight face.

He left the courtroom and went to Evans’ home. When the latter arrived at the lunch hour they had a heart-to-heart talk regarding further “enterprises,” and George loaned Evans $200.00. As George Sontag became ill, he returned to his eastern home on April 24, 1892, before anything could be accomplished. John Sontag had returned to California in the meantime and he wrote to George to ascertain if he knew of any other good opportunity in their line back east.

George arranged to hold up No. 1 from Omaha at a station called Kasota Junction, and Chris Evans went east to participate in the job, which they attempted to execute on the night of July 1, 1892. Although George Sontag gained access to the express car, he could not locate the money and they profited nothing by the venture.

John Sontag remained in California and George wrote to him that he would proceed at once to Fresno, Cal., and that Evans would follow.

The Sontag brothers and Evans assembled at Fresno on August 1, 1892, where it was agreed they should hold up passenger train No. 17, bound from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and that the train should be boarded at Collis, near Fresno. August 3 was the night selected, and according to agreement, Evans walked out on the country road, where George and John Sontag overtook him in a buggy and Evans rode with them to Collis. When the train stopped, Evans and George Sontag boarded it, concealing themselves near the locomotive, and as usual, adjusted their masks.

As the train got under way, they climbed over the tender and ordered the engineer to stop. John Sontag did not board the train but took the team to a spot agreed upon and there awaited the other two. George Sontag marched the fireman and engineer back to the express car at the point of a gun, and when they arrived there Evans blew the door in with dynamite. The Wells-Fargo messenger threw up his hands, and George Sontag entered the car and seized three sacks of money and ordered the fireman to carry one and the messenger the other two. They started toward the locomotive which Evans crippled with a dynamite cartridge. After taking the two prisoners a short distance up the track, they ordered them to hand over the money and go back to the train. The two bandits then proceeded to the spot where John Sontag was waiting with the buggy. They drove George to the suburbs of Fresno and he went to the depot, where he purchased a ticket for Visalia, taking the same train which he had held up, as it was delayed in making repairs to the locomotive disabled by Evans’ dynamite cartridge. While on the trip he eagerly listened to the passengers who described their experience during the holdup.

John and Evans returned to Visalia in the buggy and immediately proceeded to their barn, where they opened the sacks and learned to their sorrow that they had only seized $500.00 in American money, the remainder being Mexican and Peruvian coin.

George Sontag’s actions while in Fresno planning this last robbery aroused suspicion and the team which they used was recognized as one belonging to J. Sontag and Evans. It was suspected that George Sontag knew more about this crime than he cared to tell, although the evidence against him was by no means conclusive. Accordingly, Deputy Sheriff Witty and Detective George Smith called at Chris Evans’ house and stated to George Sontag that they heard he was a passenger on the train at the time of the holdup, and that they would be pleased to interview him at the Sheriff’s office.

After interrogating him at length, Sontag was detained by the Sheriff and Witty and Smith returned to Evans’ house in a buggy. As they approached they saw John Sontag enter the house, and when they arrived they told Evans’ daughter that they wished to speak to John. The child, evidently acting under instructions, stated that he was not in, whereupon the two officials stepped inside and, seeing Chris Evans, asked him regarding Sontag’s whereabouts. He also said John was not in.

One of the officers then pushed a portiere aside and there stood John Sontag with a shotgun in his hand. The officers reached for their revolvers, but at that instant Evans also produced a shotgun. The officers, seeing that they were taken at a disadvantage, turned and ran. Evans pursued Witty and shot him, inflicting a serious wound, and when Witty fell, Evans came up to him and held his pistol at the head of the prostrate man, but did not fire as Witty appealed to him not to shoot again as he was dying. Sontag fired at Smith but the bullet missed its mark.

Evans and Sontag then went into the house and after obtaining a supply of ammunition, took the officers’ buggy and escaped. They evidently returned to the Evans’ home during the night, and on the next day, August 5, 1892, a posse consisting of Oscar Beaver, Charles Hall, W. H. Fox and Mr. Overall surrounded the house, at 1:30 p. m. Beaver saw the bandits take the horse and buggy out of the stable and he commanded “halt.” Each side opened fire; Beaver was completely riddled with buckshot and died instantly.

Sheriff Cunningham and a posse heard the shots from town and hurried to the scene, but the bandits had escaped.

Nothing further of importance occurred until September 13. On this date a posse consisting of two Indian trailers imported from Arizona, Vic. Wilson of El Paso, Texas, Al. Witty, the brother of George Witty, who was the first man wounded by the outlaws, Detective Smith, Constable Warren Hill and Y. McGinnis of Modesto, drove up to Young’s cabin, but had no idea that the bandits were in the house, although they knew they were in the vicinity. When they reached the gate, Evans and Sontag opened fire. Wilson and McGinnis fell dead and Witty fell from a shot in the neck; Hill’s horse was shot dead and the bandits again escaped.

On October 25, 1892, George Sontag was placed on trial for the Collis train robbery, and on October 29 the case was submitted to the jury, which returned a verdict of guilty after deliberating one and one-half hours. On November 3 he was sentenced to life imprisonment at Folsom.

A period of several months elapsed without anything being accomplished toward the capture of Evans and John Sontag. It was evident that they were receiving food and shelter from sympathizers in the mountains, and a great many people in the valley, who were antagonistic to the railroad and believed that there was some justification in the actions of these desperadoes. They made frequent visits to Evans’ home in Visalia and often remained there over night.

On June 11, 1893, a posse consisting of United States Marshal Gard, Deputy Sheriff Rapelje of Fresno, Tom Burns and Fred Jackson were stopping in a vacant house when they observed Evans and Sontag come down a hill and pass to the rear of this house. Evans saw Rapelje and opened fire at him. Jackson then fired, wounding Sontag and Evans. Both bandits got behind a straw stack and in some unaccountable manner they again escaped, although Sontag was wounded unto death.

The next day, E. H. Perkins, who lived nineteen miles northeast of Visalia, called at the Visalia jail and informed the officials that John Sontag was lying helplessly wounded near a straw stack in the neighborhood of Perkins’ home. When the officials learned of Sontag’s condition, and having in mind the reward, there was a wild race to “capture” the prostrate man, and he was taken without a struggle.

On the following day, June 13, Sheriff William Hall and Deputies Al. Witty and Joe Carroll placed Chris Evans under arrest at Perkins’ home. He virtually surrendered, as he was worn out and weak from the loss of blood.

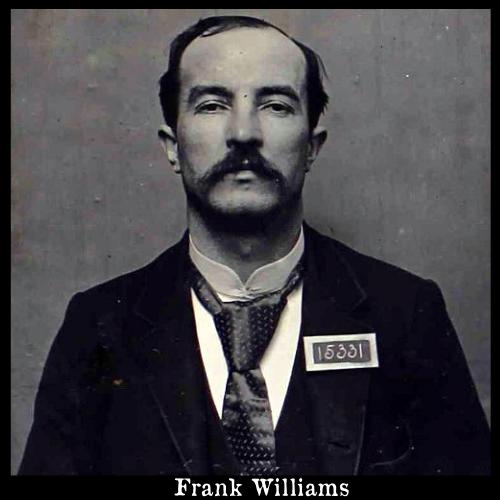

George Sontag had only been in Folsom prison a short time when he began laying plans to escape. He confided his plans to convict Frank Williams, a life termer, who told him that if he (Sontag) could get some one to furnish the weapons to be used in the escape, he (Williams) could have them smuggled into the prison. The friend who Williams believed would smuggle guns in was referred to as “Mr. Johnson,” but as a matter of fact he was William Fredericks, who had just been released after serving a term for robbing the Mariposa stage and was subsequently hanged for murdering Cashier Herrick in the San Francisco Savings Union Bank at Polk and Market Streets while attempting to rob that institution in broad daylight. (For particulars see history of Fredericks.)

It was agreed that Williams should write to “Johnson” requesting him to call on Mrs. Chris Evans, and that Sontag should write to Mrs. Evans, hinting as to the object of “Johnson’s” visit.

The Sontag and Evans gang while at Evans’ home did not refer to their weapons as guns and pistols, but named a pistol “Betsy” and a sawed-off gun “Mr. Ballard.” Sontag prepared a letter which read as follows:

“Dear Mrs. Evans :—A very dear friend of mine named Mr. Johnson will call on you, and it is my wish that you will treat him the same as you would me. I wish you would introduce him to Betsy and Mr. Ballard, as he is a very nice man.

Sincerely yours,

GEORGE SONTAG.”

Sontag and Williams then ingratiated themselves with a clergyman who frequently visited the prison and who was greatly impressed by their outward show of penitence. The good man concluded that it was their environments that led them astray and not their natural inclination. So when this brace of penitents “innocently” asked him to mail two letters, he willingly agreed to do so, as he read them and they appeared “perfectly harmless.” Mrs. Evans refused to assist them.[1]

At 3:30 p. m., June 27, Lieutenant of the Guards Frank Brairre was sitting in a chair near the quarry, when George Sontag approached him. As Sontag belonged in the stonecutters’ shed nearly a quarter of a mile away, the Lieutenant said: “Well, what do you want here?” “Rock,” replied Sontag sententiously.

At that moment, convict Anthony Dalton approached from behind and seizing Brairre said: “We want you.” Convicts Frank Williams, “Buckshot” Smith, Charles Abbott and Hy Wilson then rushed up, and using the Lieutenant as a shield, attempted to escape. Williams ordered Brairre to signal Guard Prigmore, who was in charge of a gatling gun, not to shoot, but the signal was not given in a satisfactory manner, and Williams shot over Brairre’s head, but it is not probable that he intended to kill him for they would then lose their shield and would be riddled with bullets from the numerous guns already trained on them. All these convicts were armed with rifles and knives. They took the guard up the hill and when they came to the brink of a deep gulch, he jumped over, carrying Smith to the bottom with him. They bounded to their feet about the same time, and Smith seized a stone hammer and struck the guard on the head, but after a desperate struggle the guard overpowered him. When the guard jumped over the cliff the gatling guns went to work with deadly effect on Sontag, Williams, Abbott, Dalton and Wilson.

The desperate men then sought refuge behind a big rock, but this did not afford protection from all the guns, and in a few moments Williams, Dalton and Wilson were virtually shot to pieces, and Sontag and Abbott, both dripping with blood from their own wounds, piled up the dead bodies of their fellow prisoners and used them as a shield.

Finally they concluded that there was no possible chance for escape and they gave a signal of surrender by placing a hat on the end of a rifle barrel and waving it in the air.

While this battle was raging, rumors reached the main prison that the convicts had escaped, and the prisoners cheered and yelled like fiends until the wagons drove up, loaded with the dead and dying prisoners. Like magic, a death-like silence came over them when they beheld the gory remains of their associates and realized how completely and tragically the attempt to escape had been frustrated.

It was thought that George Sontag would die from his wounds, but he eventually recovered, although he will be a cripple for life.

A young convict named Thomas Schell, from San Francisco, happened to be within range of the guns when the firing began, and although he did not participate in the attempted jail break, he was killed by a chance bullet.

Dalton was a graduate of Harvard College, but was a criminal at heart and was, at the time of his death, serving a twenty-year sentence for burglarizing Ladd’s gun store in San Francisco. While being taken to Folsom to serve this sentence he escaped temporarily by jumping from the car window while the train was running full speed. Williams was serving a life sentence for robbing stages. He held up twelve stages in five months and held up one stage twice on the same day.

On July 3, 1893, John Sontag died at the Fresno jail from the wounds he received while making his last stand with Evans.

On November 28, 1893, Chris Evans was placed on trial for the murder of Vic Wilson, but before the jury had been empaneled, George Sontag sent for Warden Aull at the Folsom prison and made a full confession of all of his crimes. He stated that he had two reasons for so doing.

First: Because Mrs. Evans had ill-treated his mother when she came to Visalia to nurse John, and had given her none of the proceeds of the Collis robbery; and

Second: Because he was crippled for life while attempting to escape from Folsom, and by assisting the prosecuting officers he hoped to secure their assistance when he applied for a pardon later on.

On December 2, George Sontag was brought from Folsom to Fresno and testified against Chris Evans.

On December 14 the jury, after deliberating seventeen hours, returned a verdict of guilty of murder and fixed the punishment at life imprisonment.

While awaiting sentence Evans was incarcerated at the Fresno jail where his wife visited him daily, and he was also permitted to have a waiter from Stock’s Restaurant bring his meals into the corridor of the jail, where Evans partook of them.

About 6 p. m., December 28, 1893, Mrs. Evans was in the prison with her husband when Morrell, the waiter, called and took Evans’ meal into the corridor of the prison. The prisoner was, as usual, permitted to leave his cell and eat in the corridor in company with his wife and the waiter. When Evans had finished, the waiter called to Ben Scott, the jailer, to let him out with his tray of dishes. When Scott opened the door, the waiter drew a long knife and held it near Scott’s heart and ordered him to hold up his hands. The jailer thought it was a joke, but was convinced to the contrary when Evans whipped out a revolver, which Morrell had smuggled in to him, and pointed it at Scott’s head. Mrs. Evans attempted to grasp the pistol, but Evans pushed her away, and Scott believing that “discretion was the better part of valor,” opened the door and Evans and Morrell walked out.

Before leaving, however, Evans said to Scott: “My wife had nothing to do with this and you take good care of her.” The desperadoes then made Scott accompany them. They next met ex-Mayor S. H. Cole. “Up with your hands,” said Evans to Cole, and proved his earnestness by placing his pistol against Cole’s chest, and he was forced to join the party.

When they reached the Adventist Church, they met City Marshal John Morgan and William Wyatt. Morrell thrust a pistol up to their faces and commanded them to throw up their hands, and although Morgan was acknowledged to be a brave man, he was so taken by surprise that he complied with the request, but when Morrell began searching him, Morgan threw his arms around the robber whom he and Wyatt were rapidly overpowering. Morrell called to Evans, who had remained some little distance away with his involuntary companions, Cole and Scott. Evans left his prisoners, who then fled, and he ran to Morrell’s assistance. He fired two shots into Morgan, who relinquished his hold on Morrell and sank to the ground, seriously wounded, while Wyatt ran for help. Morrell obtained Morgan’s pistol and he and Evans ran to a team which was hitched nearby, but the animals became excited because of the shooting and as soon as untied they ran away, leaving the bandits to make their way on foot.

After traveling a few blocks they seized a horse and cart from a newsboy and escaped.

Although these men were seen several times after their escape, nothing of any moment occurred until February 8, 1894, when a posse came upon them, and although several shots were exchanged, no damage was done and they again escaped.

On February 19, the bandits became so bold as to go to Evans’ home in Visalia, and the information was at once conveyed to the officers, who formed a cordon of fifty men around his house about 3 a. m. The outlaws knew nothing of their predicament until Sheriff Kay sent a boy named George Morris to the house with a note informing them that further resistance would be foolish. It was now daylight and Evans could see that they were trapped. He finally sent his little son out with a note to Sheriff Kay, which read as follows:

“Sheriff Kay :—Come to my house without arms and you will not be harmed. I want to talk to you.

“CHRIS EVANS.”

After an exchange of several notes it was agreed that Sheriff Kay and Will Hall would go into Evans’ yard unarmed, and when they did so Evans and Morrell came out, shook hands with the officers and surrendered unconditionally.

Morrell was charged with robbery for forcibly taking Marshal Morgan’s pistol and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

On February 20, 1894, Evans was sentenced to serve the remainder of his life in State Prison.

After Evans was sent to State Prison, his wife and daughter Eva appeared throughout the State in a melodrama called “Sontag and Evans,” which depicted the bandits as persecuted heroes.

On March 21, 1908, George Sontag was pardoned and obtained employment as a “floor manager” in Tim McGrath’s resort on Pacific Street in San Francisco. He soon left this position and wrote a book dealing with his past life, in which he warns others of the folly of wrongdoing.

[1] In a confession made by Fredericks to Detective Seymour on March 24, 1894, he stated that it was he who furnished all the weapons and ammunition used in the attempted jail break, and that he wrapped them in a blanket and left them in the prison quarry. He stated that he stole two rifles in a saloon in Visalia and bought other weapons and ammunition in Sacramento. Before being released from Folsom he promised to assist several of the convicts to escape, and on the day of their attempt he was stationed at a deserted stamp mill near the prison with clothing to be exchanged by the convicts for their prison garb.