Louis Dabner, John Seimsen, and the San Francisco “Gas-Pipe” Murders of 1906

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part I: San Francisco Cases

Never since the days of the famous Vigilance Committee in 1852-56 were the citizens of San Francisco more terror-stricken by the criminal element than during the five months following the great earthquake and fire in April, 1906.

Because of the vast amount of taxable property destroyed it was decided that all branches of the municipal government must economize, and the police force was temporarily reduced about one-fifth by forcing members to take a leave of absence. The criminal element was quick to take advantage of the situation, and the result was that a series of most atrocious crimes were committed.

Some of our most prominent citizens were beaten and robbed on the Streets, and finally the desperadoes became more bloodthirsty and murdered merchants and bankers in their places of business in broad daylight.

On the night of July 10, 1906, Coroner Leland was assaulted and robbed by two thugs at the corner of Laguna and Vallejo Streets.

Owing to a remarkable chain of circumstantial evidence an ex-convict named James Dowdall was arrested for this crime, partially identified by Dr. Leland, and convicted. He was sentenced to fifty years’ imprisonment.

Johannes Pfitzner was the son of Adolph Pfitzner, the Chief Architect to Emperor William of Germany. The son left home to make his own way in the world, and immediately after the big fire opened a small shoe store at 964 McAllister Street.

On the afternoon of August 20, 1906, he was found on the floor of his store in a dying condition, his head having been crushed in by a window weight, which was found near the body. About $140 and his gold watch was missing. It was evident that he was in the act of trying a pair of No. 8 shoes on some man when the fatal blow was struck.

At 3:10 p. m. on September 14, 1906, a little boy named Robert Anderson and his sister, Thelma, entered the clothing store conducted by William Friede, at 1386 Market Street.

Seeing no one in the front part of the store the children went to the rear, which was Friede’s workshop and where customers tried on clothing. Here they found Friede lying in a pool of blood, his head being battered to a pulp. His tape measure lay beside him, his pockets were turned inside out; his watch, containing a picture of his family, was missing, and the money drawer was empty. The wounded man died the next day without having recovered consciousness.

There was no evidence to show what instrument was used in committing this assault. On the following day Friede’s watch was found on Market Street, near Dolores.

At 12:30 p. m., October 3, 1906, a Japanese named Yazo Kitashima entered the Japanese bank, known as the “Kimmon Ginko,” located at 1588 O’Farrell Street, but failing to receive any response to his calls he proceeded to President M. Munekato‘s office in the rear. Here he found the President, and A. Sasaki, a clerk, lying on the floor, their heads having been beaten almost to a pulp.

Nearby was a piece of one and one-quarter inch gas-pipe about fourteen inches in length and wrapped in a piece of ordinary wrapping paper. It was covered with blood and evidently was the weapon used in committing the assault.

After rendering the bank attaches helpless, the assailants took all the money in sight, about $2,800. Munakato died two hours after the assault, but Sasaki, after months of suffering, finally recovered, but his mind always remained a blank regarding the circumstances leading up to the assault.

Governor Pardee took cognizance of the unprecedented number of atrocious crimes being committed in San Francisco, and on October 12, 1906, he offered a reward of $1,500 for the arrest and conviction of the murderers of Pfitzner, Friede and Munakato.

On Saturday evening, November 3, 1906, three men entered the jewelry store conducted by Henry Behrend, at 1323 Steiner Street, and after making a pretense at purchasing jewelry assaulted him. One man took about $75 from the till, another held Behrend, while the third rained blows on his head with an iron bar.

Behrend resisted and dodged the blows. This caused the man who was holding him to place one hand on the side of his head to hold it still so that the third man’s blows would be effective. The next blow struck one of the fingers of the man who was holding Behrend and almost cut it off. The robbers became alarmed and fled, with the exception of the man who was wielding the iron.

Notwithstanding the fact that Behrend’s face and head were covered with his own blood, he bravely held on to this man until Officers John T. Conlon, William Lambert, James Welch and W. F. Brown, a fireman, appeared and took the assailant into custody. The cry that one of the “gas-pipe” men had been captured spread like wildfire, and the great crowd, which assembled in front of the jewelry store, were continually uttering cries of “Lynch him,” and considerable difficulty was experienced in dispersing the indignant citizens.

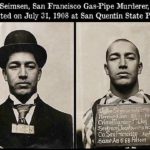

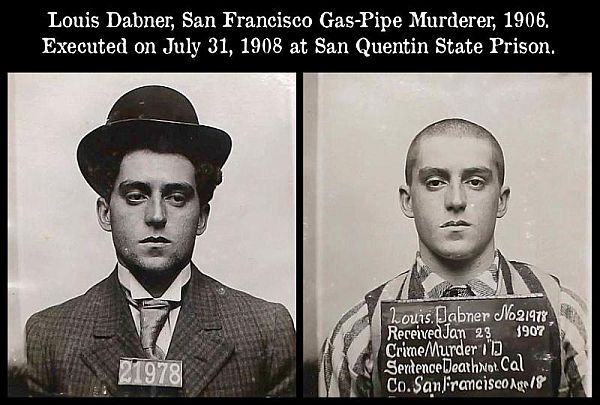

The robber was taken before Chief Dinan and Captain of Detectives Duke. He at first refused to discuss his identity, but upon being told that he would be shown at midnight to every policeman in the city for identification he admitted that his name was Louis Dabner and that he resided at 1786 Union Street. He also admitted that his roommate was John Seimsen, whose father was at one time a very wealthy citizen in Honolulu. Dabner claimed that Seimsen had nothing to do with the assault just committed. Upon making an investigation it was learned that the description of Seimsen tallied with that given by Behrend of the man who held him, and Behrend furthermore stated that the man who held him had a wounded finger.

Some days previous, Seimsen, who had posed as the heir to a vast estate in Honolulu, secretly married Miss Hulda Von Hoffen, whose father conducted a jewelry store on Union Street near Buchanan. Seimsen had an appointment that evening with his wife, who was still living at her father’s home.

Subsequent developments proved that Seimsen was actually the assailant whom Behrend described as having a wounded finger. As it was necessary for Seimsen to explain this injury to his wife, he stated that he had been “held up” and that because his diamond ring could not be readily removed the highwayman attempted to cut his finger off.

His wife telephoned the details of the alleged robbery to her father, against the wishes of Seimsen. Shortly after receiving the message Mr. Von Hoffen met Chief Dinan and Captain Duke, who were fen route to Dabner and Seimsen’s room, and informed them of his daughter’s message.

The officers pretended that they had heard all about the “robbery” of Mr. Seimsen, and stated that they had located the robbers and were looking for Mr. Seimsen to identify them. Mr. Von Hoffen was highly elated, and bade them wait at his door, as his daughter had telephoned that they were on the way home. Presently Seimsen arrived with his wife, and the officers said: “Well, Mr. Seimsen, we have the men who robbed you and we want you to accompany us to the station to identify them.” Seimsen stated that he would call the next day. As he moved his hand toward his hip pocket the officers closed upon him and removed a big pistol from his possession. He then said: “Well, I guess it’s all up,” and confessed to participating in the robbery that night, but denied having taken part in any other crime. He was at once identified by Chief Dinan as an ex-convict who had served four years for stealing some instruments from a Hawaiian musician.

Within a few days the police gathered an abundance of evidence against the pair, even ascertaining where the $2,800 taken from the Japanese bank was spent. Dabner’s father was a highly respected citizen of Petaluma, Cal., and on November 6, 1906, in company with Captain of Detectives Duke and Detective Wren, he visited his son. At this time he demanded proof that his son had committed murder, and the evidence was laid before him. Being convinced of his own son’s guilt he begged him to tell the truth. The boy still professed to be innocent, but when additional evidence was disclosed, he finally weakened and made the following remarkable confession:

Louis Dabner’s Confession:

“On the night of July 10, Seimsen and I held up Coroner Leland at the corner of Vallejo and Laguna Streets. I know it was Dr. Leland because we got papers and checks from his person giving his name. We sent the check, gunmetal watch, chain and Masonic emblem back to him in a pastboard box, by mail. We got the pastboard box at the candy store at the corner of Union and Octavia Streets. I inclosed a note to Dr. Leland in my own handwriting, and wrote the address on the box.

“Seimsen said to Leland : ‘Throw up your hands,’ and pointed a gun at him. Leland attempted to wrestle, and he got hold of the gun. Seimsen held the gun with one hand and used the other to go through him, and I went through him on the other side. We got over a hundred dollars. I am almost sure we took either a five or a one dollar greenback. Seimsen ordered him to walk down the street. Seimsen and I ran across the lot where the refugees built their fires.

“We jumped the fence and went through a private yard and out the front way. We saw a fellow stand and look at us, but we kept running. We left two old black overcoats, three-quarter size, two slouch hats and a few of Leland’s keys in a chicken house back of an empty house on Filbert or Greenwich Street, between Buchanan and Laguna. We stayed ..in the chicken house about half an hour and then went home.

“We were in court as spectators when James Dowdall was convicted for this crime and also when he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

“On the night of August 18, myself, Seimsen and Harry Sutton, an ex-convict, went out on Pacific Avenue and Buchanan Street. We saw a tall, stout man, with sandy mustache, coming east on Pacific Avenue. He had some parcels in his hand. Seimsen jumped out and told him to throw up his hands. Harry Sutton went through one side of him and I went through the other side. Seimsen hit him with a black jack, but the lead flew off and it did not hurt him. We got $5 from him. We each took $1, and drank up the remainder. This man, whom we learned through the papers was J. H. Dockweiler, a civil engineer, ran to a house, rang the bell and yelled ‘Police.’

“One Saturday night in the month of May, Seimsen and I went into E. E. Gillon’s hardware store, on Point Lobos Avenue, on the north side. I pretended to want to purchase a knife. He showed me one and I threw out $20, and he threw back the change. Seimsen then threw the gun up at him and ordered him to throw up his hands and throw up the money and face about. I took $38 of his money. Seimsen then ordered him to the back part of the store. Seimsen watched him awhile and we then walked away. We laid low for a while and then took the car and went home.

“On the day of the Pfitzner murder, Seimsen and I looked in the showcase of the store and went down the street and then came back to the store. Seimsen tried on a pair of shoes the first time, but complained that they were too dear, and we went out. We walked around the block and came back. We both went in the store and I tried on a pair. When he was trying on my shoes Seimsen hit Pfitzner on the head with a window weight and he fell to the floor. I then put on my own shoes and held the door at the same time, while Seimsen went through Pfitzner. Seimsen got about $100, which we divided at our home on Union Street. We threw Pfitzner’s watch in the water at the foot of Fillmore Street.

“Seimsen and I passed Friede’s place on Market Street the day of the murder. At this time there was a ‘run’ on the Hibernia Bank, so we watched the depositors leaving, intending to follow up any one who looked to be worth the while, but not seeing anything that looked ‘good’ we passed back by Friede’s. We were looking into the store, and Seim-sen said he thought this was an easy place. We went in and Seimsen told me to try on a suit. Friede was measuring me for a pair of pants when Seimsen hit him on the head and knocked him unconscious with a gaspipe that I picked up. Seimsen then went through his pockets and I went through the till. I took all the money I found in the till, which I divided with Seimsen at our home on Union Street, where we went immediately after the assault.

“Immediately after we killed Friede in the back part of his store a customer came in the front part, and fearing that he would come to the rear and discover our deed, I pulled the shop tag off the new coat which I then had on, took off my hat, and pretending to be a clerk, walked out behind the counter and asked him what he wanted. He said he wanted some ‘canvas for lining.’ I informed him that I was a new clerk and was not familiar with the stock, and asked him to please call later, which he agreed to.

“Friede’s money was evidently in an old-fashioned money drawer which slid under the counter and could only be opened by someone having a knowledge of the combination under the drawer which were manipulated with the fingers.

“I realized that if I pressed the wrong keys and attempted to open the drawer the bell would ring, which would probably be heard in the next store, as it was only a temporary building with thin board partitions, and we were forced to operate very quietly. I reasoned that Friede, being familiar with the combination and using it many times a day would press only on the proper key, and that the key would show the effects of constant usage, whereas the others would probably be dusty. I therefore lit a match and getting under the counter it was apparent at a glance which keys of the combination had been used, so I pressed them and the drawer containing the money flew open.

“On the morning of the Japanese bank robbery, Seimsen and I left home together. We had planned the day before to rob the Japanese bank on the following day at noon. Seimsen went into the bank on the day previous to the murder. When he came out he told me that he had represented himself to be a man of business and that he intended to deposit money there.

“On the day of the robbery we hung around the bank for a while, and after we saw the clerks go away to lunch we went in. Seimsen stepped in front and told the Japanese in the front part that he wanted to see the manager. Then Seimsen and I went back to the manager’s office. Seimsen saw the manager was writing, and as the other Jap was not looking, he (Seimsen) hit the manager over the head with a gaspipe which I got at Convey’s store on Union Street, near our house, and which I wrapped in a piece of paper I got in the same store. I got this pipe the night before the assault.

“After Seimsen knocked the manager out I called the other Jap back to the rear office, according to our original plan. When he came back, Seimsen hit him over the head several times and he fell.

“The Jap who was called from the front started to get up, and I hit him myself with the pipe on the head, and he fell again. Seimsen then went through the till and we got about $2,800, partly in silver and partly in gold, which we put in a satchel. Not being able to find anything else but checks we left.

“We then went to Seimsen’s horse and buggy, which we left standing on Webster Street, between O’Farrell and Geary, and drove to Van Ness Avenue, where we met Seimsen’s wife.

“We separated, as he said he was going to take his wife out for a drive. I then took one of the Von Hoffen children in my buggy out to the Presidio, and I brought her home in about two hours.

“During the time I had the Von Hoffen child out riding and until 7 o’clock that night I left the satchel containing the money in a sack of oats where we kept our rig. About 7 p. m. I came and got the satchel containing the money and took it to the room occupied by myself and Seimsen. We counted it that evening and left it in our closet. On this evening I took the horse and rig to Conlan’s stable, on Greenwich Street, near Laguna, and stabled it there. It was a sorrel horse with a white face and legs, and the buggy is now at Worst’s paint store.

“Seimsen and I spent $246 of the silver which we took from the Japanese bank at .Macey’s Jewelry Company, 1700 Fillmore Street. We also spent about $200 in silver at Paul Garen’s jewelry store, 1558 Fillmore Street. We spent $165 at the Hub clothing store, on Fillmore Street. At Heller’s, on Van Ness Avenue, Seimsen spent $95 and I spent $50. Seim-sen also spent $75 at Alexandra’s, on Van Ness Avenue, near Sutter Street. Seimsen spent $150 at Alexandra’s for a locket, watch and diamond engagement ring for his wife. All of the money above mentioned was taken from the Japanese bank.

“This and all statements and confessions made by me this date (November 6, 1906), to Captain Duke, in the presence of my father, are free and voluntary and without threats or promise of reward.

“(Signed) LOUIS DABNER.”

Seimsen, on being confronted by Dabner after the confession, at first denied that the statements were true, but he finally weakened and admitted that it was the truth and signed his name to it. Seimsen then explained how Friede’s watch was found at Market and Dolores Streets.

He stated that Dabner and he boarded a Market Street car immediately after the assault and stood on the rear end. When they reached Dolores Street he noticed a watch hanging to a button on his vest. He opened it, and seeing that it contained a picture of a group consisting of his latest victim, a lady and baby, he concluded that the ring of the watch became caught on the button in, some inexplicable manner while searching the body. He then threw it into the street.

Detective Gus Harper was immediately detailed to substantiate the confession in relation to the robbery of Dr. Leland, and as it was proved beyond all doubt that the confession was true, the matter was laid before Governor Pardee, who granted a pardon to Dowdall.

Seimsen and Dabner were tried for the murder of Munakato. Dabner pleaded guilty. Seimsen pleaded not guilty, but the jury lost no time in finding him guilty, as every statement in the confession was proved to be true. Both were sentenced to be hanged, but an appeal was taken to the Supreme Court, which handed down a decision on April 27, 1908, in which the rulings of the lower court were affirmed.

On July 31, 1908, both men were hanged from the same scaffold at San Quentin. Dabner’s father died shortly before the execution, and Pfitzner’s father died soon after hearing of his son’s tragic death.

It was learned that the third man in the Behrend robbery was Harry Kearney from Sacramento, who is now in prison in Washington for a similar offense.

Dowdall has since been returned to State prison for committing a burglary.

—###—