The Chicago Car Barn Bandits and Murderers, 1903

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part III: Cases East of The Pacific Coast

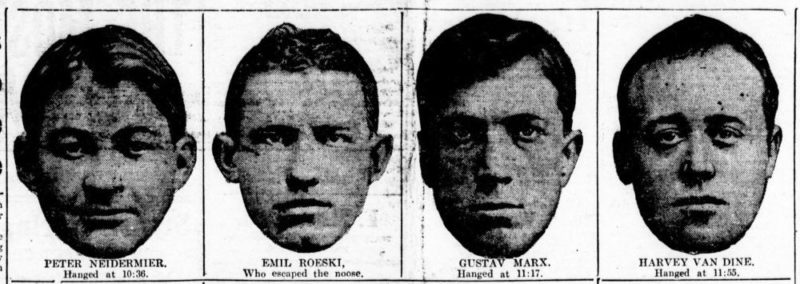

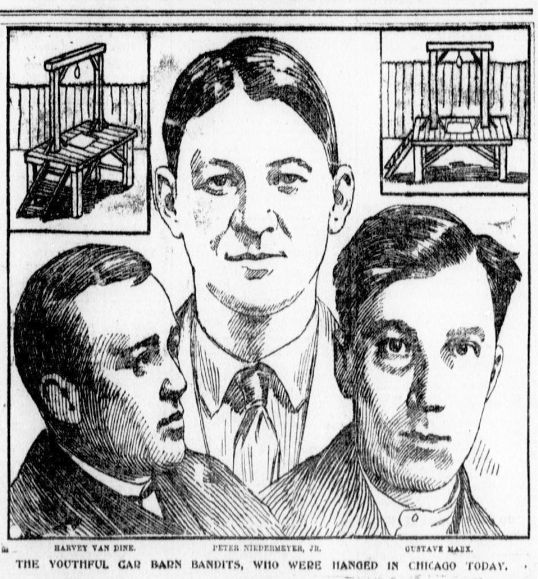

During the months of July and August, 1903, a reign of terror prevailed in Chicago similar to that which prevailed in San Francisco shortly after the great earthquake when Seimsen and Dabner, the “gas pipe” thugs, were plying their vocation. The gang responsible for this condition consisted of four very young men named Gustave Marx, Harvey Van Dine, Peter Neidemeyer and Emil Roeski.

While this gang consisted of four members, there was no instance where less than two or more than three participated in any one crime.

Their criminal career began in 1901, when Neidemeyer, Van Dine and Marx stole some lead pipe from the Audubon School in Chicago, for which they were sent to the “Bridewell” jail for three months.

On the night of July 3, 1903, Neidemeyer and Roeski held up L. W. Lathrop and Martin Doherty while they were engaged in their duties at the Clybourn Junction station of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad in Chicago. Lathrop offered resistance and was shot, but not fatally wounded. After obtaining $70 the bandits escaped.

On July 9, Marx, Van Dine and Roeski held up the saloon conducted by Ernest Spires at 1820 North Ashland Avenue. Roeski went into the saloon and ordered a glass of beer. At that time the proprietor and a young man named Otto Bauder were the only other persons in the place. Van Dine and Marx then entered and ordered them to throw up their hands. Bauder tried to escape but Roeski shot him in the back, inflicting a fatal wound. Less than $50 was taken from the proprietor and the bandits departed.

On the following night, Van Dine and Roeski entered Greenberg’s saloon at Robey and Addison Streets, and after forcing the bartender, Louis Cohen, who was the only one in the saloon, into the large ice chest, they took $25 from the cash register and disappeared.

On the night of July 12, the same pair entered Charles Alvin’s saloon at Sheffield Avenue and Roscoe Street, and after drawing their automatic revolvers, which they habitually displayed on such occasions, ordered the proprietor and four patrons to hold up their hands while one of the robbers searched them. About $125 was obtained and again the pair escaped.

On July 20, the same two entered Peter Gorski’s saloon, located at 2611 Milwaukee Avenue. The proprietor, who was alone at the time of their entry, attempted to hide behind the bar, but was shot in the head, a serious but not fatal wound being inflicted. The robbers obtained less than $5 from the cash register and fled.

On the night of August 1, Van Dine and Neidemeyer entered the saloon conducted by Benjamin La Cross, located at 2120 West North Avenue, where the proprietor and Adolph Jennsen were playing a game of cards. Without the slightest provocation the blood-thirsty bandits opened fire, inflicting wounds from which both men died within twenty-four hours. Sixty-four dollars was obtained on this occasion.

About 3 a. m. on August 30, 1903, Marx, Van Dine and Neidemeyer approached the car barn of the Chicago Street Railroad Company at Sixty-first and State Streets. In the office of the company, William Edmund, Frank Stewart and Henry Biehl were engaged in balancing up the day’s receipts, and J. Johnson, a motorman, was asleep in a chair in an adjoining room. Neidemeyer stopped at a side window of the office where he could observe all that transpired inside, while Marx and Van Dine, who carried a sledge hammer, proceeded to the entrance. The former pointed his automatic revolver through the receiving window at the occupants of the office and commanded them to throw up their hands, while Van Dine broke in the door with his sledge hammer, which was left in the office.

As the clerks attempted to defend the company’s money, a fusillade of bullets was fired, both from the bandits in the office and from Neidemeyer, who fired through the window from the outside. On hearing the shots, motorman Johnson came into the room, the final result of the firing being that Stewart and Johnson were killed and Edmund and Biehl were seriously wounded. The bandits then gathered $2,250 and went to Jackson Park, where the money was divided.

In the early part of November, 1903, Assistant Chief Schuettler learned that Marx was a frequenter of numerous resorts on the west side, and although out of employment, he was spending money recklessly. It was also ascertained that while under the influence of liquor he exhibited an automatic revolver. Detectives John Quinn and William Blaul of the 42nd Precinct were detailed to locate and arrest this fellow.

On the night of November 21, 1903, he was located in Greenberg’s saloon, the same place which Van Dine and Roeski held up on July 10. It was arranged that Blaul should enter the side door at the same instant Quinn entered the front door of the saloon. Marx saw them as they entered, and like a flash he fired at Quinn, killing him instantly. Blaul fired and slightly wounded Marx. The officer then leaped forward and overpowered the bandit before he had an opportunity to fire again. Marx was manacled and taken to jail, where Assistant Chief Schuettler subjected him to a severe examination. At first the thug was non-committal, but when he realized that he would probably hang for the murder of Quinn and believing that his companions had deserted him, he finally made a complete confession of the crimes committed by the gang, as heretofore related in this narrative.

In addition, it was learned that the sledge hammer used in the car barn robbery, which had a letter “N” burned in the handle, was stolen by Van Dine from the Northwestern railroad shops, where he was formerly employed.

Shortly after the confession was made, it became public property and the pictures of the missing bandits were obtained by the police and published in the papers.

Van Dine, Roeski and Neidemeyer then boarded a train and rode out into Indiana, where they took refuge in an abandoned cellar over which a house once stood. After spending a day and night in this cellar they proceeded to a country store conducted by Julius Scheurer at Clarks Station, on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, to replenish their supply of provisions. At this store was a school-teacher named Henry Reichers, who had seen the newspaper pictures of the bandits, and immediately recognized this trio as the men wanted by the authorities. This information was at once conveyed to the Chicago police, and Assistant Chief Schuettler detailed a posse, consisting of Detectives Joseph Driscoll, Mat. Zimmer and six others, to repair to the scene.

That night the officers located the abandoned cellar, but the bandits had fled. As it was dark the officers decided to rest until daylight at John Haynes’ farmhouse, when they again took up the trail, which they had no difficulty in following through the snow. It led them to an old dugout made by railroad laborers near Miller Station.

The officers formed a semi-circle around the cave and called out to the bandits to surrender, but instead of doing so, Neidemeyer and Van Dine stuck their heads out of the hole and began a deadly fire with their automatic revolvers, Driscoll being mortally wounded and Zimmer receiving two serious wounds. As the detectives were entirely exposed to these expert shots, they were forced to retreat.

At this moment, the bandits rushed out of the cave, firing as they ran; Neidemeyer and Roeski being wounded as they fled. They had only traveled a short distance when Roeski became exhausted and, leaving his companions, he cut across a field.

Van Dine and Neidemeyer then ran along the railroad track to a little station, where a locomotive was coupled to some cars. They climbed into the cab, where they found Engineer Coffey and Brakeman L. Scovia. With a display of revolvers, the bandits commanded them to uncouple the locomotive from the train and carry them down the track as fast as possible. Scovia attempted to grapple with Neidemeyer, who shot him in the head, killing him instantly. Seeing the folly of resisting, the engineer promptly obeyed their commands.

In the meantime the movements of the desperadoes had been telegraphed to all the way stations for miles around, and rapidly formed posses were prepared to give them a warm reception.

The locomotive bearing these bandits had only traveled a few miles when a locked switch compelled them to stop and return over the same track. When they had gone back a short distance they ordered Coffey to stop, and after admonishing him to render no assistance to their pursuers under pain of death, they started across the country.

A party of hunters, upon learning of what had transpired, took up the trail and chased the thugs into some marsh land. When the desperate pair saw that they could proceed no further, they turned and had about decided to fight to the end when the contents of a shotgun poured into Van Dine’s face, blinded him with his own blood, and he proposed to Neidemeyer that they surrender. The latter acquiesced and the pair then informed the hunters of their decision, and after throwing up their hands, walked out to their captors.

In the meantime, Chief O’Neil sent out heavy reinforcements in command of Assistant Chief Schuettler, who divided his men into squads and dispatched them in different directions. It was to one of these squads that the bandits were delivered by the hunters.

When Roeski left his two companions, he went to a railroad station named Aetna. His bravado having completely deserted him, he threw his pistol away and lay down on a bench in the station, where the officers finally located him and he surrendered without a struggle.

When Roeski left his two companions, he went to a railroad station named Aetna. His bravado having completely deserted him, he threw his pistol away and lay down on a bench in the station, where the officers finally located him and he surrendered without a struggle.

No effort was made by the Governor of Indiana to enforce the extradition laws and the trio were immediately taken back to Chicago, where they freely discussed their crimes, thereby corroborating the confession previously made by Marx.

The grand jury found indictments against the four men for their numerous crimes, and in the early part of January, 1904, Van Dine, Neidemeyer and Marx were tried for the car barn murders. They were found guilty and hanged on April 22, 1904.

On April 19 Neidemeyer attempted to commit suicide by severing the arteries in his arm with a lead pencil and swallowing the sulphurated ends of a quantity of matches. On the morning of the executions, his helpless condition made it necessary for the officials to carry him to the scaffold in a chair.

As Roeski did not participate in the car barn tragedy, he was tried for the murder of Otto Bauder during the saloon holdup on July 9, 1903. He was found guilty, but as some of the jurors had some doubt as to which bandit fired the fatal shot, he was sentenced to serve the remainder of his life at Joliet prison.

—###—