The Savage Murder of a Sacramento Grocer and his Wife by Russian Refugees, 1894

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part II: Pacific Coast Cases

F. H. L. Weber crossed the plains in 1858, and for thirty years prior to his death he conducted a grocery business on L Street, near the Capitol, in Sacramento; residing with his wife on the floor over his store.

On December 29, 1894, at 9:30 p. m., A. A. Jost, a partner in the business, bade Weber “good-night” and left for his home.

At 11 p. m. two neighbors saw Weber moving about his rooms with a candle in his hand.

Shortly afterward they heard the exclamation “Oh!” which was immediately followed by a noise similar to one piece of steel striking another, but as they attached no importance to what they had seen and heard, they gave the incident no further thought at the time.

On the following morning, Mr. Weber’s son, Luther, who opened his father’s store, was startled when he observed a pool of blood on the floor of the store, and on looking up saw that the ceiling was saturated with the crimson fluid.

He rushed up the back stairs and there a gory spectacle was presented to his view.

On the kitchen floor, he found his father’s body with the head cleft wide-open; his brains having oozed out on to the floor, and in the doorway of the same room lay his mother’s body, butchered in the same frightful manner.

The sight paralyzed the son for a moment, but when he realized what had happened, he fled screaming from the building.

It was evident that Weber Sr., had heard some unusual noise and was in the act of investigating when his neighbors saw him with a candle. When he was attacked in the kitchen his wife evidently started to his assistance when she was also assaulted.

The assassins then ransacked the entire house, and in addition to taking two suits of clothing belonging to Weber, they stole two watches, $200.00, a revolver and some underwear.

An ax belonging to Weber was found covered with blood in the back yard, and on further search, some rough clothes covered with blood were also discovered.

It was concluded that at least two men were implicated in the murder and that they wore Weber’s clothing in lieu of their own blood-soaked garments.

On New Year’s Eve, the usual round-up of drunks occurred in San Francisco, and as a result the cells at the old California-Street station were crowded.

On the following morning, according to custom, the bleary-eyed and foul-smelling drunks were placed in a line, and after solemnly swearing off for the remainder of the year they were released, after being reprimanded by the judge.

The work of scrubbing out the cells then began, and a small gold watch was found behind a toilet in one of the cells.

It was sent to Captain I.W. Lees for investigation, and from a description already received, he instantly recognized it as one of the watches taken from Weber’s house on the night of the murders.

Luther Weber immediately came to San Francisco and identified the watch as one presented to his father.

In August 1893, (sixteen months before Weber and his wife were killed) ten prisoners, who were confined in the Russian penal settlements on Sakhalin Island, made their escape, and after enduring almost indescribable hardships, finally reached the eastern coast of the island. After procuring an open boat they put to sea, where their sufferings from exposure, thirst and hunger were about to drive them insane, when they were picked up by the American Bark Chas. W. Morgan, bound for San Francisco.

In August 1893, (sixteen months before Weber and his wife were killed) ten prisoners, who were confined in the Russian penal settlements on Sakhalin Island, made their escape, and after enduring almost indescribable hardships, finally reached the eastern coast of the island. After procuring an open boat they put to sea, where their sufferings from exposure, thirst and hunger were about to drive them insane, when they were picked up by the American Bark Chas. W. Morgan, bound for San Francisco.

When they arrived in San Francisco they claimed that they were thrown into the Russian prison merely because of their political beliefs. The newspapers published lengthy interviews, in which the Russians described at length the suffering they had endured, and the good people of the city, believing them to be poor, persecuted creatures, showered them with kindness.

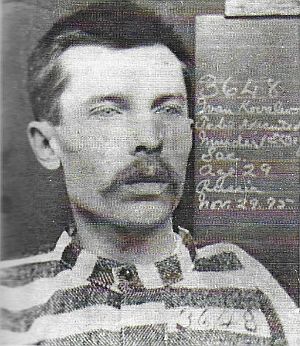

Among these refugees were John Koboloff, alias Ivan Kovalov, and two others, named Nikitin and Stcherbakov.

On June 12, 1895, Deputy Sheriff Martin Hughes informed Captain of Detectives Lee that he believed that a man named E. K. Bennett, of 937 Post Street, could impart some valuable information regarding the Weber murder case.

Lees sent for Bennett, but all he knew was that a man named L. Stevens, residing at 715 Howard Street, was supposed to know something concerning the crime.

Stevens was brought forth, and he stated that he had become acquainted with a ship carpenter named Vladislav Zakrewski, who had gained the confidence of Kovalov, one of the Russian refugees.

Zakrewski told Stevens that he could put his finger on the murderer of the Webers, and after swearing Stevens to secrecy, stated that Kovalov was not only the murderer but that he still had some of Weber’s belongings in his possession.

Detective Chas. Cody and Officer Tom Tobin (now lieutenant) located Zakrewski in a shack on the Seventh-Street dumps. He stated that one night Kovalev visited him and they spent the evening drinking. Finally Kovalev became intoxicated and, in a burst of confidence, related to Zakrewski how he and another Russian refugee named Matthiew Stcher-bakov murdered the Webers. Zakrewski then accompanied the officers to Kovalev’s room at the St. David house, on Howard near Fourth Street, where Kovalev and one Arnold Levin were found in bed.

Both men were taken into custody and all of their effects were removed to Captain Lees’ office.

The daughter of the murdered couple came from Sacramento and she positively identified a pair of suspenders found in the possession of Kovalev as the property of her father, and pointed to some fancy needle-work she had done on them.

The incident in relation to the watch found in the prison was again a subject for investigation.

It was ascertained that Kovalev was arrested on New Year’s Eve, while engaged in a drunken brawl with a young man named Geo. Petelon, in a saloon at Clay and Kearny Streets.

On June 25, 1895, Petelon was located, and upon being brought before Kovalev, immediately identified him as the man with whom he was arrested and sent to the California-Street station.

He furthermore stated that although Kovalev could speak the English language well enough to be understood, he could not read it, and on New Year’s Eve, when they first met, the prisoner purchased an evening paper and asked Petelon to read to him all it contained in regard to the developments in the Weber murder case.

On the night of March 31, 1895, William Dowdigan was en route from his grocery store to his residence, in San Jose, when he was attacked by three men. Dowdigan had a jackknife in his hand and he stabbed one of his assailants in the side, whereupon all three fled. Dowdigan reported the occurrence to the police, who placed little credence in the story, but the next day the body of a man, which answered the general description of one of the holdup men, was found near the scene of the assault.

In addition to the wound in the side, the man had also been stabbed through the heart.

Zakrewski informed Captain Lees that he accompanied Kovalev, Stcherbakov and Nikitin to San Jose for the purpose of committing a series of robberies, but that he changed his mind and refused to participate in any crime. Kovalev afterward confessed to him that the remainder of the party held up Dowdigan and as Stcherbakov was so seriously wounded by the grocer that they would have to leave him behind, it was feared that he would fall into the hands of the police and tell all he knew, so Kovalev stabbed his companion through the heart for the purpose of sealing his lips.

On June 27, the authorities proceeded to the potter’s field in San Jose and dug up the body of the highwayman. Although terribly decomposed, enough remained intact to convince the officers that it was the remains of Stcherbakov.

Levin, who was arrested with Kovalev, confessed that he accompanied Stcherbakov and Kovalev to Sacramento, but when they requested him to aid them in the commission of several burglaries, he refused and returned to San Francisco. He furthermore said:

“I saw them again in San Francisco on January 5, and they were both well dressed and Kovalev wore a gold watch and chain.

“Kovalev was extremely nervous and when I questioned him as to the cause, he began crying and expressed the fear that he would be hanged, but would not state what crime he had committed to justify such punishment.

“On another occasion, Kovalev informed me that he was implicated in the murder of a large family in Russia and that was the true cause of his confinement in the Russian prison.”

On June 28, 1895, Kovalev was surrendered to the Sacramento authorities, and on July 3 he was held to answer before the Superior Court.

On November 4 his trial began, but was continued for the purpose of examining into the prisoner’s sanity.

He was declared to be of sound mind and the trial proceeded. After the prisoner saw the amount of evidence which had been introduced against him, he took the stand and admitted he was present at the murder, but stated that Stcherbakov struck the blows with the ax.

Kovalev expressed a desire to be hanged as soon as possible, as he felt that he would go insane from the mental torture he was enduring.

When the case was submitted to the jury, on November 30, Kovalev was found guilty of murder with the death penalty attached. On February 21, 1896, he was hanged.

By virtue of the authority found in Section 1547 of the Penal Code, the Governor offered a reward of one thousand dollars for the apprehension and conviction of the murderers.

Captain Lees claimed this reward, but payment was refused by Controller Colgan on the grounds that Lees was a public officer working for a fixed compensation and that he merely performed his sworn duty.

The matter was taken before Superior Judge Troutt, who decided in favor of Lees.

The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court, and on March 11, 1898, that Court handed down a decision upholding Colgan’s contention.

—###—